Juvenile Justice

I studied the juvenile system and family therapy at Western Oregon State College (now WOU), copleting my Master of Science degree in 1991. My research is presented here, including my thesis.*

My degree is in Interdisciplinary Studies, which was a combination of Psychology (Psych.), Criminal Justice (CJ), and Clinical Child and Youth Work (CCYW).

Differential Treatment of Females in the Juvenile Justice System

Psych. 592, Psychology of Women, Winter Quarter, 1990.

Analysis of [Juvenile Correctional Facility]

This is my journal of my internship working in the sex offender ward at a local juvenile reform school.

The Impact of Family Violence on Shaping Delinquent Behavior

Psych 464G, Psychology of Adolescence, Spring Quarter, 1990.

Legal and Social Implications of Childhood Abuse and Delinquency

CJ 451G, Juvenile Delinquency, Spring Quarter, 1990.

Research Article Critique

Term paper, graduate statistics class.

ISKCON as an Addictive Organization

CCYW 578, Drug and Alcohol Treatment, Winter Quarter, 1990 (updated and posted at my website, Surrealist.org).

Lost Essays

These were written and graded, but do not exist in electronic format.

Helping Severely Emotionally Disturbed Adolescents Through a Day Treatment Program, CJ 563, Juvenile Issues, Winter Quarter, 1991.

Juvenile Delinquency: Can Art Therapy Help? CJ 563, Juvenile Issues, Winter Quarter, 1991.

Term Project: One Student's Analysis and Journal, CJ 555, Correctional Casework and Counseling, Fall Quarter, 1990.

Compare and Contrast: Two Parent Training Methods, CCYW 562, Family Work in Child and Youth Services, Fall Quarter, 1990.

Treating an Aggressive Child With a Medical/Behavioral Model Compared to a Systemic Approach, CCYW 576.

Aggressive and Self-Destructive Behavior in Children and Youth, Fall Quarter, 1990.

Abstract - Reaction - Application: Seven Chapters from Mirkin & Koman, CCYW 562, Family Work in Child and Youth Services, Fall Quarter, 1990.

Group Therapy: Sorting Fact from Fiction, Psych. 450G, Abnormal Psychology, Summer Quarter, 1990.

A Developmental Explanation of Social Anxiety, Psych. 460G, Advanced Developmental Psychology, Summer Quarter, 1990.

Toward a Ritual of Divorce, CCYW 587, Contemporary Issues in Family Therapy, Spring Quarter, 1990.

Ethical and Professional Considerations in the Field of Juvenile Delinquency, CJ 451G, Juvenile Delinquency, Spring Quarter, 1990.

Case Study of a Remarried Family, CCYW 587, Contemporary Issues in Family Therapy, Spring Quarter, 1990.

A Fourth Generation German American on German American Family Life, CCYW 587, Contemporary Issues in Family Therapy, Spring Quarter, 1990.

Comparison of Ivan Boszormenyi-Nagy's Contextual Therapy With Jay Haley's Strategic Therapy, CCYW 585, Theories and Methods of Family Therapy, Winter Quarter, 1990.

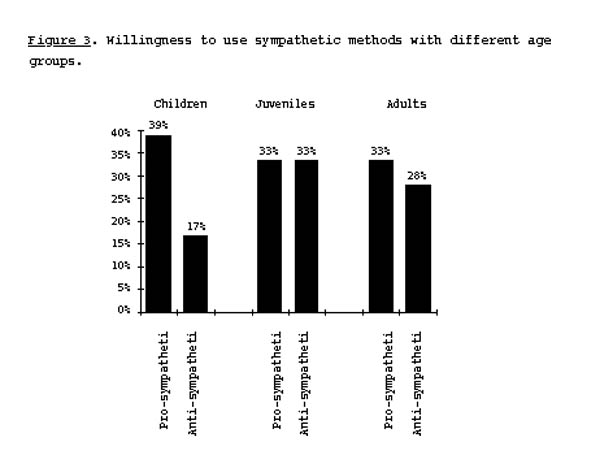

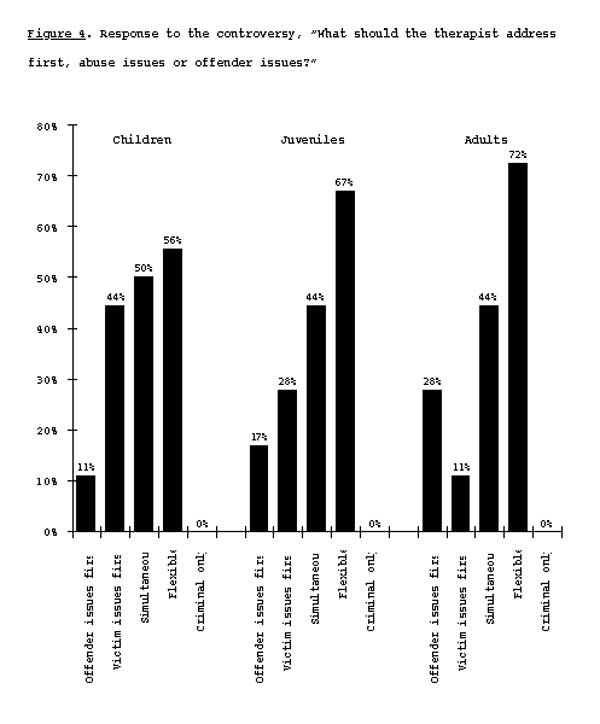

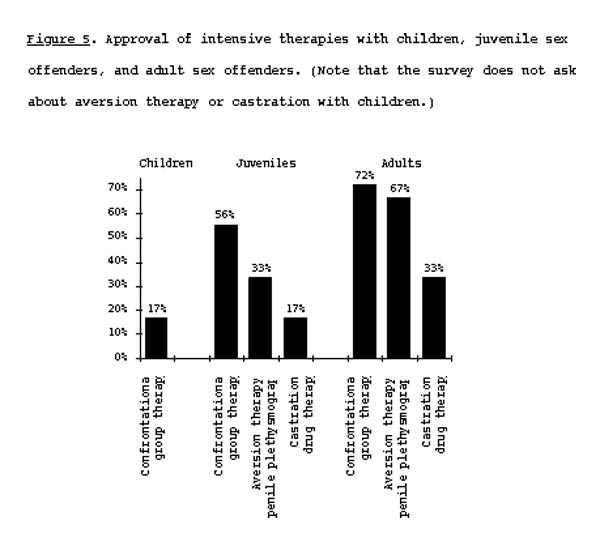

My thesis outlines an art therapy-based treatment plan for juvenile sex offenders. Then it analyzes data I collected from a sample of counselors who stated in their telephone book ads they treated sex abuse victims or sex offenders. I asked the counselors whether they would use art therapy to treat child abuse victims, juvenile victims-turned-offenders, or adult sex offenders.

Graduate students are welcome to replicate my study, but if you use my materials or quote from my thesis, I ask that you acknowledge my contribution to your work. Please cite me as follows in your references: "Nori Muster, author of A Four-Phase Treatment Design for Juvenile Sex Offenders, Western Oregon University, 1991, norimuster.com."

In the years since I did this study, much more has come to light about child abuse. Although I advocate informed art therapy for children and juveniles, fixated pedophiles over the age of eighteen are pretty certainly incurable. If a fixated pedophile forgives himself, or thinks all he has to do is draw pictures, healing is stopped. Before a perpetrator can forgive himself, he must acknowledge the pain he caused his victims and change. Therefore, fixated pedophiles are not at a stage where art therapy can help them. That's why I only worked with juveniles. I believe juvenile sex offenders have their last chance to redeem themselves before they reach the age of majority.

Abstract, Table of Contents

Introduction, Hypothesis, Treatment Design

Statistics - Attitudes Toward Art Therapy

Conclusions, Back Matter

Examples of Juvenile Sex Offender Art Therapy

Treating the Adolescent Victim-Turned-Offender

Article based on my thesis; published in the quarterly academic journal, Adolescence, Vol. 27, No. 106, Summer 1992.

These are the classes I took at Western Oregon University, Marylhurst University Extension, and UCLA Extension Writer's Program. Back then, WOU was known as WOSC, Western Oregon State College. Marylhurst University was known as Marylhurst College.

Western Oregon University

Master of Science degree in Interdisciplinary Studies

1989-1991, GPA 4.0

CRIMINAL JUSTICE 451g Juvenile Delinquency Social dimensions of juvenile delinquency, its nature, demographic distribution, comparison and analysis of agencies, police, courts, individuals, groups, and community efforts in their respective roles of treatment, control, and prevention.

