Presented by: Nori J. Muster,

a candidate for the degree of

Masters of Science in Interdisciplinary Studies, 1991

Introduction

Sexual child abuse is a growing problem in our society. A 1985 Los Angeles Times survey estimated that nearly 38 million adults in America were sexually abused as children (cited in Engel, 1989). Statistics show that one in three women and one in seven men are sexually abused by the time they reach the age of 18 (Cooney, 1987; Giarretto, 1982).

Through the 1960s and 1970s, most people thought child molesters were "trench-coated strangers" (Cooney, 1987; Lew, 1988). However, research reveals that eight out of 10 child victims are abused by someone they know and trust, including parents, step-parents, cousins, aunts, uncles, grandparents, teachers, baby-sitters, and older children in the neighborhood (Cooney; Daugherty, 1984). The trauma of sexual child abuse can range from antisocial aggression at one extreme, to withdrawal, depression, and multiple personality disorder (MPD) at the other (Calof, 1988a; Cohen & Phelps, 1985; Cooney; Daugherty), depending on whether the victim turns the rage outward or inward.

While children may react to sexual abuse in a variety of ways, one common response is that abused children may become "sexually reactive" (J. Littlebury, personal communication, February 3, 1991). That is, they may touch or grab playmates and adults, mimic sex play on younger children (sometimes to the point of penetration), masturbate inappropriately, abuse animals, and use sexual words to antagonize adults. They may also begin to have sexual girlfriend/boyfriend-like relationships as early as nine or ten years of age.

Sexual acting out happens for several reasons. According to Engel (1989), a child is not emotionally or physically equipped to handle sexual contact at an early age. The child's aggressive sex play may be an attempt to deal with the reality of the abusive experience. Second, sex may become an outlet for the child's pain, hurt, and anger. There is also the danger that a sexually reactive child may grow into an adult child molester, rapist, or pedophile.

Many studies cite a relationship between childhood abuse and later deviant behavior (Abbey, 1987; Burgess, Hartman, McCormack, & Grant, 1988; Dembo, et al., 1989). But the correlation can be very high or very low, depending on the study. Definitions of "abuse," as well as the study's methodology, may have an influence on results. For example, self-report studies, based on offenders' recollections, tend to show much more childhood abuse than studies based on official records.

Even if they recognize a high correlation, experts disagree on how much an offender's current behavior can be blamed on his childhood experiences. On one side are those who say that deviant behavior is a direct result of an abusive family history (for example, Abbey, 1987; Forward & Buck, 1978); others argue that offenders only use their background to manipulate therapists into excusing their behavior (for example, French, 1988; Stevenson, Castillo, & Sefarbi, 1989). Although experts disagree on statistics, most concede that there are special treatment implications for the victim-turned-perpetrator (Burgess, Hartman, McCormack, & Grant, 1988).

While young children have a better prognosis, treating any sexual aggressor is difficult. According to Engel, "With rare exception, most aggressors do not admit their responsibility for the sexual abuse. Denial is the most common reaction" (1989, p. 47). In the course of her analysis, Engel explains the prescribed treatment: "The molester must admit the gravity of his offense and let down his armor of rationalization. Then he must work on his problem every day for the rest of his life, much like a recovered alcoholic."

If, as Engel asserts, offenders are resistant to treatment, it poses a challenge to find a therapy that will make them want to work on their problems every day for the rest of their lives. This is especially true in the case of mandated clients, who have been sentenced to a treatment program. Chances of success are higher if the client feels an internal motivation to change.

The purpose of this study is to propose an alternative treatment design that will motivate juvenile sex offenders to want to work on their sex abuse and sex offense related problems. The design will be implemented with a sample of juvenile sex offenders and then it will be evaluated by therapists who work in the field of sexual abuse and sex offender treatment. Implications of the alternative treatment design will be discussed in light of the evaluation.

To understand the proposed treatment design, several related issues will be reviewed: traditional sex offender treatment and the theories behind it, and alternative therapies, like art therapy and non-confrontational, client-centered therapy.

As sexual abuse becomes a prominent social problem, numerous researchers have proposed treatment designs (Blake-White & Kline, 1985; Calof, 1988b; Carozza & Heirsteiner, 1982; Davis, 1990; Engel, 1989; and Powell & Faherty, 1990). Although there are no universally accepted treatment designs, the literature generally supports a sympathetic approach to therapy (Davis; Engel; Forward & Buck, 1978; Gil, 1983; Lew, 1988). Gil explains, "Denial helps block out unpleasant, painful memories. Children who are abused build a protective wall of denial which helps to keep them safe from the pain they expect or experience. . . . It's important to lower the wall slowly" (pp. 12-13). Davis, another self-help author, devotes the first section of her workbook to topics like privacy, support systems, and suicide prevention plans (pp. 15-110).

Therapists try to lower the wall slowly for child victims, even if they are sexually reactive. According to one researcher (D. Calof, personal communication, January 11, 1991), the sexually abused child is an object of society's pity--to be "hugged into a cure." However, once the abused child becomes a teenager, treatment may not be gradual or gentle--especially if he acts out sexually. If the child victim becomes a teenage perpetrator, Calof explains, society wants to "shame him into a cure." The juvenile sex offender becomes an object of repulsion, when held up to adult standards. As with the adult perpetrator, "We see him as a monster instead of as a disturbed individual who needs help" (Forward & Buck, 1978, p. 16).

