Presented by: Nori J. Muster,

a candidate for the degree of

Masters of Science in Interdisciplinary Studies, 1991

Other Comments

In addition to the short-answer and multiple-choice questions, respondents had the option of writing something about the four-phase treatment design. Some therapists made neutral comments or suggestions, for example, the sexual abuse treatment coordinator at the facility where this study took place said, "Plan as indicated should be holistic and address issues such as substance abuse (self/family), physical, emotional abuse, loss, neglect, etc."

Other respondents offered support for the design. The sexual abuse treatment coordinator at another Oregon training school said,

This type of approach was used for several years by myself and [another therapist] at Oregon State Hospital. Depending on the assessment and extent of abuse, both as victim and as offender, Phase II and III were interchangeable, occasionally simultaneous. It also involved normal sex education, socialization, and day-to-day living situations.

One respondent defended the anti-sympathetic philosophy that portrays juvenile sex offenders as criminals who need confrontational therapy to "own up" to their criminal acts. The person who made this defense is a treatment coordinator at a state-run youth and family treatment unit in southern Oregon. He said,

Offenders cannot process their own abuse effectively prior to taking a basic level of responsibility and accountability for their acts. They will tend to feed their cognitive distortions with their misperceptions of the victim therapy experience. They tend to not process their own victimization completely enough (surface treatment) without allowing the emotional content to be explored honestly.

Several respondents had questions about the mechanics of the four-phase treatment program, due to the brevity of the explanation in the survey packet. For example, one therapist asked how clients make the transition from stage to stage. Another therapist said,

Since sex offenders are mandated by law to address their issues, it seems artificial to state that they can wait until they "feel" like it. Where does the therapist's responsibility for preventing further abuse [by the sex offender] come in?

Overall, comments were positive, supportive, and helpful. Respondents also mentioned various theoretical frameworks they've used, including gestalt, holistic, feminist, eclectic, social skills building, psychodrama, transactional analysis, Rogerian, family systems, hypnotherapy, and so on.

Special Survey Questions

As mentioned above, special survey questions were distributed to four staff members at the juvenile training school where the pilot study took place. Only one special survey was returned. The respondent wrote, "The groups have fit well . . . and added to the variety of positive experiences to which we try to expose our students. The students who participated looked forward to being in the groups and usually seemed engrossed in what was being done. Students who took part seemed to get along with each other during the group session. This is an important step for them, since it is usually a problem at most other times."

Discussion

The therapists in this study generally supported non-confrontational art therapy as a viable method to help juvenile sex offenders. Favorable comments about the four-phase treatment design far outweighed unfavorable comments (see Figure 8 and comments section above) and 72% of the respondents said art therapy could be useful with juvenile sex offenders (see Figure 7).

Respondents also portrayed themselves as generally open minded about the direction of therapy. They did not hold fast to the theory that offender issues must be addressed first, as evinced by the strong support for "simultaneous" and "flexible" approaches with all three age categories (see Figure 4). Given a choice of which issues to address first with juvenile sex offenders, more therapists chose victim issues over offender issues (28% compared to 17%).

The respondents did not attribute significant credibility to the notion that sympathetic forms of therapy tend to reinforce minimization and denial. In the questions dealing with this issue, neither viewpoint had a majority in regard to juveniles (33% to 33%, see Figure 3). With adults, therapists seemed even less likely to support the "minimization and denial" contention (33% pro-sympathetic; 28% anti-sympathetic).

The data from these two questions supports a flexible approach and appears neutral on the question of minimization and denial. This contradicts the prevailing belief that most therapists belong to the "owning up" school of offender treatment. Half of the respondents didn't even cast a vote for pro-sympathetic or anti-sympathetic treatment with juveniles, showing that they may have no strong opinion on the subject.

Who Says "Offender Issues Should be Dealt With First"?

In reviewing the survey data, it may be revealing to analyze who agreed with the statement, "offender issues must be addressed first," since this is one of the main tenets of the "owning up" school of therapy.

In the case of juveniles, there were three respondents (17%) who said yes. Of these, one therapist not only said yes to "offender issues first," but picked all the answers, including "offender issues first," "abuse issues first," "simultaneous," and "flexible." Apparently, he thought all issues were important. The second therapist who checked "offender issues first" worked for a state-run youth and family treatment unit (mentioned earlier). His program was based on the owning up philosophy, and thus it is logical that he would agree with this statement.

The third respondent who chose "offender issues first" described herself as a "feminist" counselor. There is a feeling among some feminists that juvenile sex offenders are let off too easy, while their young female victims are exploited. This issue was discussed in Child Sexual Abuse: A Feminist Reader, by Driver and Droisen (1989). While this may be a valid point in some respects, it can be argued that juvenile sex offenders are already treated too harshly. After all, many juvenile sex offenders are themselves victims of sexual abuse. As this study proposes, a sympathetic approach may rehabilitate more young male sex offenders, thus reducing the number who go on to become adult sex offenders. The aim of this study is not to protect youthful sex offenders from punishment, but rather to help them heal their wounds and make a commitment to recovery. Any method that helps in this regard should be welcomed by feminist therapists.

In the case of adult sex offenders, five respondents (28%) agreed with the statement, "offender issues should be dealt with first." Of the five, two checked all the answers, "offender issues first," "abuse issues first," "simultaneous," and "flexible." Two others indicated that they work within the correctional framework described above, and the fifth was the feminist counselor mentioned above.

If these findings could be generalized, it would seem that support for the anti-sympathetic, "offender issues first" philosophy has its strongest support among correctional-based therapists and feminists. This would be an important finding, since professionals in the corrections field give the impression that "offender issues first" is the only acceptable approach. Obviously, not all therapists believe this.