CRIMINAL JUSTICE 506 Special Individual Studies - volunteer work-study at a local youth correctional facility.

CRIMINAL JUSTICE 555 Correctional Casework and Counseling - History, development and contemporary practices, theories and techniques of juvenile and adult correctional casework, counseling and treatment.

CRIMINAL JUSTICE 563 Juvenile Issues - Topics include trends in juvenile, family, school, social agencies, and the court.

EDUCATION 512 Statistics - Methods, techniques, and tools of research. Development of a proposal for a study, and development of the criteria and methods for reading and evaluating research.

PSYCHOLOGY 450g Abnormal Psychology - The nature, causes, and treatment of various forms of unusual behavior and emotional disturbance. The full range of abnormality as defined in the Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association. Course will integrate perspectives generated from psychological theory, research, and physiological findings.

PSYCHOLOGY 460g Advanced Developmental Psychology - Theories of human development across the lifespan, including a review of related research findings and consideration of practical applications.

PSYCHOLOGY 464g Psychology of Adolescence - Transitions and issues of adolescence, including an overview of theory and research with an emphasis on applications for parents, teachers, and professionals offering services to adolescents and youth.

PSYCHOLOGY 592 Psychology of Women - Psychological methods to the study of women's roles and behavior. Sub-topics include development, sexuality, achievement, aptitudes, and work.

CLINICAL CHILD AND YOUTH WORK 562m Family Work for Child and Youth - Approaches to treatment with families of troubled children and youth, such as systemic methods, parent training, filial therapy, and education and support groups. Covers cognitive understanding and skill acquisition.

CLINICAL CHILD AND YOUTH WORK 576m Aggressive and Self-Destructive Behavior in Children and Youth - Theories and methods of understanding, managing, and treating aggressive and self-destructive behavior in children and youth. Topic include theories of childhood aggression, methods of aggression management, social and legal implications of isolation and restraint, theories of suicide and self-destructive behavior, suicide prevention and crisis intervention.

CLINICAL CHILD AND YOUTH WORK 578 Child and Youth Drug and Alcohol Treatment - Research and theoretical explanations for alcohol and drug abuse in children and youth. Topics include individual, family, and peer involvement in substance abuse; treatment modalities and strategies.

CLINICAL CHILD AND YOUTH WORK 585 Theories and Methods of Family Therapy - Current theories of family treatment and their methods: Structural Strategic, Communications, Multi-Generational. Also, innovative methods of family treatment, genogram construction, multiple family groups, networking, video tape playback.

CLINICAL CHILD AND YOUTH WORK 587 Contemporary Issues in Family Therapy - Topics include divorce, step-parenting, blended families, ethnicity, single-parent families, dual paycheck families.

CLINICAL CHILD AND YOUTH WORK 503 Thesis - Develop and write master's thesis under committee chair's supervision.

Marylhurst University

1990-1991

ART THERAPY 016 Introduction to Family Art Therapy - workshop on relevant uses of art therapy in family work.

ART THERAPY 050 Adult Survivor's of Incest - workshop to learn art therapy techniques for survivors.

ART THERAPY 077 Introduction to Dream Workshop - art therapy and dream work.

ART THERAPY Art Therapy and the 12 Steps - art therapy in conjunction with 12 steps.

ART THERAPY 091 Form as Content - Gestalt art therapy workshop with Janie Rhyne.

ART THERAPY 093 Introduction to Art Therapy Workshop - workshop to learn basic art therapy techniques.

PRH 042 PRH: Who Am I? - writing workshop based on the PRH, Personality and Human Relationships, method.

SPIRITUALITY 075 Creation Spirituality - workshop on the just-published (now classic) book, Creation Spirituality, by Rev. Dr. Matthew Fox.

University Extension Writers Program, UCLA

1988-1993

ENGLISH 451.4 - Autobiography into Fiction - writers workshop with Laura Olsher

ENGLISH 404.6 - Tapping Universal Sources - fiction writing workshop

ENGLISH 859.4 - Writers Frame of Mind - writing workshop with a focus on the psychology of writing

ENGLISH 806.19 - Writing as Healing - one-day workshop on creative art therapy

ENGLISH 404.13b - Spirit and Soul Writing Retreat - one week writers retreat with author Elizabeth Upton

ENGLISH 845.2 - First Novel: Planning, Beginning, and Writing - writer's fiction writing workshop

ART 822.6 - Dreamscapes: Drawing from Dreams - art workshop with artist Linda Jacobson

ART 823.1 - The Spiritual in Art Workshop - artist workshop with Linda Jacobson

Following are my Western Oregon University essays that survived; my thesis from WOU is also posted at this site.*

Differential Treatment of Females in the Juvenile Justice System

Juvenile Crimes

The juvenile justice system is meant to reform misbehaved children and keep them from becoming adult criminals. That's why juveniles can be arrested and tried for statutes that don't apply to adults (Shelden, Horvath, & Tracy, 1989). These crimes, commonly known as status offenses, include truancy, curfew violations, runaways, and general misbehavior—persons in need of supervision, persons judged unmanageable, incorrigible, and beyond control; persons in need of care and protection, and so on. Children convicted of such offenses may be incarcerated in a juvenile hall or even an adult jail, if there are no juvenile facilities available (Chesney-Lind, 1988b; Shelden, et al.). In such cases, even though they have not committed crimes, young people serve time alongside adult criminals convicted of rape, robbery, aggravated assault, and even murder.

Females are more likely to be arrested and referred to court for status offenses, despite indications that male status offenders are more likely to escalate into serious crime (Shelden, et al.). The National Center for Juvenile Justice said that in 1982, 30% of the girls in court, but only 10% of the boys, were charged with status offenses. Girls made up almost half (46%) of the juvenile justice defendants, even though boys committed 80% of the serious crimes (cited in Chesney-Lind, 1988b). In terms of arrests, 25.2% of all girls' arrests in 1986 were for status offenses, compared to only 8.3% for boys (Chesney-Lind).

Although more girls are arrested for status offenses, self-report studies show that they do not actually engage in more delinquent behavior than boys. When asked to report on their own behavior, boys and girls admitted to similar incidents of alcohol and drug use, truancy, sexual intercourse, and stealing from the family. (Young people can be arrested for all of these activities.) In a study of 2,000 youths (Figueira-McDonough, 1985), researchers found girls and boys have similar involvements in status offenses. Another study (Canter, 1982) found that boys reported a greater number of status offenses than girls.

A study of girls' runaway and incorrigibility (Teilmann & Landry, 1981) found a 10.4% over-representation in girls' arrests for incorrigibility. The study concluded that girls are more likely than boys to be arrested for status offenses, when contrasted to their self-reported delinquency rates.

There are several ways to interpret these findings. The most common theory is the difference in social expectations. "Girls are more often charged with being 'ungovernable,' in part because their usual passivity makes any departures from submissiveness conspicuous" (Rogers, p. 529). Rogers explains that the same delinquent behavior would often be ignored, or even condoned, in boys.

Another factor is that girls' parents are more likely to involve the juvenile justice system in disputes with their daughters (Chesney-Lind, 1988b). Parents often initiate a status offense referral by calling the police. One study found that 72% of status offenders are turned in by relatives (Ketcham, 1978, cited in Chesney-Lind).

Who Are the Female Delinquents?

Like other areas of psychological research, most studies of juvenile delinquency do not include girls (Rogers, 1962; Cernkovich, 1979; Chesney-Lind 1989). But there have been studies specifically about girls, which reveal interesting information about their backgrounds. Specifically, research has shown that a majority of female delinquents come from dysfunctional or broken homes (Rosenbaum, 1989; Chesney-Lind, 1988a, 1989). In Rosenbaum's study of 240 girls from the California Youth Authority (CYA), only 7% came from intact families. Another 25% lived in two-adult homes, although foster homes, homes of other relatives, or homes where the mother lived with one of a succession of husbands or boyfriends were included. Three-quarters of the girls (76%) came from homes where there was at least one other family member with a criminal record; in these cases one-third of the mothers and fathers (32% and 30% respectively) had criminal records. Of the mothers with criminal records, 50% had been arrested for felonies. The study found that 34% of the fathers and 31% of the mothers were known alcoholics; 81% of the families reported conflicts over alcohol in the home. In addition, 29% of the fathers and 27% of the mothers were diagnosed neurotics or psychotics.

Another study of runaways (Farber and Kinast, 1984) found "an astounding amount of violence was directed toward youth who ran away." In that study, 37% of the mothers had been charged with abuse and/or neglect. Other studies have also revealed high levels of family violence, alcoholism, and mental illness. One researcher suggests that the status offense laws give parents the ability to "invoke official agencies of social control in their efforts to keep young women at home and vulnerable" (Chesney-Lind, 1989, p. 24).