This attitude is reflected in the legal system. Child victims of sexual abuse in Oregon, for example, may be referred to the Childrens Services Division (CSD), public or private treatment centers, or other social service agencies. But once they reach 12 years of age, if they act out sexually, children go before the juvenile court to be judged delinquent (Carr, 1977). Convicted of their sexual behavior, young teenagers are frequently committed to residential treatment programs, juvenile training schools, work camps, and in rare circumstances, even adult jails (Chesney-Lind, 1988). The child who acts out aggressively thus makes the legal transition from abuse victim to juvenile sex offender, and any treatment for his victimization takes place in the context of treating his criminal sexual acts. This may happen even if the juvenile never received treatment for acts perpetrated against him (Carr, 1977).

Some therapists see juvenile sex offenders as abused children who never received adequate treatment. Calof (1988a, 1988b) maintains that all sexual abuse victims act out in aggressive ways, and thus, there should be no difference in therapeutic treatment for victims and perpetrators. Engel (1989) also supports sympathetic treatment of sexually aggressive adolescents (under 16 years old). She explains that since children have not developed a moral code to deal with sexual perpetration, they should not be held responsible for their deviant behavior. In her writings to abuse survivors, Engel says, "Just as you are not bad because of what someone else did to you (the sexual abuse), you are also not bad because of any sexual and cruel acts you committed as a child as a consequence of the abuse you sustained." Engel adds however, "Remember that you are responsible for the things you have done as an adult, even though they too may have been a consequence of the abuse you sustained" (p. 212-214, original emphasis). She draws a distinction between adolescents and adults because she says adults should have enough knowledge and experience to be responsible for their activities.

Most therapists and researchers would disagree with Calof and Engel, maintaining that all sex offenders, even 10- to 12-year-olds, should be confronted with their deviant acts (French, 1988; J. Littlebury, personal communication, February 3, 1991). The majority of experts would argue that offering sympathy--hugging offenders into a cure--would allow them to rationalize and avoid responsibility for their acts (Borzecki & Wormith, 1987; French, 1988; Stevenson, Castillo, & Sefarbi, 1989). Almost all treatment programs use the "adult model" in treating juvenile sex offenders.

The adult model is confrontational, with the goal of distilling and verifying the offender's guilt. In a study comparing 34 adult sex offender treatment programs in the United States and Canada, researchers found that, "Throughout, the focus of such counseling is on the offender's accepting responsibility for his actions and the understanding of factors that precipitated commission of the offense" (Borzecki & Wormith, 1987). The researchers said they found similar trends in juvenile sex offender treatment programs.

There is little published information about juvenile sex offender treatment. However, therapists in the field are a good source of knowledge about current techniques. One treatment specialist (R.L. Finlayson, personal communication, February 9, 1991) said he begins his juvenile sex offender meetings by having every boy state the name of his victim and the nature of his offense. This weekly disclosure is emotionally painful, but perceived as necessary to make offenders "own up" to what they have done. Finlayson explained further that although the process is painful, its therapeutic value is analogous to lancing a boil to let the poison out, before healing can take place.

Juvenile sex offender treatment falls short of full adult treatment, however, since juveniles rarely undergo psychosurgery-castration, drug therapy ("chemical castration"), aversion therapy, or penile plethysmograph assessment (DeZolt & Kratcoski, 1989). But juvenile correctional institutions and most adolescent out-patient treatment programs follow the philosophy of "owning up," "confrontation," and "responsibility," characteristic of the adult model. This approach is standard in the field.

While some adolescents welcome the opportunity to work out their problems within the framework of the confrontational adult model, some

may not respond well. They may refuse to participate in groups, afraid to disclose their sexual history or any feelings associated with the past. The memories may be extremely shameful and private (Davis, 1990; Engel, 1989). According to Van Ornum and Mordock (1988), these children are "angry and full of rage" because "they must deny the bitterness, resentment, fear, anger, and hatred that they feel" (p. 146).

Correctional institutions may justify using the adult model on juveniles because they are charged with "reforming" the child (Chesney-Lind, 1988; Shelden, Horvath, & Tracy, 1989). Actually, it could be argued that juvenile sex offenders who were abused fall somewhere between an adult sex offender and a child victim of sexual abuse. The juvenile sex offender may be deserving of sympathetic therapy, especially if he was sexually abused and never treated.

It may be detrimental to force resistant adolescents to repeatedly disclose their deviant sexual acts, since their reluctance may indicate a deeper psychological disturbance (Davis, 1990; O'Hare & Taylor, 1983). Often, those juveniles who end up in institutions have a dual diagnosis, with sexual abuse and sexually offensive behavior being the least of their problems (G. Carter, personal communication, April 5, 1991).