A byproduct of the owning up model is behavioral therapists' promotion of aversion therapy assessment as the ultimate cure, even for juveniles. In fact, there is a growing movement to bring more aversion therapy into juvenile treatment. Not all therapists support aversion therapy, as the data in this study shows. In fact, supporters may be only a small proportion of therapists in the overall field of psychology.

Some therapists might consider it a mistake to introduce aversion therapy for general use with juveniles, since it is painful and embarrassing. It could be argued that the procedure itself would add to the abuse the juvenile has already suffered. Adolescents are in a transitional period, where their attitudes about sexuality are being formed. The penile plethysmograph apparatus, coupled with vile slide shows and audio suggestions--not to mention sniffing ammonia fumes or receiving mild electric shocks--could easily destroy the adolescent's ability to form normal attitudes about his own sexuality.

Who Supports Aversion Therapy?

Ten respondents (67%) said they approved of aversion therapy for adults (see Figure 5). This is more than half, but does not constitute a substantial majority. The respondents who chose this answer were spread across the spectrum of education levels, types of clients, and private or agency employment. Thus, if these results could be generalized, it appears that a majority of practitioners in the field of psychology approve of aversion therapy for adults.

Of the ten, six also approved of aversion therapy for juveniles. However, three qualified their answers with write-in comments: "Depends on situation," "Only if client meets strict criticism," and, "Case by case basis." Only three respondents made no comment when they said they approve of aversion therapy for juveniles.

Surprisingly, seven of these 10 respondents said they thought art therapy could be useful in treating juvenile and adult sex offenders. This seems to indicate that the two schools can work together and share ideas for sex offender treatment.

Conclusions

The results of this survey were more supportive than expected. Overall, many therapists approved of the four-phase treatment design, art therapy, and sympathetic, flexible treatment. Since the results tend to support the hypothesis of the four-phase treatment design, it is clear that the design merits further study. Perhaps it could be tested again, under the ideal conditions discussed earlier.

If it can be shown that sympathetic therapy reduces recidivism, this would build a case against plethysmograph assessment and other intensive therapies for juveniles.

This study was significant, in that it challenges the status quo of sex offender treatment. If the sample of therapists who took part in this study represent the general population of therapists, then there is more support for sympathetic offender treatment than those in the correctional field assume. It would be interesting to share this data with anti-sympathetic therapists who feel confrontational therapy, "offender issues first," and so on, are the only way to deal with juvenile sex offenders.

In the beginning of this paper, it was suggested that sexual abuse is an emerging problem in our society. Survey results show that 89% of the respondents believe we are only seeing the "tip of the sexual abuse iceberg" (Figure 2). This raises the question of whether society could be overreacting to juvenile sexual aggression; overreacting to the sexual abuse iceberg. In fundamental terms, this paper asks whether it is fair to confront and punish a 13-year-old boy who became a sex offender as a result of years of sexual abuse during his childhood. Wouldn't it be better to help him understand and heal the abuse? Perhaps further study on the treatment of juvenile sex offenders could help bring public opinion back to more liberal correctional methods.

True, juvenile sex offenders may need to be locked up, especially if they are violent or predatory. But they need not be "shamed" into a cure. The four-phase treatment design begins with the preliminary work of building openness, trust, and safety. This may be a good place to start in treating any juvenile offender, who is a victim of childhood sexual abuse.

References

Abbey, J.M. (1987). Adolescent perpetrator treatment programs: Assessment issues. ERIC document #ED285057.

American Psychiatric Association. (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 3rd ed., rev. Washington, DC: Author.

Axline, V.M. (1947). Play therapy. New York: Ballantine Books.

Axline, V.M. (1964). Dibs: In search of self. New York: Ballantine Books.

Blake-White, J. & Kline, C.M. (1985). Treating the dissociative process in adult victims of childhood incest. Social Casework, 66, 394-402.

Borzecki, M. & Wormith, J.S. (1987). A survey of treatment programmes for sex offenders in North America. Canadian Psychology, 28, 30-44.

Buck, J.N. & Hammer, E.F., Eds. (1969). Advances in the House-Tree-Person technique: Variations and applications. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Burgess, A.W., Hartman, C.R., McCormack, A., & Grant, C.A. (1988). Child victim to juvenile victimizer: Treatment implications. International Journal of Family Psychiatry, 9, 403-416.

Burns, D.D. (1980). Feeling good: The new mood therapy. New York: William Morrow and Co.

Calof, D. (1988a). Adult children of incest and child abuse, part one: The family inside the adult child. Family Therapy Today, 3:9, 1-5.

Calof, D. (1988b). Adult children of incest and child abuse, part two: Assessment and treatment. Family Therapy Today, 3:10, 1-7.

Carozza, P.M. & Heirsteiner, C.L. (1982). Young female incest victims in treatment: Stages of growth seen with a group art therapy model. Clinical Social Work Journal, 10, 165-175.

Carr, A. (1977). Final report on analysis of child maltreatment--juvenile misconduct association in eight New York counties. Washington, DC: National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect, Office of Human Development Services, Department of Health, Education and Welfare.

Chesney-Lind, M. (1988). Girls in jail. Crime & Delinquency, 34, 150-164.

Cohen, F.W. & Phelps, R.E. (1985). Incest markers in children's artwork. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 12, 265-283.

Cooney, J. (1987). Coping with Sexual Abuse. New York: Rosen Publishing Group.

Crain, W.C. (1985). Theories of development: Concepts and applications. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, Inc.