In her analysis of family dysfunction, Rosenbaum argues that runaway girls leave home "to break the generational cycle of despair" (p. 40). She criticizes the juvenile justice system, saying that runaway girls become double victims: victims of both their abusive families and the criminal justice system.

In her study, Rosenbaum found that girls arrested for runaway were more likely to be held in detention than boys. Then upon release, authorities tend to return girls to their families, no matter how abusive the environment. Even when the girls were made a ward of the court, Rosenbaum found that they were usually sent home. One girl was returned to her family even though home was sometimes an abandoned car; another was returned to a home that a social worker had described as "an animal-like environment." One girl was returned home after her mother's release from prison. Although the mother had been convicted of throwing lye in a lover's face, the case worker believed "the girl had not been too damaged" by her mother's actions (p. 41). Rosenbaum criticized society's blind faith in the family unit and the notion that it is always best to return girls to their natural family.

Chesney-Lind explained that the double victimization of girls amounted to blaming the victim (1988a, p. 146). In other words, a girl who runs away from an abusive home to protect herself is later identified as the criminal. Chesney-Lind cites a 1982 study (Phelps, et al.), which showed that 79% of delinquent girls in Wisconsin detention facilities were victims of physical abuse. The abuse ranged from bruises, welts, and pain, to being knocked unconscious (21%), to broken bones (12%). In addition, 50% reported being sexually assaulted, and 32% said they had been sexually abused by parents or others close to their families.

Attitudes Toward Female Juveniles

The theory that the status offense laws are applied more severely to girls than to boys has stirred controversy in academic journals. Meda Chesney-Lind, an associate professor at the University of Hawaii, Manoa, has published a number or articles on the subject over the last 15 years. In "Girls' Crime and Woman's Place: Toward a Feminist Model of Female Delinquency" (1989), she calls the juvenile justice system a "major force in girls' oppression" and accuses the system of being "abusive and arbitrary" (p. 11). Because she offers a convincing historical analysis, her arguments will be explained here.

Chesney-Lind begins her criticism of delinquency theory by saying that it has "virtually ignored female delinquency" (p. 10). Most studies only involve boys' crime rates, and further, most studies only investigate serious crimes, ignoring status offenses altogether. Because the scholarly research has been slanted, Chesney-Lind questions whether the existing theories of male delinquency can adequately explain female delinquency. Most research in this century has concentrated on lower-class male delinquency, especially gang activity. Chesney-Lind calls this the "West Side Story Syndrome" (p. 11), because it only considers gang activity, a small percentage of all juvenile delinquency. She argues the urgent need to rethink current delinquency models.

Chesney-Lind explains that the movement to establish a separate institution for juveniles started in the early part of this century. It grew out of a wider social purity movement, which was a crusade against prostitution, child slavery, and other social evils. Women reformers who wanted to enter the traditionally male political arena found the childsaving movement a safe cause in which to invest their energies. Even women like Susan B. Anthony joined the social purists to oppose prostitution and raise the age of consent for girls. But ultimately, Chesney-Lind notes, "many of the early childsavers' activities revolved around the monitoring of young girl's, particularly immigrant girls', behavior to prevent their straying from the path" (1989, p. 15).

Almost all girls brought to family court during this time were charged with immorality or waywardness. These charges essentially meant evidence of sexual intercourse. Upon arrest, girls faced lengthy and embarrassing interrogations from social workers and arresting officers. They were also subject to gynecological examinations to determine the condition of the hymen. Results were noted on their official records.

Girls found guilty of immorality were severely penalized. During the years 1899 and 1909 in Chicago, where the first family court was founded, 50% of girl delinquents, but only 20% of boy delinquents, were sent to reformatories. In Milwaukee and Memphis, girls were twice as likely to be committed to training schools. Other studies have shown similar results, and further, the average length of incarceration for girls was five times that of boys (pp. 15-16).

Many girl's reformatories and training schools were built during that period. They were called places of rescue and reform and were meant to isolate girls until marriageable age. Chesney-Lind said the people who set up the laws, the family courts, and the reform schools were simply "obsessed with precocious female sexuality" (p. 16). She traced these attitudes into the present day by quoting a contemporary judge who said, "Why, most of the girls I commit are for status offenses. I figure if a girl is about to get pregnant, we'll keep her until she's 16 and then the ADC [Aid to Dependent Children] will pick her up" (p. 16).

Chesney-Lind points out an irony in contemporary juvenile delinquency theory. The juvenile justice system essentially grew out of a crusade against girls' sexual promiscuity, yet most studies only involve male subjects. She said this inconsistency is critical for girls, who are the clear losers in the reform effort. Even though girls are charged with less serious offenses, they are not treated less severely in the courts and detention facilities where they serve their sentences (pp. 10-11).

Chesney-Lind and others have shown, by analyzing self-report statistics, that boys take part in status offenses with about the same frequency as girls. They indicate that the difference in girls' and boys' crime statistics are due to differential enforcement of the laws. Boys' behavior is tolerated, while girls are arrested, tried, and sentenced to institutions for less serious crimes.

Female Delinquency in the 1930s

Understanding the development of the juvenile justice system in the first half of this century is essential to understanding attitudes toward female delinquency. Journal articles from the 1930s and 1940s give further insights into academic opinion on the subject.

"Cultivating a Wild Rose," published in a 1930 University of Pennsylvania journal, reveals one woman's thoughts about the problem of waywardness. In her article, Marion Braungard, a Philadelphia social worker, relates the story of an 18 year old girl named Rose. Being unable to tolerate Rose's waywardness, the girl's parents brought her to the University of Pennsylvania Psychological Clinic where Braungard worked. After an initial psychiatric evaluation, a doctor diagnosed Rose as a "psychopathic inferior" who had "much more extensive experiences than her family had suspected" (p. 285). The doctor recommended an intensive counseling program, which Rose abandoned after the first several meetings.

Shortly thereafter, Rose ran away from home for three days. She finally returned in the middle of the night in the company of a woman "connected with a house of ill fame." (p. 285) Relations at home deteriorated and Rose returned to the clinic for counseling, but then dropped out again. A year after the first encounter with Rose, Braungard learned that a court committed Rose to the Sleighton Farm reformatory school. After serving her sentence, Rose visited the clinic to "renew her acquaintance" with Braungard.

Throughout the article, Braungard gave her subjective observations and opinions. She said she felt sorry for the wayward girls and their families, but supported the prevailing theory that waywardness and immorality are a psychological deficiency. She said, "[of the] cases which come to the Psychological Clinic, I have come to expect that when there is a limited moral stamina, the essential character of the girls is not apt to be altered" (p. 283). Braungard stated that the ideal outcome for wayward girls was to "adjust themselves inconspicuously in society" (p. 283). This shows that in 1930, a girl or woman was thought to be socially acceptable only if she conformed to the stereotype of extreme femininity, i.e. being inconspicuous. Braungard reflected these values in other statements as well. When she learned that a judge had committed Rose to a Sleighton Farm, Braungard lamented that Rose's "non-conformity . . . brought her into sufficient conflict with society to distinguish her from the normal group" (p. 288).

Braungard described the chain of events leading to Rose's confinement:

"[Rose] had been lax in her relations with men to such an extent that the family could no longer ignore the situation. Gossip in her neighborhood assigned her the responsibility for the venereal infection of several boys in the neighborhood. She denied the accusation and offered to go to court for an examination to prove that she was not infected herself. The test results were negative, but her attitude and manner were so unbearably arrogant and bold, that the family requested that she be committed to Sleighton Farm as a possible means of bringing her to her senses" (p. 288).

In the last two pages of her article, Braungard praised Sleighton Farm for bringing about a change in Rose's character. Braungard said, "Sleighton Farm played the part of the proverbial darkest hour which precedes the dawn" (p. 288). Braungard explained that the story had a happy ending because the family moved to a new town, where Rose didn't have a bad reputation. She concluded her report by saying, "Three months have passed and Rose's conduct has been entirely satisfactory to her family, and she in turn is reasonably in accord with them. Let us touch wood!" (p. 290).

Braungard's article gives direct evidence that society truly embraced the idea of reform schools for female status offenders. Although she did not write the article for the purpose of endorsing or propagating the system, it clearly served that purpose. It is difficult to estimate how many people read this specific article when it was published, but it nonetheless demonstrates the prevailing notions about girl delinquents.