Although the goal is to bring the juvenile to the point where he can disclose and take responsibility for his crimes (Engel, 1989), the means should not inflict further violence on the child. In the case of offenders who were previously victims, the therapist should take into account the traumatic experiences and the harm that has been done. According to O'Hare and Taylor, "Control and autonomy are key issues for incest survivors. A controlling therapist is too similar to the incestuous abuser to be helpful" (1983, p. 225). Yet, confrontational therapy is very controlling. The offender is force to confess repeatedly, even though he is not a willing participant in the therapy. O'Hare and Taylor hint at the possibility that much of what passes for "intervention" and "therapy" is inappropriate: "It is unusual to find an incest survivor who has not experienced some sort of inappropriate intervention from therapists" (p. 220). Commenting on improper treatment, Engel said, "It is no small wonder that many victims stop seeking professional help altogether" (1989, p. 22).

For the resistant juvenile sex offender who is also a victim, alternative psychotherapy techniques may be helpful in undoing the damage, done initially by the perpetrator, and later, perhaps, by confrontational therapy. This thesis proposes alternative treatment design that uses sympathetic methods rather than confrontational, correctional methods. Thus, the treatment design makes the juvenile sex offender's previous abuse the major consideration. The first phase in the treatment design focuses on building trust, as is done in many sexual abuse treatment designs (Davis, 1990; Engel, 1989; and Powell & Faherty, 1990; Winton, 1987).

The alternative treatment design will address the long-term symptoms of sexual child abuse: damage to self-esteem and self-image; problems with relationships, sexuality and sexual identity; and emotional problems (elaborated in Engel, 1989, pp. 25-32). And the goals of the sex offender design will coincide with the goals of sexual abuse treatment, for example, trust building, giving a sense of safety and security, and helping the client recognize and validate his own feelings (Winton, 1987).

Although there are a variety of alternative therapy methods that are basically non-confrontational, art therapy has been chosen as the primary method in this study. It is the first choice because, historically, the technique evolved as a non-confrontational alternative within the humanistic school of psychology. Art therapy also lends itself well to the special problems of adolescence, sexual abuse, and resistant clients, as will be explained in the following sections.

Most art therapists follow the non-directive philosophy developed by Axline in the 1940s. In non-directive therapy, the client takes the lead in his own healing (Axline, 1947; Axline 1964). Some art therapists prefer more structure in their sessions, but Axline's book, Play Therapy, written 44 years ago, remains a standard text in art therapy education. Axline's method is based on the writings of Carl Rogers. She says,

Non-directive counseling is really more than a technique. It is a basic philosophy of human capacities which stresses the ability within the individual to be self-directive. It is an experience which involves two persons and which gives unity of purpose to the one who is seeking help. (1947, p. 26)

Acceptance and permissiveness are emphasized in Axline's non-directive philosophy, and are demonstrated in the therapist's confidence in her client. She explains that as a child is exploring the toys in the play therapy room, the therapist should never attempt to rush through therapy or do anything that implies a lack of confidence in the child. Rather, the therapist tries to create a safe atmosphere so the child will feel free to share their inner world (p. 63).

Axline enumerates eight basic principles of play therapy (see Appendix A), which speak of the client-centered nature of her technique. One principle is that the therapist accepts the child exactly as he or she is. Another principle is that the therapist's role is to establish a feeling of trust and permissiveness in the relationship so that the child feels free to express his feelings completely (1947). Axline's philosophy may seem out of place in a treatment design for juvenile sex offenders, who are usually considered to be criminals. But the purpose of this study is to approach the clients as victims of sexual abuse, who became perpetrators as a result of their abusive experiences. Thus, it is proposed that a non-directive, sympathetic treatment will have a positive effect on the client's desire to work on their own problems.

As Axline explains, "These attitudes are based upon a philosophy of human relationships which stresses the importance of the individual as a capable, dependable human being who can be entrusted with the responsibility for himself" (1947, p. 62).

According to one researcher (Wolf, 1975) art therapy is "less threatening than a more traditional psychotherapy session" (p. 266), and has been shown to help resistant adolescents. Wolf, an art therapist at a New York alternative school for young adolescents who are not succeeding in public schools, documents his work with "Frank," a disturbed adolescent. In the course of treatment, Frank's behavior improves as he begins to develop a sense of pride and accomplishment in his artwork. Frank learns to build friendships as he begins to "see himself as a person 'worthy' of good things" (p. 264). Wolf concludes that art therapy can be used "successfully with adolescents who are quite naturally going through a period of tremendous mood swings and ambivalence" (p. 266).

Another study (Powell & Faherty, 1990) recommends art therapy in the treatment of sexual abuse victims. Art therapy, the researchers explain, is "designed to slowly introduce members to the co-leaders, to each other, and to their new environment" (p. 36). The study concludes that "communication through the creative arts therapies is now seen by many in the mental health field as the most appropriate and least stressful way to assess and treat the sexually abused child" (p. 36).

Art therapy has its roots in the psychoanalytic/psychiatric movement of Freud and Jung (Wadeson, 1980). Freud developed the concept of the unconscious and dream symbolism, and Jung postulated a collective unconscious with universal symbols (Crain, 1985; Wadeson, 1980). Although neither of these men used art in their work, both placed a great emphasis on symbols and unwittingly laid the groundwork for art therapy. Some therapists were experimenting with art therapy in the 1920s and 1930s (Rubin, 1986), but it was not until the 1940s that art therapy emerged as a therapeutic modality (Axline, 1947; Buck & Hammer, 1969; Rhyne, 1984; Wadeson). One of the first practitioners, Margaret Naumburg, relied heavily on psychoanalytic theory and practice. She would ask clients to draw spontaneously and then interpret their pictures through free association.