Daugherty, L.B. (1984). Why me? Help for victims of child sexual abuse (even if they are adults now). Racine, WI: Mother Courage Press.

Davis, L. (1990). The courage to heal workbook: For women and men survivors of child sexual abuse. New York: Harper & Row.

Dembo, R.M., Williams, L., La Voie, L., Berry, E., Getreu, A., Wish, E.D., Schmeidler, J., & Washburn, M. (1989). Physical abuse, sexual victimization, and illicit drug use: Replication of a structural analysis among a new sample of high-risk youths. Violence and Victims, 4, 121-138.

Denny, J.M. (1975). Techniques for individual and group art therapy. In E. Ulman & P. Dachinger (Eds.), Art therapy: In theory and practice (pp. 132-149). New York: Schocken Books.

DeZolt, E.M. & Kratcoski, P.C. (1989). Treatment of the sex offender. In P.C. Kratcoski (Ed.), Correctional counseling and treatment, 2nd ed. (pp. 348-363). Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.

Driver, E. & Droisen, A. (Eds.) (1989). Child sexual abuse: A feminist reader. Washington Square, NY: New York University Press.

Emunah, R. (1990). Expression and expansion in adolescence: The significance of creative arts therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 17, 101-107.

Engel, B. (1989). The right to innocence: Healing the trauma of childhood sexual abuse. New York: Ivy Books.

Estelle, C.J. (1990). Contrasting creativity and alienation in adolescent experience. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 17, 109-115.

Forward, S. & Buck, C. (1978). Betrayal of innocence: Incest and its devastation. New York: Penguin Books.

French, D.D. (1988). Distortion and lying as defense processes in the adolescent child molester. Journal of Offender Counseling, Services & Rehabilitation, 13, 27-38.

Gay, L.R. (1987). Educational research: Competencies for analysis and application, 3rd ed. Columbus, OH: Merrill Publishing Co.

Giarretto, H. (1982). A comprehensive child sexual abuse program. Child Abuse and Neglect, 6, 263-278.

Gil, E. (1983). Outgrowing the pain. Walnut Creek, CA: Launch Press.

Hains, A.A., Herrman, L.P., Baker, K.L., & Graber, S. (1986). The development of a psycho-educational group program for adolescent sex offenders. Journal of Offender Counseling, Services & Rehabilitation, 11, 63-76.

Hendricks, G. & Wills, R. (1975). The centering book: Awareness activities for children, parents, and teachers. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Jacobson, L. (1989). Visualization exercises for "Spirit in Art" and "Drawing From Your Dreams." University of California, Los Angeles: Unpublished.

Johnson, D.R. (1990). Introduction to the special issue on the creative arts therapies with adolescents. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 17, 97-99.

Kratcoski, P.C. (1989). Group counseling in corrections. In P.C. Kratcoski (Ed.), Correctional counseling and treatment, 2nd ed. (pp. 269-276). Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.

Landgarten H.B. (1987). Family art psychotherapy: A clinical guide and casebook. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Lew, M. (1988). Victims no longer: Men recovering from incest and other sexual child abuse. New York: Harper & Row.

Liebmann, M. (1986). Art therapy for groups: A handbook of themes, games, and exercises. London: Croom Helm.

Lombardo, R. & DiGiorgio-Miller, J. (1988). Concepts and techniques in working with juvenile sex offenders. Journal of Offender Counseling, Services & Rehabilitation, 13, 39-53.

Margolin, L. (1983). A treatment model for the adolescent sex offender. Journal of Offender Counseling, Services & Rehabilitation, 8, 1-12.

McGoldrick, M. & Gerson, R. (1985). Genograms in family assessment. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Naitove, C.E. (1982). Art therapy with sexually abused children. In S.M. Sgroi (Ed.), Handbook of clinical intervention in child sexual abuse (pp. 269-398). Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

O'Hare, J. & Taylor, K. (1983). The reality of incest. Women and Therapy, 2, 215-229.

Oaklander, V. (1978). Windows to our children: A gestalt therapy approach to children and adolescents. Moab, UT: Real People Press.

Piaget, J. (1959). The language and thought of the child, 3rd ed. New York: The Humanities Press, Inc.

Powell, L. & Faherty, S.L. (1990). Treating sexually abused latency age girls: A 20-session treatment plan utilizing group process and the creative arts therapies. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 17, 35-47.

Rhyne, J. (1984). The gestalt art experience: Creative process and expressive therapy. Chicago: Magnolia Street Publishers.

Rubin, J.A. (1986). From psychopathology to psychotherapy through art expression: A focus on Hans Prinzhorn and others. Art Therapy, 3, 27-33.

Rubin, J.A. (1987). Approaches to art therapy: Theory and technique. New York: Brunner/Mazel, Inc.

Shelden, R.G., Horvath, J.A., & Tracy, S. (1989). Do status offenders get worse? Some clarifications on the question of escalation. Crime & Delinquency, 35, 202-216.

Silver, R. (1988). Screening children and adolescents for depression through Draw-A-Story. American Journal of Art Therapy, 26, 119-124.

Stevenson, H.C., Castillo, E. & Sefarbi, R. (1989). Treatment of denial in adolescent sex offenders and their families. Journal of Offender Counseling, Services & Rehabilitation, 14, 37-51.

Straus, M.B. (1988). Abuse and victimization across the life span. Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins University Press.

Trotzer, J.P. (1989). The process of group counseling. In P.C. Kratcoski (Ed.), Correctional counseling and treatment, 2nd ed. (pp. 277-303). Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.