The only inconsistent factor in the article was one statement by the psychiatrist who originally evaluated Rose as a psychopathic inferior. He said the girl's family had been too strict with her and recommended that they give Rose more freedom, especially in her relations with men. The family failed to do this, however, as they observed Rose's waywardness progress. Braungard mentioned the doctor's comments in the beginning, but never placed any further responsibility on the parents. It is unlikely that anyone remembered the doctor's comments when the girl's parents took Rose before a judge to have her committed to the reform school.

In this regard, Chesney-Lind said, "Juvenile justice workers rarely reflected on the broader nature of female misbehavior or on the sources of this misbehavior. It was enough for them that girls' parents reported them out of control" (1989, p. 17).

More of the Same in the 1940s

The next decade showed little change in the treatment of female delinquents. Two articles from the era (Castendyck & Robison, 1943; Harris, 1944) demonstrate a growing concern over the problem of female juvenile delinquency. Again, the main focus of female delinquency was sexual promiscuity, referred to as sex offenses and ungovernable behavior. (Generally, sex offenses include prostitution, which is a more serious crime; ungovernable behavior can be interpreted as general sexual promiscuity.)

One article, "Delinquency in Adolescent Girls," was written by a man, Dale B. Harris. He cited statistics about the rise in female delinquency, saying there had been a 100% increase in sex delinquencies among minor girls in a two year period (p. 596). The other article, "Juvenile Delinquency Among Girls," written by two women, Castendyck and Robison, acknowledged that there had been much publicity about a rise in female delinquency, including "items and articles in the daily press and popular magazines of today; in the reports of studies, investigations, and recommendations for programs appearing in scientific and professional literature; and in the requests for information and advice received almost daily by the Children's Bureau from individuals and community groups" (p. 253).

Harris offered possible reasons for the increase in female delinquency: "social change in general and relaxation of sex mores in particular" (p. 597). He especially noted women's move into the work force as a cause of sexual promiscuity, especially night shifts and "morally hazardous" jobs that "offer the opportunity for casual sex," i.e. waitresses, domestic workers, and hotel maids. As he noticed, "on every hand one encounters girls of less maturity and social experience in jobs that offer opportunities for casual sex contacts" (p. 598).

He listed other factors affecting female delinquency: mobility of families and young people; lessening of "attention, supervision, and control given to children and youth"; general war-time insecurity, and in a tip of his hat to Freud, "strong recrudescence of primitive impulses in war" (p. 601). Like many of his contemporaries, Harris believed that there was an increase in female delinquency and that it was "a true indication of the stress" in World War II society (p. 601).

The article by Castendyck and Robison challenged then-standard female delinquency theories. They reviewed the popular list of reasons for a rise in female promiscuity—citing the exact same things as Harris—but then added their own explanations for the increase. They proposed that the public outcry about female delinquency was responsible for increased arrests. They believed that public opinion had influenced the policies of the police and court system.

They said the statistics "clearly indicate that communities are more concerned about the behavior of girls now than they were before the war." But they stated further, "Unfortunately, what the statistics do not reveal is whether there is more reason for the concern" (p. 260). They pointed out that statistics were not a real measure of the incidence of deviant behavior, but only an indication of an increase in arrests and sentencing. They asserted that public opinion had changed due to "the removal of some of the taboos of the past" which had allowed society to "meet [promiscuity] more realistically than was the case 25 years ago" (p. 262). In other words, Castendyck and Robison believed that there may not have been an actual increase in female sex offenses, only an increase in the number of cases reported and prosecuted.

From these two articles, it is evident that there was a lot of concern about female delinquency. For whatever reasons, girls were tried and sentenced for their sexual behavior in greater numbers during World War II. Castendyck and Robison suggested that the increase resulted from more strict enforcement of the laws. This supports the theory that female delinquents are over-represented in court populations.

Contemporary Thought

In the 1940s, some sociologists and criminologists tried to prove that World War II caused an increase in female delinquency. In the 1960s, various studies tried to prove that the Women's Movement caused an increase in female delinquency (Alder, 1975; Simon, 1975; cited in Cernkovich, 1979). In the 1970s and 1980s working mothers were blamed for an increase in their daughters' (but not their sons') delinquency (Chesney-Lind, 1989). Further research and statistical evidence, however, has discredited these notions.

While sexual conduct was seen as just cause for imprisonment of girls through the first half of the century, the 1960s and 1970s brought a change in attitude. A textbook on juvenile delinquency (Caven & Ferdinand, 1975) said, "With the sexual revolution and the liberation of women, much sex behavior that was previously regarded as morally blameworthy and legally culpable is today viewed at most as questionable" (p. 157). The textbook explained that intercourse between unmarried juveniles is still against the law if the girl is below the age of consent. There are other sex violations that are also illegal, such as rape and prostitution.

According to the textbooks and popular opinion, it appears that there was a change of attitude toward status offenses in the early 1970s. In fact, in 1974, a law was passed to decriminalize status offenses. Commonly known as the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act of 1974, it encouraged public facilities to discharge status offenders not charged with other, more serious crimes. For eight years following the enactment of the law, incarceration of girls in training schools and detention centers fell dramatically, as did convictions of new offenders.

However, this period was followed by a period of get tough policies that resulted in increased arrests and convictions of female status offenders (Chesney-Lind, 1988a). Judges and police officers, especially, spoke out against the laws, claiming that juveniles would now be free to run away from home, miss school, and disobey their parents and the courts. Judges also found ways to circumvent the new law by issuing criminal contempt citations to elevate non-criminal offenders into law violators. Violation of probation was another way to make a status offense appear as a more serious crime. A youth on probation could be put back in juvenile hall simply by a phone call from the parents to the probation officer.

In 1974 the federal government implemented the deinstitutionalization laws to reduce the number of non-criminal juveniles in the nation's detention facilities. Starting at the time the bill was passed, resistance from judges and others in law enforcement was evident. The latest attack on the deinstitutionalization laws came in 1986 with the concern about missing and exploited children. The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (1986, cited in Chesney-Lind) recommended that "Congress should amend the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act to ensure that each state juvenile justice system has the legal authority, where necessary and appropriate, to take into custody and safely control runaway and homeless children."

Most states have resumed the practice of arresting juveniles for status offenses, even though the 1974 law was never modified. The return to pre-1974 statistics for status offenses, has also meant a return to disproportionately higher arrests of female status offenders. Chesney-Lind argues that as a result of the 1974 law, "there may be some evidence in some parts of the country that girls are receiving more equal treatment [but], it is still likely that they are being placed in training schools for less serious offenses than their male counterparts" (Chesney-Lind, 1988a, p. 154).

Chesney-Lind criticizes the juvenile justice system and its attempt to reform itself by saying,

"It does not take great wit and keen foresight to conclude that those who oppose deinstitutionalization are mounting a strong effort to divert federal attention away from status offenders . . . Judicial sexism has haunted the juvenile justice system since its inception and has survived despite the substantial, though indirect, attempts at reform represented by the Juvenile Justice Act of 1974" (1988a, p. 160).

Chesney-Lind criticizes the juvenile justice system, saying, "What may be at stake in efforts to roll back deinstitutionalization efforts is not so much 'protection' of youth as it is curbing the right of young women to defy patriarchy (1989, p. 26).

Conclusions, Suggestions, Opinions

I agree with Chesney-Lind and think her research is a valuable contribution to the feminist movement. Just making people aware of the unequal treatment of girls is important work. People who aren't involved in counseling services or in the juvenile justice system probably think girls are no longer jailed for their sexual behavior. But studies by authors like Chesney-Lind prove it is still quite common.

In addition, while studies suggest that most female status offenders come from abusive homes, girls' complaints about their homes have been routinely ignored. Chesney-Lind therefore recommends that more research is needed into the backgrounds of the girls convicted of status offenses. She said, "Time must be spent listening to girls" (1989, p. 25). She accuses the juvenile justice system of criminalizing girls' survival strategies (1989, p. 24). Chesney-Lind also mentioned a need for more research on the reaction of official agencies to girls' delinquency. Although difficult to quantify, she insists this data is necessary to develop a delinquency theory that is sensitive to gender as well as race and class.

Chesney-Lind opposes the juvenile justice system and fears that, unchecked, it could return to 1930s-style repression. Chesney-Lind said, "Unless women's groups begin monitoring their juvenile courts to prevent further erosion of the victories of the [1974] deinstitutionalization movement, the world is likely to see, once again, the jailing of large numbers of young women 'for their own protection' " (1988a, p. 160).

I think imprisoning girls for truancy and sexual deviance seems a simplistic, brutal way to deal with the "Woman Question." During the Industrial Age, the market economy supplanted women's vital role as homemaker. Women's identity and purpose became a subject of debate, which is still referred to as the woman question. To answer the woman question, romanticists idealized them as homemakers (with little to do) and spurned them as temptresses. When young women fell into the role of temptress, the juvenile justice system was formed to usher them into detention camps until they realized the wrong of their ways. It is frightening to realize that remnants of this system still exist today.