Helped by the mid-century Human Potential Movement, art therapy is now used by humanistic, gestalt, behavioral, cognitive, developmental, and family therapists (Rubin, 1987; Wadeson, 1980). The discipline's certification board, the American Art Therapy Association, founded in 1962, now has thousands of registered members.

One advantage of art therapy is that it allows the client a more holistic medium of communication. Wadeson (1980) explains, "Verbalization is linear communication. First we say one thing, then another. Art expression need not obey the rules of language--grammar, syntax, or logic. It is spatial in nature. There is no time element. In art, relationships occur in space. Sometimes this form of expression more nearly duplicates experience" (p. 11). Thus, through art, the client can express herself in a medium that goes beyond words and behavior (Denny, 1975).

Another advantage is that art therapy leaves the client with a tangible product (Wadeson, 1980). The art, which becomes a visible record of the therapy, can reveal emotional patterns or bring significant insights (Wadeson). A tangible art object may also create a bridge for the resistant client to contact his or her inner self. Wadeson calls this process "objectification" because the client's feelings are externalized in a picture, collage, or sculpture. Wadeson explains, "The art object allows the individual, while separating from the feelings, to recognize their existence. If all goes well, the feelings become owned and integrated as a part of the self. Often this happens within one session. For particularly resistant people, it may take longer" (p. 10).

Wadeson (1980) also notes that the art object adds another dimension to the therapy. Besides the relationship between two people (or between all the people in a group), there is the relationship to the art product. Further, since the art object is an expression of the client's self, "the manner in which the art therapist regards it, handles it, puts it away, and recalls it, becomes extremely important" (p. 38). Thus, the art therapist's job is to help the client move to deeper self-understanding, self-appreciation, and self-disclosure (Denny, 1975).

Indeed, art therapy is fundamentally a process of adding meaning to one's life. Wadeson explains, "The stuff of which the creation is made is deeply personal, often putting one more profoundly in touch with oneself. It is here that understanding is achieved" (Wadeson, 1980, p. 6). The creative process not only taps deeper layers of consciousness, but the world of fantasy, as well. Thus, art therapy allows the client resources that would not be available in an ordinary therapeutic milieu.

Wadeson explains that the client's artistic ability is immaterial and that even the client's most minimal drawing expresses something from the unconscious. In non-directive art therapy, the client is ultimately responsible for interpreting his or her own artwork. The therapist does not impose a particular meaning on the client's piece prematurely (Rhyne, 1984; Wadeson). Then after some time, Wadeson explains, the therapist comes to understand the client's visual imagery. "Art expression is a language, but not a common one. It is unique and not immediately understood. The client is encouraged to tutor the art therapist in its meaning. . . . As a result, it is not a ready-made language that becomes communicated, but a language in process, as the client explores and builds his or her own visual mode of expression (Wadeson, 1980, p. 39).

Emunah (1990) explains why art therapy is especially suited to adolescents. She describes the teenage years as a time of intensity, complexity, and upheaval, when the teen changes mentally, emotionally, and physically. During these naturally turbulent years, Emunah explains, "A form of expression is desperately needed, one which matches the intensity and complexity of their experience, is direct but nonthreatening, is constructive and acceptable. Thus, the creative arts therapies provide the means for the teenager to express the "inner explosiveness of adolescence" (Emunah, 1990, p. 102).

Emunah proposes that through creative arts therapies, "The adolescent achieves a sense of emotional release and catharsis," as well as a "sense of mastery over emotion, which is a primary psychic task of adolescence" (1990, p. 103). The release and mastery come when the adolescent structures and expresses what he or she is feeling through the creation of an art product, or a dramatic or musical piece. Emunah explains, "The adolescent takes hold of inner feelings, impulses, and turmoil--that which usually cannot be articulated, let alone contained--and through his or her own resources gives this inner material aesthetic shape and form. The process of creation thereby strengthens the adolescent ego" (p. 104). This is especially true for adolescents who lacked empathetic parental care as infants. Emunah explains that for these youths, "The artistic product, in conjunction with the therapist's regard for it and for the self it reflects, offers some compensation and reparation for these narcissistic deficits" (p. 104).

Another researcher (Estelle, 1990) explains that creative arts therapy can counteract adolescent alienation. According to Estelle, alienation and creativity are in direct opposition because alienation involves a sense of powerlessness and meaninglessness. Art therapy, by its very nature, helps the adolescent gain a sense of power and make meaning out of his or her experience. Thus, "From a sense of paralysis and fragmentation, the alienated individual may be brought to a greater sense of freedom and individuation" (p. 109). She says that art therapy is beneficial because "in the world of art, one can get past the usual confinements, be they internally or externally induced confinements. . . . Idealism, an important component of adolescent development, which unfortunately is often crushed under the pressures of conformity and acculturation, can be expressed through the creative act" (1990, p. 105).