Van Ornum, W. & Mordock, J.B. (1988). Crisis counseling with children and adolescents: A guide for non-professional counselors. New York: Continuum.

Wadeson, H. (1980). Art psychotherapy. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Wenet, G. (1984). Risk scale. In F.A. Knopp, A survey of adolescent sex offenders in New York state. Syracuse: Safer Society Press.

Winton, M.A. (1987). Style analysis of sexually abused children in treatment. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 13, 67-70.

Wohl, A. & Kaufman, B. (1985). Silent screams and hidden cries: An interpretation of artwork by children from violent homes. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Wolf, R. (1975). Art psychotherapy with acting-out adolescents: An innovative approach for special education. Art Psychotherapy, 2, 255-266.

Other Resources

This list serves as a reference to other sources that contributed to the development and testing of the programmatic design.

Lectures and College Workshops:

Browers, R. (1990). So You Want to Help Someone. Marylhurst College, Sept. 15. Rebecca Browers provided an overview to the helping professions.

Calof, D. (1991). Treatment of Adult Survivors of Incest and Child Abuse. Marylhurst College, Jan. 11-12. David Calof explained the role of sexual abuse in Multiple Personality Disorder (MPD).

Carr, S. (1991). Sexual Abuse and Recovery: Treatment Issues. Oregon State Hospital, Feb. 27. A presentation by the Oregon State Department of Human Resources for state employees.

Funk, A. (1990). Introduction to Dream Work. Marylhurst College, Sept. 28-29. Annemarie Funk, M.A. provided an introduction to Jungian concepts of dream work, including symbols and archetypes.

Hindman, J. (1991). Trauma Assessment and Treatment of Sexual Victimization. Feb. 15. Jan Hindman, M.A., presented results of her research on sexual abuse trauma.

Leonard, K. (1991). Introduction to Family Art Therapy. Marylhurst College, Feb. 8-9. Kate Leonard, Ph.D., ATR, lectured on family systems theory and taught art therapy techniques that can be used with families.

Lichtenthaler, E. (1990). Family Systems Approach to Sex Offender Treatment. Western Oregon State College, Oct. 24. Eric Lichtenthaler, treatment coordinator for the Morrison Center "Responsible Adolescent and Parent Program," spoke about out-patient sex offender treatment.

Rhyne, J. (1990). Form as Content: Understanding Personal Constructs in Visual Language. Marylhurst College, July 27-29. Janie Rhyne, Ph.D. ATR, spoke about using art in gestalt therapy.

Turner, C. (1990). Introduction to Art Therapy Workshop. Marylhurst College, July 13-14. Christine Turner, M.S. ATR, director of graduate studies in art therapy at Marylhurst College, discussed art therapy.

Agencies:

Charter Hospital of Thousand Oaks, 1218150 Via Merida, Thousand Oaks, CA 91361; tel.: (805) 495-3292. Residential chemical dependency program for adolescents.

Heart Center for Recovery and Healing, 145 Wilson St. S., Salem, OR 97302; tel.: (503) 585-0351. Contact: Mary Hammond-Newman, MA. A counseling center for sexual abuse and recovery.

Jasper Mountain, Jasper, OR; tel.: (503) 747-1235. Contact: Judy Littlebury. Residential treatment for sexually abused children.

Polk Adolescent Day Treatment Center, 2200 E. Ellendale, Dallas, OR 97338; tel: (503) 623-5588. DARTS certified day treatment for severely emotionally disturbed adolescents. Contact: Larry Tang, Executive Director.

Poyama Land, 460 Greenwood Rd., Independence, OR 97351; tel.: (503) 581-6945. DARTS certified day treatment for severely emotionally disturbed children. Contact: Scott Berglund, treatment coordinator.

Red Willow Adolescent Chemical Dependency Treatment, Inc., Gervais, OR 97026; tel.: (503) 792-3697. Residential chemical dependency program based on 12-step process.

Responsible Adolescent and Parent Program, Morrison Center, 5205 SE 86th, Portland, OR 97266; tel: (503) 775-2442. Out-patient treatment and aftercare for juvenile sex offenders and their families. Contact: Eric Lichtenthaler.

White Oaks Dedicated to Recovery, 3750 Lancaster Dr. NE, Salem, OR 97305; tel.: (503) 585-6254. Residential and out-patient chemical dependency treatment.

Woodview-Calabasas Hospital, 25100 Calabasas Rd., Calabasas, CA 91302; tel.: (800) 382-3469. Residential chemical dependency program for adolescents.

Appendix A

Axline's Eight Principles of Play Therapy

The following eight principles were enunciated by Virginia M. Axline in her classic text on play therapy (Axline, 1947, pp. 73-74; elaborated pp. 76-135). Although written 44 years ago, these principles remain the cornerstone in the field of play and art therapy today.

1. The therapist must develop a warm, friendly relationship with the child, in which good rapport is established as soon as possible.

2. The therapist accepts the child exactly as he is.

3. The therapist establishes a feeling of permissiveness in the relationship so that the child feels free to express his feelings completely.

4. The therapist is alert to recognize the feelings the child is expressing and reflects those feelings back to him in such a manner that he gains insight into his behavior.

5. The therapist maintains a deep respect for the child's ability to solve his own problems if given an opportunity to do so. The responsibility to make choices and to institute change is the child's.

6. The therapist does not attempt to direct the child's actions or conversation in any manner. The child leads the way; the therapist follows.

7. The therapist does not attempt to hurry the therapy along. It is a gradual process and is recognized as such by the therapist.