I also think it is unfair to cast all the blame for sex offenses on women. Most sex offenses involve a man and a woman; a boy and a girl, or a man and a girl. It seems unfair that sexual behavior is condoned or ignored in boys, but condemned in girls. Learning about this subject has been interesting and frustrating at the same time. There are many aspects of the problem I have not mentioned in this paper. In the future I would like to study the issue of female delinquency in more depth.

References

Braungard, Marion. (1930). Cultivating a Wild Rose. The Psychological Clinic, Vol. 28, 282-290.

Canter, Rachelle, J. (1982). Sex Differences in Self-Report Delinquency. Criminology, Vol. 20, 273-393.

Castendyck, E. & Robison, S. (1943). Juvenile Delinquency Among Girls. The Social Service Review, Vol. 17, No. 3, 253-264.

Cavan, R.S. & Ferdinand, T.N. (1975). Juvenile Delinquency (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co.

Cernkovich, S.A. & Giordano, P.C. (1979). A Comparative Analysis of Male and Female Delinquency. The Sociological Quarterly, Vol. 20, 123-128.

Chesney-Lind, M. (1988a). Girls and Status Offenses: Is Juvenile Justice Still Sexist? Criminal Justice Abstracts, Vol. 20, 144-165.

Chesney-Lind, M. (1988b). Girls in Jail. Crime & Delinquency, Vol. 34, No. 2, 150-164.

Chesney-Lind, M. (1989). Girls' Crime and Woman's Place: Toward a Feminist Model of Female Delinquency. Crime & Delinquency, Vol. 35, No. 1, 5-29.

Farber, E. & Knast, C. (1984). Violence in Families of Adolescent Runaways. Child Abuse and Neglect, Vol. 8, 295-299.

Figueira-McDonough, Josefina. (1985). Are Girls Different? Gender Discrepencies Between Delinquent Behavior and Control. Child Welfare, Vol. 64, 273-289.

Harris, D.B. (1944). Delinquency in Adolescent Girls. Mental Hygiene, Vol. 28, 596-601.

Martin, D. (1988). A Review of the Popular LIterature on Co-dependency. Contemporary Drug Problems, Vol. 15, No. 3, 383-389.

Phelps, R.J., et al. (1982). Wisconsin Female Juvenile Offender Study Project Summary Report. Wisconsin: Youth Policy and Law Center, Wisconsin Council on Juvenile Justice.

Rogers, D. (1962). The Psychology of Adolescence. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Rosenbaum, J.L. (1989). Family Dysfunction and Female Delinquency. Crime & Delinquency, Vol. 35, No. 1, 31-44.

Shelden, R.G., Horvath, J.A., & Tracy, S. (1989). Do Status Offenders Get Worse? Some Clarifications on the Question of Escalation. Crime & Delinquency, Vol. 35, No. 2, 202-216.

Teilmann, Katherine, S. & Landry, Pierre Jr. (1981). Gender Bias in Juvenile Justice. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, Vol. 18, 47-80.

Windle, M. (1989) Substance Use and Abuse Among Adolescent Runaways: A Four-Year Follow-Up Study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, Vol. 18, No. 4, 331-344.

Analysis of [Juvenile Correctional Facility]

Introduction

[Juvenile Correctional Facility] is a juvenile training school, part of the State's Close Custody Juvenile Corrections Program. Located in southeast [city], [the reform school] offers residential care for adolescents, aged 12 to 18, who have been adjudicated by the [State] juvenile court. Originally, [Juvenile Correctional Facility] was only for female delinquents, but it now accepts both boys and girls. [Juvenile Correctional Facility] only takes juveniles who have been convicted of a delinquent act, which if done by an adult, would constitute a crime. The typical violations of [Juvenile Correctional Facility] students include person-to-person crimes (such as assault or murder), drug offenses, sex offenses (child molestation or rape), theft, burglary, vehicle theft, and other index crimes. The school does not accept status offenders, if the status offense is the most serious offense. They do, however, take female parole violators. Therefore, the most recent precipitating incident for some of the girls may still be on the level of a status offense. It becomes a serious crime because it was committed while the girl was on parole.

The population at [Juvenile Correctional Facility] is becoming more hard-core. This is because the school has a cap of 170 students. Cap refers to the maximum number of students they can take at a time. But since the school is always full, there is a waiting list. Thus, the the Closed Custody Review Board (CCRB) decides when to release less-delinquent students to make room for more seriously delinquent juveniles. This process assures that only the most seriously criminal students stay. The unit directors at [Juvenile Correctional Facility], the juveniles' respective parole officers, and ultimately [Juvenile Correctional Facility] Supervisor Mary E.E., all play a part in deciding who to release.

Facilities and Care at [Juvenile Correctional Facility]

[Juvenile Correctional Facility] offers residential care, academic education, and therapeutic treatment. The therapeutic treatment focuses on juveniles' substance abuse, sexual abuse, and sex offender issues. Although the program does not claim to cure these problems, the stated goal is to give students the knowledge to make better life decisions. Previously, [Juvenile Correctional Facility] did not offer therapeutic treatment, but several qualified counselors and social workers have joined the [Juvenile Correctional Facility] staff within the last six years to develop treatment programs.

[Juvenile Correctional Facility] is divided into three sections: the school, the administration, and the cottages. The school, located in a central building on the [Juvenile Correctional Facility] property, consists of a principal, teachers, and teacher's aides. The juveniles are in school four days a week, from morning until three o'clock. The rest of the time they participate in activities or group meetings in their cottages, or work in various jobs on campus. The school recently acquired several computers through a grant, and thus now offers computer training to some students.

The administration, located in a building close to the entrance of the campus, includes clerical and reception staff, the superintendent and her staff, parole officers, two chaplains, a minority advocate, a sex offender treatment counselor and his assistant, and a drug and alcohol counselor. The other [Juvenile Correctional Facility] departments are security, maintenance, recreation, and food services. The supervisor oversees all activities at [Juvenile Correctional Facility]; the supervisor and the whole school are under CSD, the [State] Children's Services Division.

The nine cottages, each named for letters of the Latin alphabet, do not resemble cottages at all. They are actually wards in brick, prison-like buildings, with heavy, locked, metal doors. Since all the buildings are locked, staff and faculty must pick up their security keys at the beginning of each workday and turn them in when they leave. The [Juvenile Correctional Facility] resembles an ordinary campus, with the cottages playing the part of dormitories, where all the students live. The facility is not surrounded by a fence, so there are occasional runaways. Despite the runaway problem, the [State] wants the facility to maintain its school-like atmosphere, so they have never built fences or walls to make it more secure.

The cottages, with approximately 17 juveniles in each, are managed by GLC staff, or Group Life Coordinators. The GLCs are divided into levels: GLC I, GLC II, GLC III, and so on. Levels one and two are essentially line staff, or union workers, who give Direct Care. Essentially, this means they play the part of parents for students under their care. GLC III and above are managers. A GLC III is usually called an assistant manager, a GLC IV is usually called a manager, and each cottage also has a counselor, or unit director, who handles casework and designs treatment programs. The unit director is technically called a GLC V, but the term GLC is not generally used to refer to managers or counselors.

The nine cottages are divided by type of treatment plan, as follows: Delta and Omega have a program for boys that includes Guided Group Interaction (GGI), a treatment modality based on daily group meetings in a peer-culture milieu. Alpha (for boys) also uses GGI, with an emphasis on drug and alcohol treatment. Theta, primarily female parole violators, uses Reality Therapy as its treatment modality. Iota, the intake cottage for girls, uses the GGI process, with an emphasis on drug and alcohol treatment. Kappa and Sigma are the male sex offender wards, primarily geared toward younger boys. Zeta is the only co-educational cottage in the entire [State] closed custody system. The treatment modalities are milieu and individual counseling. Gamma is specifically for boys aged 12 to 15 who need ongoing treatment with feedback on social expectations. All the cottages have drug and alcohol groups and sex abuse groups.

GGI, which is used in almost all the cottages, originated in the 1940s, post World War II era in America. The basis of GGI is to create a group atmosphere where each member helps the others work toward their rehabilitation goals (Kratcoski, 1989; Trotzer, 1989). It is a precursor to positive peer culture (PPC), where the peer group supports positive change. According to Kratcoski, "The key element of guided group interaction is the problem-solving activity that takes place in the group meetings" (p. 270).