Thus far, it has been shown that art therapy offers unique opportunities for growth and self-discovery. It has been used with sexual abuse victims (Carozza & Heirsteiner, 1982; Cohen & Phelps, 1985; Davis, 1990; Landgarten, 1987; Naitove, 1987; Powell & Faherty, 1990; Wohl, 1985), adolescents (Estelle, 1990; Emunah, 1990), and acting-out adolescents (Landgarten, 1987; Wohl, 1985; Wolf, 1975). It may have been used with juvenile sex offenders, but few, if any, studies are available on this subject. Art therapy seems to go against the standard method of juvenile sex offender treatment, because it is non-directive and permissive. But it is possible that art therapy--because of its ability to inspire self-discovery and creative awareness--may be shown to motivate resistant juvenile sex offenders to want to work on their problems. The following pages will propose a treatment design using art therapy in conjunction with a non-confrontational therapy to treat juvenile sex offenders.

Non-confrontational art therapy is a viable method to help juvenile sex offenders take responsibility for their sex crimes and make progress toward resolving their sexual abuse and sex offender related problems.

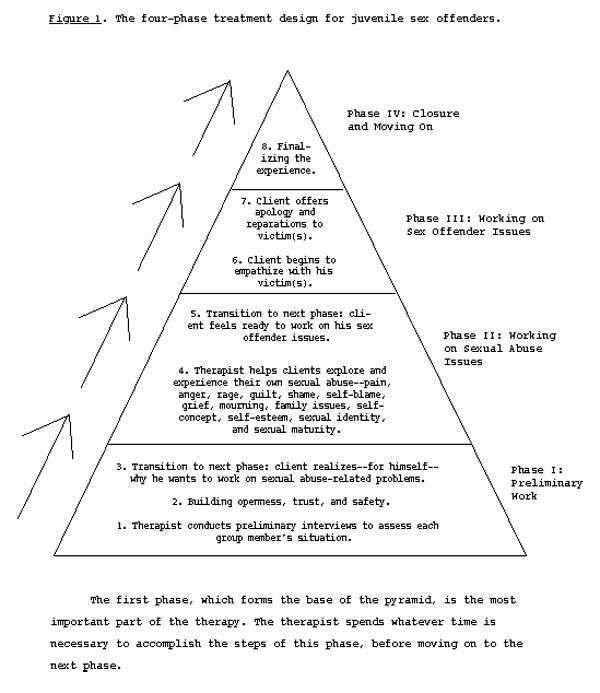

The treatment design (see Figure 1, below) is like a pyramid, where the foundation, Phase I, is the most important part. Phases II, III, and IV are built layer upon layer, once the foundation is firmly established.

Phase I emphasizes trust, because perpetrators (who are victims of sexual abuse) often find it difficult to trust people. The program proposes that when trust is established, the client can begin to see himself as a valuable person, deserving of respect and love. This is important because with low self-esteem, clients may not feel motivated to work on their own problems. They may see no value in helping themselves, or they may be too discouraged to try.

Once the treatment process begins, the client moves through the four phases by a series of "breakthroughs" and "transitions." A breakthrough occurs when the client realizes something important about himself. It may be a realization that he has a good quality, that he has been hurt, or that he feels bad because he has hurt others. When the client has a breakthrough, he may simultaneously make a transition into a new phase of treatment. Two examples of breakthroughs follow.

One day, the researcher led the subjects through a guided visualization exercise where they were asked to think about all the abusive things that have happened to them, all the bad things they have done, and all the people they have hurt. The subjects became absorbed in reviewing their lives, and in the discussion that followed, one subject said, "This is amazing! I just realized that if I'm going to change, it has to come from myself." Another subject said, "I thought about the people I've victimized. I thought about their feelings." In later sessions this second subject repeated that he had been thinking about the people he harmed and felt badly about it. This was a significant breakthrough for this individual, since a psychiatrist had characterized him as "a violent youth with no conception of the suffering he caused for his victims."

The main transitional points are from Phase I to Phase II, and from Phase II to Phase III. They are, "Step 3: Client realizes--for himself--why he wants to work on his own sexual abuse-related problems," and "Step 5: Client feels ready to work on his sex offender issues."

The culmination of the program is at the end of Phase III, "Step 7: Client offers apology and reparations to victim(s)." The act of apologizing to the victim confirms the sex offender's understanding that his acts were wrong, and that he has learned from his mistakes. (The only way to assess the sincerity of this would be in a longitudinal study).

Although the treatment design has no specific time frame, the therapist should allow several weeks to establish a high level of Phase I trust. Subsequent phases take less time, but clients may progress forward into higher phases and then fall back to the trust and safety issues of Phase I. This is common and should not be seen as a backslide. The therapist should allow clients to work on trust issues whenever necessary, without trying to rush the therapy along.

Under ideal circumstances, groups would be formed at the beginning and stay together all the way through treatment, accepting no new members once they begin. In a group where members are transient (as was the case in this study), new people come in at different levels of maturity, with different needs, thus slowing the progress of the others. The therapist must constantly orient new group members to the art therapy process and try to help them become established with the other group members.

Figure 1 gives an overview of the pyramid-like structure of the four-phase treatment design. The following sections describe the treatment phases in more detail.

[Editor's Note: The graphs on these thesis web pages were lifted from old Pagemaker files, therefore the type is somewhat pixelated. We regret any inconvenience this may cause.]