8. The therapist establishes only those limitations that are necessary to anchor the therapy to the world of reality and to make the child aware of his responsibility in the relationship.

Appendix B

Creative Activities

The first activity comes from Windows to Our Children (Oaklander, 1978); the rest are from Art Therapy for Groups: A Handbook of Themes, Games, and Exercises (Liebmann, 1986, pp. 142-153).

Story Telling With Picture Cards

Oaklander (1978) recommends using an ordinary deck of tarot cards to play story-telling games:

A deck of tarot cards is a very fertile identification device, and the Rider deck has the most detail. I have an inexpensive deck that I use with children of all ages. Young children can select a card that appeals to them and weave a fantasy story around it. With older children I usually ask them to choose two or three cards that have some kind of impact--good or bad--upon them and to identify with the illustrations selected." (p. 84)

Advertisements Draw/paint an advertisement for yourself. This can involve "selling oneself" and bring up negative feelings from lack of self-esteem; can also involve thinking about the people to be attracted by the advertisement. Variations: (a) After each person has finished, others add additional points. (b) Advertisement to sell you as a friend, worker, parent, etc. (c) Write or draw advertisements for others.

Childhood Memories Draw your first or early memory, any childhood memory, or a memory which made a deep impression. These themes often bring up hurts from childhood that people have been unaware of, and can be difficult to deal with. It is important to allow enough time for discussion of these. Variations: (a) a warm or happy childhood memory and an unhappy one. (b) A good memory and a bad one. (c) An embarrassing moment. (d) Yourself as a child. (e) Memories associated with strong feelings.

Conflicts Depict any kind of conflict. Or more specifically, conflicting parts of your personality. Variations: (a) Animated metaphor of parts of personality in a cartoon strip. (b) Depict any present conflict, and your parents sorting out their conflicts. (c) Draw or model two opposing aspects of your personality. Give them voices and make up a dialogue.

Emotions Paint different emotions and moods, using lines, shapes, or colors. The emotions can be selected by the group. Variations: (a) Select pairs of opposites, e.g. love/hate, anger/calm, and combine into one picture. (b) Quick abstract drawings in response to a spoken word, ie. love, hate, anger, peace, work, family, etc. (c) Start on even note, doodling with crayon, then express strong negative emotion (e.g. anger), then finish in opposite mood. (d) Paint as many emotions as you can think of. (e) Select one emotion for a theme painting, e.g. fear. (f) Make a mask to express a particular emotion. (g) Mark different emotions in a circle and put colors to them. Week by week take each one and do a separate picture. (h) Draw objects associated with pleasant or unpleasant feelings or memories. (i) Situations, involving other people, in which you have felt angry, anxious, and peaceful. (j) Paint a "crazy" picture (as if you were crazy). (k) Cut out magazine pictures for particular emotions, e.g. angry people, and imagine what they might be saying. (l) Use clay to express strong feelings and make an "angry object," using tools to cut, hammer, bash clay, etc.

Fears Paint your worst fear, or one fear, three fears, or five fears. Variations: (a) Imagine you are hiding--where and from what? (b) Threatening situations. (c) You are adrift in a boat--what would you do? (d) You are lost in a forest--what would you do? (e) You are locked in a prison--what do you do? (f) Imagine a door or a gate--what lies behind it?

Good and Bad Depict your good side and bad side; things you like and dislike about yourself; or things you would like to keep or change; or strengths and weaknesses. Variations: (a) Clay shapes of aspects liked and disliked. (b) Masks that represent ideal and unacceptable sides. (c) Ideal self and real self. (d) Look at negative and positive aspects in a painting and have a conversation with both parts. (e) Changes made and to be made. (f) Use paper bag for faces on both sides.

Institutions There are many themes which are concerned with reactions to arriving at, or being in, an institution, where a school, hospital, or prison (where as a client or a member or staff). They are best tailored to particular needs and institutions. The examples below can be used with clients or staff: (a) Experiences of first day or first impressions there. (b) Story of how you came to be there, or in trouble. Can be taken on many levels. (c) Main concerns, personal or institutional. (d) How you see yourself, and how others see you, and how you would like to be seen. (e) Your institution with yourself in it. (f) Fold paper in half. Draw your life inside on one half, outside on the other half, and compare. (g) A "rock-bottom" experience, and present situation. This focuses on feelings of powerlessness and loss of control. (h) Situations and feelings which lead up to a particular crises, e.g. drinking bout, criminal offence, overdose, etc. (i) Your goals in your particular institution. (j) When leaving: feelings about leaving and what your experience here has meant to you. (k) What your institution does for you; what it does not do for you. (l) Portrait (realistic or abstract) of leader, therapist, teacher; this brings out feelings toward her/him and towards institution. (m) Feelings about approaching festivals (which may reinforce feelings of isolation, frustration, etc.). (n) Comic strip of what you would do if you could leave the institution for a few days.

Introvert/Extrovert List or draw imagined qualities of a person of opposite temperament to yourself (ie. introverts list imagined qualities of extrovert), then paint as if you had one or more of these qualities.

Life Collage Pick out from magazines pictures that are relevant to your life (10 minutes), cut out words (five minutes), and put together in collage representing your life (30 minutes). Variations: (a) Cut out a headline relevant to you and your life. (b) Draw your concerns and arrange on paper to form "life-space" picture. (c) Pick out three to five pictures which make a statement about you, or show things you are willing to share.