The cottages rely on institutional behavior modification to regulate the juveniles' day-to-day activities. For example, in the Kappa cottage, one of the two sex offender treatment programs, there is a public bulletin board in the day room listing all the students' names from top to bottom, and all the daily activities from left to right. If a boy successfully accomplishes a task or completes an activity, he gets a green dot next to his name. If he does a satisfactory job he gets a yellow dot; a red dot indicates unsatisfactory behavior. Boys with good records earn privileges and work their way through the program. Red dots result in lost privileges.

Behavior modification is standard in most juvenile facilities, but it also has many critics. Some contend that it is little more than a tool to control behavior inside an institution, which has no lasting therapeutic value (Brown, Wienckowski, & Stolz, 1989).

The Journal

My First Visit to [Juvenile Correctional Facility]

The [Juvenile Correctional Facility] struck me as being very 1940-ish—naming the cottages after Latin letters (stylish during that era), using GGI and classic behavior modification (first used in that era), the buildings themselves (probably built around that time), and the idea of a reform school itself (which actually goes back further, to the 1920s). I had not heard anything in particular about [Juvenile Correctional Facility], but I worked in a juvenile hall once and I've had other experiences with institutions. I figured [Juvenile Correctional Facility] would be big and bureaucratic, with some unqualified staff, and lots of politics. I admit I projected these prejudicial ideas on [Juvenile Correctional Facility] before setting foot on the property.

I was pleasantly surprised, however, when I met D.B., the sexual abuse treatment coordinator, because he did not seem like a stereotypic bureaucrat or heartless institutional worker. D.B. is a licensed social worker (LCSW), who graduated from Portland State University eight years ago. He is one of the people [Juvenile Correctional Facility] hired to develop therapeutic treatment. For the last six years D.B. has been developing the sexual abuse treatment program. His responsibilities include evaluation and diagnostic assessments of juveniles; statistical reporting; testifying to the legislature and in court; acting as a liaison with the community, other agencies, and institutions; and making referrals. He also teaches part-time at [a local] Community College and helped develop their sexual-abuse treatment curriculum.

I also met S.F., a woman hired that month to assist D.B. She was also a non-bureaucratic, non-institutional, genuine human being. Before coming to [Juvenile Correctional Facility] she worked at the Women's Crisis Center in [City], in the State Hospital sex offender treatment program (Ward 41-B), and helped her husband run a small business. S.F. has a BA in psychology, but plans to pursue her master's degree in the field of counseling, criminal justice, or a related field.

My first week at [Juvenile Correctional Facility] I helped S.F. set up the sexual abuse victim groups in the cottages. We went to each cottage to introduce ourselves and set a tentative schedule. We also screened students to find out who needed and wanted to be in the groups. S.F. had a special way of talking to the students. She seemed to be able to get right on their level and listen to what they said. The kids responded to her by revealing their thoughts, fears, and their desire to be involved in the groups.

Once a few groups were set up, S.F. assigned two counselors to each group. D.B., S.F., myself, another practicum student, and one of the chaplains, Father Ted, were each assigned to facilitate or co-facilitate several groups. A facilitator leads the group and a co-facilitator works with the main facilitator to carry out the group process. I was assigned to be a co-facilitator in two victims' groups in Kappa cottage. D.B. and S.F. also asked me to do art therapy with the students, since I told them I was planning to write my thesis on art therapy. S.F. bought art supplies, but neither of us knew exactly when, where, or how art therapy would fit in.

All and all I was happy to be at [Juvenile Correctional Facility], working with D.B. and S.F. They were helping me overcome my prejudicial image of [Juvenile Correctional Facility]. S.F. and I talked for several hours one day, telling each other our whole life stories. We also talked about [Juvenile Correctional Facility], juvenile delinquents, the system, politics, philosophy, and 12-step. She seemed to have a lot of compassion for distressed adolescents and chose to be in the field out of a genuine desire to help. I also had an hour-and-a-half talk with D.B. one day and I came out having a great respect for the work he is doing, too. Out of the huge jungle of bureaucracy and impersonalism I imagined the place to be, I was happy to have found two friends.

The First Group Meetings

On my sixth visit to [Juvenile Correctional Facility], I was to go to Kappa cottage to co-facilitate my first victims' group. Before going to the cottage, however, I stopped in at the office to talk to S.F. She warned me that the woman who would lead the group, Miss B., was into power and control and might be hard to get along with. She said Miss B. is a GLC on the Kappa ward who had formed the groups herself by putting eight boys in one group and nine in the other. Since the cottage houses only male sex offenders, Miss B. had assumed that all the boys should be in a victims' group, without waiting for S.F. to screen anyone. S.F. told me she thought the groups were too large, adding that if Miss B. didn't do a good job, D.B. could replace her as group leader. S.F.'s warning about Miss B. made me apprehensive, but I was willing to give it a try. After the briefing I walked to Kappa cottage.

My initial impression of Miss B. was a self-fulfilling prophecy, because the first thing that happened seemed to indicate that she was into power and control. Just when I got to the cottage the boys came back from school. One of them reported to Miss B. that another boy, Ted, had stabbed him in the leg with a pencil and broken the lead off under his skin. Miss B. reacted by yelling, "Ted! In your room right now!" The boy, Ted, threw a tantrum and had to be ushered to his room by another GLC. Once inside, Ted repeatedly banged the door with his fist. At this, Miss B. called security and a guard came to the cottage to subdue the boy and take him away. Miss B. told me this was called a QR, and when asked, explained that there is a Quiet Room in one of the other cottages where the boy would be held for the rest of the morning.

I was shocked at the incident and felt sorry for the boy. In my Clinical Child and Youth Work class two nights before, we heard a lecture by Steve Young of the Waverly home for emotionally disturbed children. He spoke of a humanistic approach to dealing with rebellious adolescents, based on a philosophy of do no harm. This means that above all, the worker should not cause further damage to the child. Steve emphasized that staff members have an obligation to be respectful and compassionate toward the children under their care. He described the stages of temper tantrums and how to intervene at each stage. He said physical restraint was a last resort, since going through the temper tantrum with the child would help the child get in touch with his/her feelings. Waverly is based on a mental health model, whereas [Juvenile Correctional Facility] is based on a corrections model that is in transition to being a treatment model. The QR incident went against everything I had learned in school, but I tried remain detached. After all, I was a visitor and wanted to keep an open mind. Nevertheless, the incident revived my opinion of [Juvenile Correctional Facility] as an impersonal, monolithic institution with an unfeeling, power-and-control-motivated staff.

When the QR was over, we started the victims' group meeting. The group was relatively large: eight juveniles, plus Miss B. and myself. It was only their second meeting, but since they already knew each other from being in the same cottage day after day, Miss B. dove right into some intense subjects. After having each boy tell me their names, she had each say what their victimization issues were. I felt uncomfortable listening to these painful incidents and I imagined the boys felt uncomfortable disclosing in front of a stranger.

If a boy resisted Miss B.'s instructions to disclose, she tried to force him, saying things like, "We can't play these games with you. If you won't cooperate, maybe you should leave the meeting," and so on. I strongly objected to the way she was handling the boys because it seemed like they were afraid and she was trying to use intimidation to make them confess. I was getting angry because I thought she didn't understand how painful these abusive incidents must have been to the kids. It's not like talking about what you ate for lunch yesterday—the abuse issues are the most painful secrets these kids hold.

During our third victims' group I couldn't sit still and listen to Miss B.'s coercive tactics any longer. I spoke up saying that I didn't think we should use force to make the kids talk. She tried to argue, but since we were right there in front of all the kids she acted like she would rather brush the whole confrontation aside. There definitely was a conflict, though, and she called me into her office after the meeting to explain why I was wrong and she was right. I repeated that I didn't think it was fair to force the kids to disclose. She finally said, "Okay, we both have different philosophies."

When I told S.F. about the incident she assured me that she supported what I had done. She said she didn't like the way [Juvenile Correctional Facility] lets unqualified people lead groups and she was glad I spoke up. I knew S.F. would go along with what I did, or I probably would have been afraid to do it. I also knew D.B. wouldn't mind.

When I went back to [Juvenile Correctional Facility] the next Thursday I didn't know what to expect, but hoped everything would be okay. I went to check in with D.B. and S.F. but walked straight into a meeting between D.B. and Miss B. They invited me to join them.

D.B. started out by explaining that the theories I was learning in grad. school may be different from the institutional point of view. Miss B. said that my outburst the previous week had left some of the kids wondering who was right or wrong. I agreed that it must have been awkward, and apologized. Then I explained that the way I saw it, some of the kids were very open about disclosing their victim issues, while others were not ready. D.B. and Miss B. considered what I said and asked what I would do about it. I said I would like to do art therapy with several of the most reluctant kids to see if they could draw their feelings. After putting feelings down on paper, maybe they would be willing to talk about their drawings. I said I would like to take about three kids (each day, Thursday and Friday) and work with them in another room.