The first phase is the foundation of the treatment design. It is designed to bring the client to a breakthrough where he wants to work on his problems. If this much can be accomplished, then the client may someday finish the work himself (even if he is transferred or released before completing the therapy). Following are the steps of Phase I:

Step 1. Therapist conducts preliminary interviews to assess each group member's situation. The therapist looks for evidence of past sexual abuse that may have contributed to the clients' becoming a sex offender. She can find out how serious the sexual abuse and sex offences were, and whether the client ever received treatment for sexual abuse. She may interview the client, read the client's files, and if possible, interview parole officers, line staff, and relatives.

Sex offenders are often classified according to the severity of their case (Abbey, 1987; Wenet, 1984). If the therapist finds that clients have been categorized, she can note this. However, this step is not meant to be a screening process to exclude difficult-to-treat cases. Rather, the therapist's preparation is meant to familiarize her with the clients' backgrounds and needs.

Step 2. Building openness, trust, and rapport. Once group meetings begin, the therapist's first goal is to build a safe atmosphere. This is an important aspect of the non-confrontational approach. If trust and safety are established in the beginning, then the clients will be more willing to share their feelings and thoughts later on. All sharing should be voluntary for real trust to develop. Therefore, the therapist should not force clients to disclose, or even speak, if they are reluctant. However, clients should take part in drawing exercises, or at least pay attention to group activities and try to participate.

The therapist may begin by asking group members for information about their families. She may sketch a genogram (McGoldrick & Gerson, 1985) to get a clearer idea of the family situation. Talking about the family of origin is an important part of this step because it allows the client to begin sharing something about himself in a non-threatening way.

Step 3. Transition to the next phase: client realizes--for himself--why he wants to work on sexual abuse-related problems. Once trust is established, the next step is to help clients see for themselves why it will be beneficial to work on their sexual abuse-related problems. This is a key phase of the program, since it involves breaking through the clients' minimization and denial of the abuse, as well as his alienation toward peers, therapist, and authority figures in general.

As the client begins to open up, he gradually shares more about himself. As he experiences acceptance from the therapist and other group members, he begins to peel away the layers of anger, embarrassment, fear, guilt, and pain. While lowering his resistance, the client will simultaneously build his sense of self-worth and eventually come to a point where he values himself enough to want to change. The non-confrontational process assumes that the client will eventually see himself as a worthwhile person, and thus want to help himself.

In Phase II, the therapist continues to help group members understand themselves in light of their sexual abuse. The preliminary step of this phase addresses sexual abuse issues in general, while the latter step gradually leads the client to the next phase, where he will address his sex offender problems.

Step 4. Therapist helps clients explore and experience their own sexual abuse--pain, anger, rage, guilt, shame, self-blame, grief, mourning, family issues, self-concept, self-esteem, sexual identity, and sexual maturity. By now, group members and therapist have built trust and the ability to share their feelings through their drawings and discussions. Therefore, the therapist can focus on sexual abuse issues and encourage group members to share specific feelings they have on this subject.

A client entering this stage may benefit from reading books on male sexual abuse like Victims No Longer (Lew, 1988) or The Courage to Heal Workbook (Davis, 1989). These books, and others like them, go into detail about the healing process and may answer the client's questions and concerns.

Adolescence is a difficult time, even for those who have not been sexually abused. Thus, the therapist may also want to address general adolescent issues, like drugs, identity, growing up, and so on.

Step 5. Transition to next phase: client feels ready to work on his sex offender issues. If the client has developed some sensitivity about how he was hurt by having been sexually abused, he may be ready to begin empathizing with his victims. When he has had some breakthroughs in this regard, he will be ready to start the next phase. This is because he has reached a level where he acknowledges the pain of having been abused. As he gets in touch with his past, the numbness of feelings begins to melt. He begins to develop self-esteem and hope for the future. This gives the client a chance to realize that his aggressive sexual behavior is detrimental. Thus, he may decide to begin to resolve these issues.

At this time, the therapist addresses the client's sex offenses--the criminal activities that brought the client into the state's jurisdiction. Because trust and openness are already established in the group, these problems become easier to talk about and therapeutic work can take place. Disclosures will be meaningful, rather than mechanical.

Step 6. Client begins to empathize with his victim(s). The first step of this phase is to help the client understand how his victim(s) felt about being abused. This breaks down the client's minimization and denial of his aggressive behavior because he realizes that his acts were wrong (Engel, 1989; Lew, 1988). Emphasis in this phase will be to help group members develop empathy for their victims and move toward offering apologies and reparations for what they did.

If clients have resolved issues raised in previous phases, they will be ready to address the guilt, shame, confusion, and anger surrounding their aggressive sexual acts. Often, in the case of incest, the sexual aggression is a way of "getting back" at parents, or expressing alienation from the family (Cooney, 1987; Forward & Buck, 1978). Therefore, family issues may emerge during this phase. The therapist will also encounter a great amount of minimization and denial. The next breakthrough occurs when the client has a realization of the severity of his sexual aggression and the harm it has caused to his victims.

Step 7. Client offers apologies and reparations to victim(s). In this step the client writes a letter of apology, which can be shared with the group. When the client feels ready, he may possibly mail the letter to the victim. The client's letter will reflect his degree of sincerity and realization of the harm he has caused. Thus, the letter is the test of the client's achievement in all previous phases of the program.