Lifeline Draw your life as a line, journey, or road map. Put in images and events along the way, drawn and/or written. Variations: (a) Select one section of your line and draw an image. (b) Choose one part only to depict as a line, or a particular aspect, e.g. friends, work life, sexual life, etc. (c) Use sections labelled "past," "present," and "future." (d) Draw your life as a maze, if appropriate. (e) Use the whole piece of paper to depict your lifetime, or use a roll of paper. (f) Lifeline as a spiral, starting from birth. (g) Continue lifeline into future. (h) Illustrate your life story with images from magazines. (i) Draw map of important things, places, and people in your life. (j) Place special emphasis on where you are going. (k) Survey past art work from specific period. (l) Include barriers and detours, and role play passing these. (m) Story of how you came to particular situation, e.g. prison, hospital, in trouble, etc.

Losses Draw a picture or abstract symbol of someone or something which has gone. Variations: Feelings surrounding this event. This theme may be very cathartic and should be used with care, especially if people have suffered recent significant losses; but it may provide a valuable starting point for sharing important feelings.

Mask Diary Members of the group draw or paint a mask as they arrive at the group, and throughout the life of the group. Towards the end of the sessions, the masks are spread out and each person shares their journey through their masks. In an ongoing group, a good time to share the masks would be after five to eight weeks.

Past, Present, and Future This is another view of "lifeline," but in more distinct blocks. Draw images of your past, present, and hoped-for future. Variations: (a) Concentrate on future only. (b) Use images from magazine. (c) Your life at particular moments, e.g. 10 years ago, one year from now, etc., or at particular ages. (d) Past, present, and future self-images. Explore any conflicts of content. (e) Concentrate on particular aspects of future, e.g. what job you would like, what sort of house, etc. (f) Imagine yourself at a crossroads; what are your alternative directions? (g) Decisions made/to be made. (h) Changes and hopes for the New Year, etc. (i) Things that may difficult in the near future. (j) Scale of states from "ideal" to "rock-bottom." Mark where you are now and the steps needed to move upwards. Perhaps link with "lifelines" to see what patterns have influenced you. (k) Yourself at this moment in the context of past and future life. (l) Personal coat of arms with spaces for specific information, e.g. hope for next year. (m) Feelings of leaving one experience and going to another. (n) Ideal world. (o) Where I came from, where I am now, and where I am going. (p) Unfinished business. (q) Regrets, and how you would liked things to be. (r) Losses you have suffered in your life, and what you would like to find in the future (see also "losses"). (s) People important to you, or important in the past. (t) Before and after: draw yourself or your life and how you felt before and after a particular event, e.g. accident, becoming ill, moving, etc.

Personal Landscape Draw a landscape (town, sea, or countryside) and relate it to your personality. Variations: (a) Draw window of any size. Show view through window and what is in room. Realistic or abstract. (Results are sometimes looking out, sometimes looking in.) (b) Take imaginary pictures with a shoe box camera, focusing on what is significant in room. (c) Paint yourself in a landscape. (d) Paint an ideal or favorite place. (e) Paint a place you dislike.

Personal Progression Portray the people in your life that influence you, during the first week of therapy, a course, etc. Repeat three or four months later.

Present Mood Paint a picture of your mood or feelings at the moment. If appropriate, depict a metaphor, e.g. "I'm all at sea," "Everything's blank," etc. Variations: (a) Use marks, shapes, colors to represent physical and emotional feelings of the moment. (b) Use symbols to express current mood. (c) Use doodles. (d) Paint a picture to represent "I am," "I feel," "I have," "I do." (e) Paint a recent or recurring problem or feeling. (f) Paint a pleasant feeling and an unpleasant feeling. (g) Feelings of leaving one experience and going to another. (h) Use for physical pain, e.g. headache, backache, etc. (i) Do a drawing of how you feel now. Then exaggerate that feeling, or part of the drawing, into a series of further drawings.

Problems Portray any current problem, especially if it is persistent or recurrent. Then do another picture, or a collage of any benefits of having the problem.

Recent Events Think back over last week/night and represent something that made you happy, and then something upsetting. Variation: Depict events of last week in strip cartoon form.

Secrets and Privacy Depict, realistically or abstractly, three things: (i) to be shared by the group; (ii) perhaps to be shared; (iii) not to be shared. In the discussion, people may decide after all to share (ii) and (iii), but there should be no pressure to do so. Variations: (a) The private and the shared you. (b) The part you show the world, and the part you do not show. (c) Being alone; being with others.

Appendix C

Case Studies from the Four-Phase Treatment Groups

The subjects in the pilot group did not exhibit particular difficulty when asked to "draw something." However, some were unsure of how to express subjective feelings, i.e. "Draw how you feel about your family" or "Draw your anger." This could be due to their being in the concrete stage of cognitive development (Piaget, 1959), where they do not yet think in abstract terms. One way to overcome this barrier was to use language they could understand. Instead of giving directions like, "Draw abstract images of your family members," the researcher learned to say, "Draw each family member as a shape." After several sessions, subjects generally became more at ease with abstract and subjective images.

The following descriptions illustrate how several subjects progressed over a six month period.

Donny's Movement Through the Four-Phase Program

Donny was one of the most troubled subjects in the sample. The following account shows how Donny was able to express his inner turmoil and progress through several stages in the art therapy group.

Phase I, step 1: Therapist reviews Donny's file. Donny had a particularly poor prognosis, since his violent tendencies were thought to stem from an organic brain disorder. His mother reported a difficult pregnancy and labor, with possible hydrocephalus at the time of birth. Donny told one psychiatrist, "Some of my brain has been erased." The psychiatrist wrote the following in Donny's evaluation: "Seriously dangerous, refused to be controlled." A second examiner described Donny as, "A predatory sexual offender who is untreatable and who will need to be locked up for years to come."