I was so relieved when Miss B. agreed. I know I must be somewhat of a thorn in her side, to use an old cliché. But in an institution like [Juvenile Correctional Facility] it would be impossible to do anything unusual and not be a thorn in someone's side. Since the meeting I have gotten to know Miss B. a little better and I've realized we can get along okay. Besides, I'm grateful that she agreed to let me do art therapy in her cottage.

Thus far I have done two art therapy groups, but only one boy was available for the last session. (Miss B. had not yet decided who should be in the Friday art group, so I only got one boy last Friday.) I think art is a good way for these adolescents to communicate their feelings. I have learned so much about each boy simply by asking them to draw a picture. For example, one boy, who has a violent family history, drew a picture of a battleship on a bloody ocean, with black storm clouds and lightning. Another boy portrayed an optimistic attitude when he drew a picture of himself winning first place in a car race. He said it was a picture of his future. Both boys were very proud of their drawings; the boy who drew the battleship apparently has more serious problems he needs to work out.

I am planning to continue at [Juvenile Correctional Facility], at least with these two groups, for the time being. I am grateful to Miss B. for trying to be open minded. Without her cooperation I would have been forced to start all over in a new cottage. I want to continue working with these kids because I've already started getting to know them. I am also grateful to S.F. and D.B. for their support.

Aftermath

Out of curiosity I talked further with D.B. about [Juvenile Correctional Facility]'s sexual abuse treatment policies. I asked him why Miss B. was leading groups if (as S.F. said) she wasn't qualified. He said Miss B. is a GLC II, and while GLCs are not supposed to be treatment-, or therapy-oriented employees, Miss B. is a counselor-in-training. As such, she is allowed to lead groups, and has been doing so for three years. D.B. said she needed more training, but since she was enthusiastic about leading groups, and a dedicated employee of six years, he wanted to let her get group experience.

I asked him to explain the circumstances around how Miss B. started the group and why I got involved. He said, "I believe they [Miss B. and other Kappa GLCs] got ahead of themselves and just went ahead with [the groups], instead of saying, 'Wait, hold on, we need somebody.' And that's a real common thing to happen in institutions" (Bucklin & Muster, 1990). In other words, when he and S.F. were in the process of starting the sexual abuse treatment groups, Miss B. got impatient and set up the Kappa groups herself without waiting for the higher-ups to do their job. But D.B. said he "let himself get sucked into the idea" that he needed to respond right away. Since I was available, he sent me over to help Miss B. He didn't tell her much about me or explain fully what I was to do. He said he wishes he had introduced us and explained all that, because it could have prevented some of the misunderstandings that occurred. But I don't know that it would have helped much, because I still would have spoken up in the group if I saw something I didn't think was fair.

I asked D.B. what his responsibility is to make sure the group leaders are qualified. He said that since Miss B. is a counselor-in-training she can lead groups or start groups as she sees necessary. His responsibility is to investigate complaints or problems, and make any necessary changes. As far as I can tell, he did a good job of carrying out this function. He stepped right in and mediated the matter with Miss B. and me. He said he doesn't like to take sides, saying one person is right and the other is wrong, since they ultimately have to get along and work together. I agree, because I tend not to see situations as black and white, either. I generally believe that both parties in an argument are partly right.

I asked him why S.F. and Miss B. have different views about how to run a victims' group, and why there is no specific treatment plan that all the counselors can follow. He explained that Miss B.'s method may not be perfect, but it is similar to the treatment model that adult correctional institutions use. The adult offender model encourages forced disclosure, or what D.B. called the owning up model. The idea is that the offender must acknowledge and take responsibility for his sexual crimes, even if he has to be forced to do so. But D.B. said that he objects to this approach for treating teenagers because they have other problems like substance abuse, various DSM-III diagnoses, and just the fact they are teenagers.

I asked him what he thinks of forced disclosure. He said he feels uneasy with the method, because it's like re-victimizing the kids—forcing them to relive the abuse as they talk about it in groups. He said he struggles with the re-victimization issue constantly, but because it is widely used and accepted in institutions, many counselors use it with the [Juvenile Correctional Facility] students.

D.B. said he justifies the force method in his own mind because [Juvenile Correctional Facility] is one of the last stops for teenage sex offenders. Thus, the kids are there because gentler methods haven't worked. However, D.B. also admits that if there were more community resources available, such as group homes, many of the sex offenders would not need to be in [Juvenile Correctional Facility].

He said the reason there is no specific treatment plan for [Juvenile Correctional Facility] students is that he still hasn't found a method developed specifically for adolescents. In other words, the [Juvenile Correctional Facility] sexual abuse treatment program is in transition. There is a 500-page treatment manual, which D.B. compiled from relevant literature, but it is no longer used. He originally wrote it as a resource for counselors when the sexual abuse program was based on a psycho-educational model. Now that the program is more treatment oriented, counselors have to make up discussion topics and activities as they go along. I think this places an unreasonable burden on line staff, who may not have a background in counseling techniques. I feel that if someone provided the staff with an easy-to-follow, structured plan, it would substantially raise the level of therapy for all [Juvenile Correctional Facility] students.

Next quarter, when I start my field study, I am going to ask D.B. if I can work with him to develop such a treatment plan. This will require extensive research, but I have done a preliminary literature search at the library. Without completing the research, it is hard to say what the scope of the program would be. However, if the program were to include art therapy, I would use some of the following techniques.

The first week I would have students do a spontaneous drawing and then share it with the group. I would also do a genogram and ask each student to explain the basic relationships in his family. A genogram is similar to a family tree, but is used for assessment purposes. It shows the client's family members, drafted out in chart form (McGoldrick & Gerson, 1985). The second week I would talk about anger and have the students draw a picture that expresses their anger. Then we would talk about the drawings and talk about anger in general. Then, if the students felt ready, I would ask them to disclose more details about their abuse and/or sex offenses by identifying the details on their genograms from the previous week.

I realize that disclosure is important, but I would not ask the students to disclose before they are ready. To this end, the first few meetings might concentrate on building a safe atmosphere in the group.

An Alternative Treatment Program

On Nov. 21, Eric Lichtenthaler of the Morrison Center spoke in one of my classes. He leads the Responsible Adolescent and Parent Program, a sex offender treatment program in Portland, Oregon. This is an outpatient program that treats adjudicated adolescents who have been convicted of sex offenses. Morrison Center usually gets their clients as a condition of parole, but they only accept juveniles if their family is willing to participate in treatment. They use a systemic treatment program, which means they treat the whole family instead of just the offender.

I told Eric what I had seen at [Juvenile Correctional Facility] and asked him if he ever forces his clients to disclose. He said that since the goal is to get the sex offender to take responsibility for his behavior, disclosure is an important element in the treatment. However, he emphasized that it can be a form of violence to force the offender to disclose before he's ready. He said, "Violence is forcing someone to do something they don't want to do," and, "Forced change violates boundaries and is offensive." He said that all disclosure must be done in an atmosphere of trust. Thus, his program focuses on Joining" and "Readiness." Joining refers to the process of making each client feel like part of the group. Readiness means creating a sense of trust and security.

I asked Eric if I could sit in on some of his meetings in December, after finals. He said he would be glad to have me visit and even mentioned that they will be looking for practicum students in January. I can't wait to see what they do at the Morrison Center. I may even decide to do my field study there, instead of [Juvenile Correctional Facility]. They treat the same population—juvenile delinquents—and even get clients who have just come out of [Juvenile Correctional Facility]. I may decide to stay at [Juvenile Correctional Facility], but I am anxious to see what a more functional, more therapeutic program is like. I am glad I met Eric Lichtenthaler and had a chance to hear him speak.

Conclusions

My experience so far has confirmed my original, prejudicial expectation: [Juvenile Correctional Facility] is a somewhat dysfunctional place where kids don't get the best therapeutic treatment. It's unfortunate I see it like that, but I'm not out to change the whole system. The best I can do is try to keep an objective view and not let it mesmerize me into complacency.

D.B. is the person responsible for the way sex offender treatment is carried out. Unfortunately, he has little or no influence on budget and personnel decisions. D.B. can make suggestions and try to intervene when there's a problem, but that's not the same as a cure. Getting qualified personnel is his biggest complaint, and with recent constrictions on the State budget, it doesn't look like there's any relief in sight.