As the four-phase treatment design progresses into the later stages, art therapy continues to be an important tool. Clients will be accustomed to expressing their feelings on paper. Thus, each session may begin with 10- to 15-minutes of drawing, followed by sharing.

The final phase can apply to the whole group if the time for meetings comes to an end. In this study, however, members of the group left at different times. Either way, formal closure is recommended so the client(s) can finalize the experience and separate from the group.

Step 8. Finalizing the experience. The client learns that after leaving the group, he must continue to work on his grief, anger, and [accountability] associated with his abuse/offender experiences. He must be aware that denial and minimization on his part may lead to reoffending. Further, he must realize that the end of the group does not mean the end of life's challenges; he must continue to cope with the usual stresses of adolescence, and later, adulthood. No matter how much is resolved over the course of therapy, the client must leave with the understanding that his healing will take a lifetime. The therapist can discuss the problems of adolescence and help clients realize what they can expect ahead. Group members can review what they have learned about themselves.

Due to the openness and sharing of the group, emotional bonds may be formed. Therefore, when therapy ends (or, when someone leaves the group), everyone can take the time to say goodbye. Possible exercises for this phase are going-away cards signed by everyone in the group, or a group mural. Members may want to draw "before and after" portraits of themselves (or each other) and discuss the pictures. It may also be a good time to review each client's artwork.

After completing the group experience, individual members will either go to another juvenile facility or back into the community. They may take part in a court-mandated after-care treatment program, or they may not. The decisions are made by the clients' parole officer and the facility's Close Custody Review Board (CCRB). The therapist should find out where each client will be going so she can help the individuals prepare.

To see if this treatment plan was feasible, it was tested with subjects from a sex offender treatment cottage of an Oregon state juvenile training school. The groups were held twice a week, beginning in October 1990. Group meetings lasted one to one-and-a-half hours, with three to six subjects per group. There were some one-to-one sessions. The meetings occurred inside the cottage, at the end of a hallway. (Ideally, meetings could be held in a private room, where interruptions could be kept to a minimum.) Subjects and therapist sat around a table; materials included pencils, erasers, crayons, paper drawing tablets, and magazines (for collage).

While the sample was confined to one cottage of the juvenile facility, the make-up of the groups was in constant flux. Subjects sometimes had to miss group meetings because they were in disciplinary lock-up. Also, the attrition rate was high, due to clients being discharged from the facility or transferred to other cottages. Thus, to keep the groups going, new subjects had to be accepted throughout the study. As mentioned before, this situation was not ideal. The influx of new group members interrupted healthy group process. Nevertheless, many group members had valid breakthroughs.

The participants included 20 boys, aged 12 to 17. At first, cottage line staff chose subjects who were "hard to work with" or "resistant to sexual abuse treatment," and requested that they take part in the art therapy groups. The staff hoped that the alternative format would help resistant subjects communicate. As the groups became known in the cottage, juveniles approached the researcher to be accepted into the group.

Because cottage staff chose subjects for the groups, or subjects volunteered, the researcher did not need to conduct preliminary interviews. However, information was gathered from the subjects' files to present a profile of the group. All group members had been committed to the juvenile training school as a result of their sex offenses, namely first degree sodomy, first degree rape, or first degree sexual abuse. Subjects also had other offenses, such as menacing, burglary, malicious mischief, unauthorized use of a vehicle, arson, runaway, and so on.

Besides criminal charges, subjects' records revealed emotional problems like identity disorder, dysthymia, pervasive developmental disorder, explosive disorder, learning disabilities, borderline intellectual functioning, inappropriate affect, adjustment disorder, attention deficit, and gender identity disorder of adolescence.

Most subjects had received clinical diagnoses of "conduct disorder" of various types and degrees, i.e. "depression, possible underlying organic, neurological factors," "solitary, aggressive type, moderate to severe," "undifferentiated type," and "solitary, aggressive type, severe" (see American Psychiatric Association, 1987, DSM-III-R).

Other comments indicate the severity of subjects' disorders: "Shows no control or internal monitoring over his behavior. Method of coping is to shut off feelings and act out negatively," "Threat to the community, lack of remorse, likely to reoffend," "Undersocialized exploiter of younger children," "Quite severely emotionally disturbed. . . . Most likely, the direction his problem will take will be as a schizoid or paranoid personality," and "Predatory sexual offender who is untreatable and who will need to be locked up for years to come. Extremely poor prognosis."

Subjects generally came from chaotic families in which there was only one parent, or where adults in the household were drug-addicted. Many came from families where intergenerational incest was prevalent. Few subjects had traditional, two-parent families. Most had multiple stepparents and step-siblings, and their families had been repeatedly split apart by divorce and desertion.

Nineteen of the 20 subjects had documented sexual abuse in their files. The other boy revealed in group that he suspected sexual abuse and that his father had introduced him to pornography. Examples of documented abusive acts are as follows: "Father forced [subject] to have intercourse with dogs, supplied marijuana to [subject] since age two; [subject] suffered from mother's physically abusive boyfriend," "Victim of a 16- to 17-year-old baby-sitter when eight years old. . . . Parents were never married; sparse contact with father," "Sexually abused by [mentally disabled] relative at age five. Sexually abused by a cousin when 11," "Sexually abused by mother's boyfriend. Also physically abused by father," and "Stepfather keeps pornography, has given it to [subject]."