Donny was incarcerated for attempted sodomy and first degree sexual abuse. His record said he was physically abused by his father at age four and later sexually abused by peers in another institution. (Donny remembered during the course of therapy that he was also sexually abused by a female baby-sitter.) Described as an "oppositional youngster" who "lied, stole, and made threats of violence against his family," Donny once ran away from home carrying a knapsack containing only kitchen knives and a blanket.

Donny's clinical diagnoses were: Axis I--dysthymia, identity disorder, intermittent explosive disorder, and organic personality disorder (provisional); Axis II--pervasive developmental disorder, non-specific.

Step 2: Building trust. In his first group (11/15/90), Donny drew a picture of a battleship floating in a bloody ocean, with clouds and thunder overhead (see Figure 8). In subsequent groups, he drew pictures of the "hells" he has been through, including a picture of the devil, laughing "ha ha ha ha ha ha," as he pushes Donny into hell (Figure 9). The subject often spoke of violent dreams in which he felt his head being cut off by a guillotine, or saw others' heads being cut off. He described dreams of demons prodding him with pitch forks and faceless men threatening him with knives. He said he often "wakes up in a sweat" after nightmares.

Donny had difficulty taking part in group activities. He usually started out with the others, but then refused to cooperate further, as he focused on his own drawings. Despite his inability to cooperate, the researcher tried to support Donny, praising whatever artwork he produced. Donny enjoyed sharing his work with the group and talking about it. Responding well to the positive feedback, he soon felt confident that his drawings would be appreciated by the researcher and other group members. He began to open up and share his feelings, albeit violent feelings ("When I get mad I'll punch a punching bag or punch someone's face--it doesn't make any difference to me, if I'm mad").

Step 3: Transitional stage--Donny takes an interest in his own progress. After six meetings, Donny discovered a jagged shattered-glass-like image (Figure 10) that seemed to express what he was feeling inside. Drawing the image over and over seemed to facilitate something Donny was working through, so the researcher encouraged him to turn in as many drawings as possible. During a two week break in the group meetings, Donny produced 16 variations of the image.

The process of repeatedly (and almost compulsively) drawing a particular image coincides with Montessori's theory of child development. Montessori observed that children seek out activities at different stages to accomplish developmental tasks (Crain, 1985). Thus, a child at a certain stage may sit and work quietly with a peg board for hours on end, without adult supervision. The external task provides a means of working through an internal problem. Commenting on the Montessori process, an observer noted, "When [the children] finished they were rested and joyful; they seemed to possess an inner peace. It seemed that children were achieving, through intense work, their true or normal state" (Crain, p. 55). Thus the name, "normalization." The same process seemed to be at work when Donny repeatedly drew the shattered glass image.

One day, after an anger-releasing activity, the group members spontaneously talked about violent images they had witnessed--stabbings, shootings, fights, car accidents, times they had fired a gun, and so on. Donny, while sharing a drawing, had a breakthrough about his sexual abuse. He told the group that after a baby-sitter sexually abused him, he began having sex on his own at age nine. He turned to the researcher and said, "Isn't that kind of young to have sex?" The researcher replied, "Yes, but maybe it's because you were sexualized too early--then you tried it for yourself." Donny said, "Yes, maybe that's why I wanted to have sex so young." Donny said he was relieved to have figured it out. He said, "I thought I was just oversexed, or something. But maybe I'm not."

At the next meeting (1/21/91), two months after his first battleship drawing, Donny spontaneously drew a second battleship (Figure 11). This time the clouds and lightening had cleared and a bright sun hung in the upper corner. There was no longer blood in the ocean. Other boys drew war scenes, being preoccupied with the five-day old war in the Persian Gulf, but Donny's battleship had a deeper significance. He was beginning to understand why he should work on his sex-related problems. During the session, Donny read 10 pages from a book the researcher was using, The Right to Innocence: Healing the Trauma of Childhood Sexual Abuse (Engel, 1989), and asked to borrow it. He returned it the following week, saying that he had read most of it.

Phase II, step 4: Donny begins to explore his sexual abuse. In a private session, Donny volunteered the following statement, "I've been thinking a lot about the baby-sitter who molested me. I am very angry at her." The researcher asked Donny to talk further about his experience. She also asked him to talk about the victim he molested and the other times he had been abused. Donny was candid and forthcoming, cooperating completely with the researcher. The disclosure was not mechanical or forced, but rather a self-searching revelation of what he had experienced.

In this session, Donny and the researcher did an interactive drawing, without talking, where they took turns working on the same piece of paper. Donny insisted that the researcher draw the shattered-glass images, using a ruler. The researcher was able to enter Donny's world of sharp, angular lines, so typical of sexually abused patients. Donny was pleased with the finished drawing and titled it, "Hell Number One."

After the drawing activity, the researcher confronted Donny about his violent tendencies, asking why he said he would hit someone who hadn't done anything to him. Donny repeated that hitting someone, even if they are innocent, didn't matter, if he needed to vent his anger. He further stated that he felt like other people were against him and his violence was a way of defending himself. The researcher wanted to continue working on Donny's violent tendencies, but he was transferred to another cottage. Donny continues to make progress and has not reoffended.

Joel's First Steps Toward Resolution

Fifteen-year-old Joel was convicted of first degree sodomy and made a ward of the court. His step-grandfather sexually abused him as a child, and the same adult also sexually abused Joel's mother when she was a child. Joel's mother said she had overcome the abuse by her faith in God. Joel was also physically abused by his father. Examiners stated that Joel had no psychopathology or disorders, and appeared to be of average intellect. They said he had a poor self-image and tended to minimize his deviant sexual behavior. Joel had been placed in several sex offender treatment programs in the juvenile facility, but had reportedly been unable to make progress.