On the other hand, Morrison Center supports itself through public and private grants, as well as third-party payments (insurance). Also, it is privately owned and operated. Therefore, the directors can hire whomever they want and run the program any way they want to run it. They have chosen to begin their treatment process with a period of joining and readiness. In my opinion, such a foundation is sure to bring more positive and lasting results.

While there is little I can do about [Juvenile Correctional Facility], I am glad to have the opportunity to observe it. I ultimately want to work with adolescents, especially juvenile delinquents, so I have to be aware of what it is like for them when they are incarcerated in places like [Juvenile Correctional Facility]. I also think it will be valuable for me to find out more about the Morrison Program. That way I can compare institutional and non-institutional treatment and have a better perspective on the whole field.

References

Bucklin, D.A. & Muster, N.J. (1990). Taped interview (audio cassette). Salem, OR: unpublished.

Kratcoski, P.C. (1989). Group counseling in corrections. In P.C. Kratcoski (Ed.), Correctional counseling and treatment, 2nd ed. (pp. 269-276). Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.

Brown, B.S., Wienckowski, L.A., & Stolz, S.B. (1989). Behavior modification: Perspective on a current issue. In P.C. Kratcoski (Ed.), Correctional counseling and treatment, 2nd ed. (pp. 200-244). Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.

McGoldrick, M. & Gerson, R. (1985). Genograms in family assessment. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Trotzer, J.P. (1989). The process of group counseling. In P.C. Kratcoski (Ed.), Correctional counseling and treatment, 2nd ed. (pp. 277-303). Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.

The Impact of Family Violence on Shaping Delinquent Behavior

The Connection

Assassins such as Arthur Bremer, Sirhan Sirhan, James Earl Ray, Lee Harvey Oswald, and John Wilkes Booth were all products of abusive households (Thornton, Voigt, & Doerner, 1987). Many professionals agree that family violence can have lasting effects on an individual, ranging from general insecurity to severe criminal disorders (for example, Gelles & Cornell, 1985; Straus, 1988; Thornton et al.). Family violence comes in many forms—violence between adults in the household, adults' physical or sexual abuse toward children, and even children's abuse of adults. In this review, I attempt to compile information specifically about the causal relationship between adult-to-child violence and the child's later juvenile delinquency.

The cycle of family violence to juvenile delinquency has been the subject of much empirical research, especially over the last decade. Despite the research and despite the opinions of professionals in the field who believe there is a connection, scholars are reluctant to declare any definitive link between family violence and juvenile delinquency (Thornton et al.; Koski, 1988).

Even though there is no clinical diagnosis for a juvenile-victim personality disorder, research shows that significant numbers of juvenile offenders are victims first, before they become criminals (Burgess, Hartman, McCormack, and Grant, 1988; Farber, Kinast, McCoard, and Falkner, 1984; Paperny and Deisher, 1983; Rosenbaum, 1989). One study (Lewis, Pincus, Lovely, Spitzer, & Moy, 1987) even goes so far as to suggest adding a new category to the DSM-III-R to describe individuals who fit the victim-to-victimizer syndrome.

To gather data for this theory, some researchers analyzed individual delinquents (Burgess et al.; Wallerstein & Blakeslee,1988), while others studied populations of inmates in juvenile institutions (Farber et al.; Lewis et al.; Rosenbaum). One group of researchers (Dembo, Dertke et al., 1988; Dembo, Washburn et al., 1987; Dembo, Williams et al., 1988; Dembo, Williams et al., 1989) studied inmates at juvenile detention centers to see if family violence had an effect on inmates' drug use. Other researchers have focused on family violence leading to violent crimes (Paperny and Deisher) and runaway (Farber and Kinast; Rosenbaum). Some authors present an overview of the problem in their writing by incorporating information from many sources (Gelles & Cornell; Straus; Thornton et al.; Wallerstein & Blakeslee).

The earliest study I could locate was a definitive report (Carr, 1977) analyzing juveniles in New York state, submitted to the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Also at that time, the University of Washington held a symposium on child abuse and its influence on juvenile delinquency. The symposium was called, "Exploring the Relationship Between Child Abuse and Delinquency." I was unable to locate a paper from that symposium called, "Report on the Relationship Between Child Abuse and Neglect and Later Socially Deviant Behavior," by Alfaro. But I did find a book with the same name as the symposium (Hunner & Walker, 1981), containing a chapter by Alfaro bearing the same name as the paper he presented at the symposium. The book contains 19 articles linking family violence to delinquent behavior. The associate chief of the Children's Bureau, Office of Child Development, Department of Health, Education, and Welfare wrote the book's foreword. By his account, the government department had been debating this issue since 1970. The book's editors made no mention of the University of Washington symposium, but I suspect that many of the 19 articles came from the symposium.

Although some scholars are reluctant to declare a causal relationship between family violence and later delinquent behavior, it seems there is already substantial data available on the subject. As one professional in the field (Jensen, 1990) said, "We have to see the [delinquent] as a victim. Until we, as professionals, stop treating the symptoms and start looking behind the scenes and saying, 'What is going on in this family?', we can't do a good job."

Even if the research is not one hundred percent conclusive, I believe juvenile delinquency can be reduced by addressing the problem of family violence. Researchers at Utah State University (Lee & Goddard, 1989) are working on a family education program that may be helpful in this regard. The program, called Family Connections, is based on two principles. First, it teaches families to recognize their strengths and become responsible for their own well-being. Second, it teaches them to develop communication skills they do not already have. Overall, the program is designed to reinforce each family member's sense of worth and happiness. While educational programs like Family Connections are only in the experimental stages, this could prove a viable approach to breaking the cycle of family violence to delinquency.

References

Burgess, A.W., Hartman, C.R., McCormack, A. & Grant, C.A. (1988). Child victim to juvenile victimizer: Treatment implications. International Journal of Family Psychiatry, Vol. 9, No. 4, 403-416.

Carr, A. (1977). Final report on analysis of child maltreatment—juvenile misconduct association in eight New York counties. Report to the National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect, Office of Human Development Services, Department of Health, Education and Welfare. Eric document ED 180 157.

Dembo, R.M., Dertke, M., Williams, L., Wish, E.D., Berry, E., Getreu, A., Washburn, M., & Schmeidler, J. (1988). The relationship between physical and sexual abuse and illicit drug use: A replication among a new sample of youths entering a juvenile detention center. International Journal of the Addictions, Vol. 23, No. 4, 351-378.

Dembo, R.M., Washburn, M., Wish, E.D., Schmeidler, J., Getreu, A., Berry, E., Williams, L. & Blount, W.R. (1987). Further examination of the association between heavy marijuana use and crime among youths entering a juvenile detention center. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, Vol. 19, No. 4, 361-373.

Dembo, R.M., Williams, L, Berry, E., Getreu, A., Wish, E.D., Dertke, M, & Schmeidler, J. (1988). The relationship between physical and sexual abuse and illicit drug use: A replication among a new sample of youths entering a juvenile detention center. International Journal of the Addictions, Vol 23, No. 11, 1101-1123.

Dembo, R.M., Williams, L., La Voie, L., Berry, E., Getreu, A., Wish, E.D., Schmeidler, J., & Washburn, M. (1989). Physical abuse, sexual victimization, and illicit drug use: Replication of a structural analysis among a new sample of high-risk youths. Violence and Victims, Vol. 4, No. 2, 121-138.

Farber, E.D., Kinast, C., McCoard, W.D., & Falkner, D. (1984). Violence in families of adolescent runaways. Child Abuse and Neglect, Vol. 8, 295-299.

Gelles, R.J. & Cornell, C.P. (1985). Intimate violence in families. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Hunner, R.J. & Walker, Y.E. (1981). Exploring the relationship between child abuse and delinquency. Montclair, NJ: Allanheld, Osman.

Jensen, D. (Interviewee). (1990). Taped telephone interview between Donna Jensen and Nori Muster. Salem, OR. (Unpublished).

Koski, P.R. (1988). Family violence and nonfamily deviance: Taking stock of the literature. Marriage and Family Review, Vol. 12, No. 1-2, 23-46.

Lee, T.R. & Goddard, H.W. (1989). Developing family relationship skills to prevent substance abuse among high-risk youth. Family Relations, Vol. 38, 301-305.

Lewis, D.O., Pincus, J.H., Lovely, R., Spitzer, E., & Moy, E. (1987). Biopsychosocial characteristics of matched samples of delinquents and nondelinquents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Vol. 26, No. 5, 744-752.

Paperny, D., & Deisher, R.W. (1983). Maltreatment of adolescents: The relationship to a predisposition toward violent behavior and delinquency. Adolescence, Vol. 18, No. 71, 499-506.