Examples of the sex crimes committed by subjects are as follows: "Sexually abused seven-year-old sister, caught and beaten by father; previous incidents in 1988, same victim," "Molested niece, aged four; anal, oral, vaginal penetration; threatened victim with a gun," "Exposed himself and masturbated in front of younger brother," "Sexually aggressive toward peers, molested a boy while on the run from [Oregon boys home]," "Sexually victimized children of older brother's girlfriend," "Excessive and inappropriate masturbation, sexual talk, and voyeurism. Child's sexual contacts have been with a number of neighborhood peers, as well as 50 contacts with younger sister," "Sexually offended eight-year-old half-sister," "Sodomized six-year-old boy," and "Raped two females, aged six and eight; also caught fondling another boy."

Subjects came into contact with the law when their victims reported them to the authorities, or when parents or other adults discovered their aggressive sexual behavior. When the group started, some of the subjects had been in the juvenile facility for less than a month, while others had served a year or more. Some subjects became wards of the state at an early age, being shifted from foster home, to boys home, to work camp, back to a foster home, and so on. Many of the subjects had been through traditional sex offender treatment (described above).

All subjects were involved in the institution's sex offender treatment program, which included writing in a workbook and being graded on behavior through a behavior-modification points system. The institutional treatment method is based on Guided Group Interaction (GGI), a peer-culture group therapy milieu. GGI originated in the 1940s, post-World War II era in America. The basis of GGI is to create a group atmosphere where each member helps the others work toward their rehabilitation goals (Kratcoski, 1989; Trotzer, 1989). It is a precursor to Positive Peer Culture (PPC), where the peer group supports positive change. According to Kratcoski, "The key element of guided group interaction is the problem-solving activity that takes place in the group meetings" (p. 270).

The four-phase treatment design was carried out in the context of the institution's regular sex offender treatment program. Thus, it was used in addition to an already-existing program. Although the researcher felt there were inherent drawbacks in the institution's treatment design, there were advantages as well. For one thing, the strict atmosphere automatically set limits on behavior, so subjects were able to participate in the less structured group without losing control or becoming violent. An advantage of the positive peer milieu was that subjects encouraged each other to cooperate and take advantage of the art therapy group.

Implementing the four-phase treatment design is not dependent upon specific activities. Rather, the therapist can use any activities that facilitate the client's movement through the phases. Art therapy is not a "bag of tricks" the therapist pulls out to cure her clients (Wadeson, 1989). The therapist must be sensitive to group members to know when a particular exercise will be beneficial. As Denny (1975) explains, "The choice and timing of an approach should always depend upon the client or group, who themselves will provide the clues. A predetermined program of techniques is usually to be avoided" (p. 148).

The technique categories described below are not intended to set a rigid format. Rather, they are suggestions to draw upon if they suit group members' needs at the time. As Denny (1975) explains, "Fascination with a particular technique should never be allowed to dictate its use" (p. 148). Thus it is up to the therapist to decide upon the specific activities in any given session. According to Axline (1947), "It takes steadiness, sensitivity, and resourcefulness on the part of the therapist to keep the therapy alive" (p. 65).

No matter what activities are selected, the goal is to encourage the group members to draw pictures and talk about their feelings. The artistic quality of the art product is not important, since the goal is self-revelation, not fine art. The therapist's role is to help each group member see himself as he really is, since this will lead to breakthroughs.

The therapist must be aware of each client's level of advancement to know how to proceed. Group members may progress at different rates, so various phases of the process may take place simultaneously in the same group. The therapist must try to keep the group on track, while encouraging each client to develop at his own pace. It is an individual process.

With this preface in mind, some of the art therapy activities used in this study are listed in Appendix B. Any of the activities can be applied at any phase in the program, but specific activities within the categories lend themselves to specific phases. For example, in the beginning phases, the therapist may ask group members to draw self-portraits and talk about how they see themselves. In the latter phases, the therapist may ask group members to draw pictures of their feelings about their sexual abuse victimization and sexual aggression.

The results of the pilot study, including case vignettes illustrating breakthrough points, are included in Appendix C.

Looking at case vignettes during this trial run is one way to evaluate the four-phase treatment program. In the case of Donny, the first case discussed in Appendix C, the subject is an unusually disturbed individual. Doctors and other examiners gave him a very poor prognosis. But the art therapy group helped Donny express some of his violent feelings. This may have helped him resolve some of the underlying conflict.

Joel (the second case discussed in Appendix C) also said he felt he had made progress. One of the activities helped Joel understand the amount of subconscious anger and confusion he felt toward his father. He returned to the issues surrounding his father in subsequent groups, leading to further breakthroughs in this area.

Graduate students are welcome to replicate my study, but if you use my materials or quote from my thesis, I ask that you acknowledge my contribution to your work. Please cite me as follows in your references: "Nori Muster, author of A Four-Phase Treatment Design for Juvenile Sex Offenders, Western Oregon University, 1991."

more graduate work

Index