In the first art therapy group, Joel drew a wand-shaped image three times (see Figure 12 for example), another example of a subject repeatedly drawing an image. In subsequent groups he drew Native American images--warriors, desert scenes, eagle feathers, and so on. Joel was proud of his drawings because he considered himself part Indian. He asked for a drawing pad so he could draw during the week and frequently asked the researcher to take his finished drawings to "show her class."

Joel's first breakthrough came during an anger-releasing activity. The researcher asked one person in the group to draw a target, then asked all the subjects to put their perpetrator--represented by a name, a shape, or a drawing of a person--on the target. Joel put a symbol of a hat for his grandfather and a liquor bottle for his father. The researcher then taped the target on the wall and passed around a box of plastic foam packing material. She asked the group members to express their anger toward their perpetrators, while throwing plastic chips at the target.

Joel became absorbed, saying things to his perpetrators like, "I'm angry at you," "I'm angry because you hurt me," "You were my father, why did you hurt me?" "Why didn't you love me?" Joel progressed from throwing chips to pressing chips into the target and concentrating on his words, as if speaking directly to the perpetrators.

After the chips were cleaned up, the researcher passed out blank sheets of paper and asked subjects to draw the perpetrator again. This time they were to scribble over the picture, expressing their anger aloud again.

In this exercise, Joel crossed out the symbol of his uncle, but could not express anger toward his father. "It's my father," Joel said. "I still love him." He became very sad looking at the symbol of his father, unable to resolve the love-hate conflict. Joel said it was the first time he had ever confronted this dilemma.

Several weeks later, Joel and the researcher had a one-to-one session. Joel explained that he was falling behind in his offender treatment and that he feared he would be locked up until he was 21. The researcher asked what he had done to get into trouble in the first place. Joel explained that he had sexually offended his niece. He said he felt bad about it and that soon he would want to apologize to her, but wasn't sure if it would help. He said he felt sorry that he would never be able to return to his home, since his victim was often around the house.

The researcher asked Joel why he couldn't make progress in his sex offender treatment. He said he didn't like the treatment because it was too hard to face certain things about himself. He said he disclosed his offenses, but didn't know what to say beyond the disclosure. He admitted that his disclosures weren't very sincere, but he didn't know what more was expected. The researcher asked Joel if he felt he had made progress during the session and he said he felt different, cleansed, and that he wanted to change. He appeared remorseful and thoughtful, but depressed.

In a subsequent group meeting, Joel recounted the events that led to his arrest--being beaten by his father for his offenses, and so on. When he began to describe his father's reaction, he broke into tears. Later, he said he doesn't normally like to talk about his feelings, but this was an exception. He admitted that he still had a problem resolving his relationship with his father. Joel continues in the pilot group.

Other Results

In some cases, various creative activities helped the subjects understand themselves better. In other cases, creative activities helped the researcher better understand the subjects. Following are some examples.

Spontaneous drawings. Like Donny's first drawing--a stormy battleship scene--first drawings can tell a lot about a particular subject. In his first group, Craig drew a bear with a long nose resembling a penis (Figure 13). A drawing like this alerts to therapist to the trauma surrounding the client's sexual abuse. In fact, records reveal that Craig was sodomized by an older step-brother for two years, beginning when he was eight years old. Although Craig received treatment for the abuse, he went on to molest several younger children when he reached puberty. Craig continues to suffer enuresis and encopresis, which a doctor diagnosed as psychological--a traumatic reaction to the prolonged sodomy he suffered.

In a one-to-one meeting with Craig, he became aware that is resentful of his step-brother. Although the step-brother severely abused Craig, he didn't have to be locked up. But Craig was serving time for what he had done. Craig hasn't resolved these issues, but he has become aware of his feelings.

Family genogram. In his first group Billy appeared disoriented and depressed, and seemed to have trouble understanding his environment. According to his records, an MMPI evaluation revealed a tendency toward paranoid schizophrenia, but the examining physician hesitated to give this diagnosis. Billy had a slight speech impediment and spoke in a quiet tone. He gave the following information about his family for a genogram:

Billy: Okay, there's my mother. She has a little baby now, that's less than one year old. I had three little sisters, but two have been adopted, so they are gone. The other one is in a foster home.

Researcher: And your father?

Billy: My father got in a car accident when I was eight. He got wrecked up and had to be in the hospital a long time. Now he lives somewhere else.

Researcher: What happened?

Billy: He got brain damage and cuts on his arm. People said the accident was because of alcohol, but I don't think it was.

He continued talking about the accident, the car, and how much he missed his father. Apparently, the accident led to the breakup of the family. All the children had to go to foster homes, since Billy's mother was young and unable to handle the responsibility. Billy had lived in foster homes and juvenile facilities since the accident.

Billy's story alerted the researcher to the nature (and possibly the origin) of the boy's disorders. Billy, who also had to leave the group, did not have a breakthrough in understanding his feelings toward his father's accident. However, with more work in this area, Billy could have come to a deeper understanding of himself by such a breakthrough. Billy did, however, begin to think about the harm he had caused to others (described earlier).

Subjects' drawings [Editor's Note: six pages of artwork - sorry this is not included here.]

Figure 8. Donny's battleship, a destructive image.

Figure 9. The devil pushing Donny into hell.

Figure 10. An image Donny drew dozens of times.

Figure 11. Donny's second battleship: calm waters and sunshine.

Figure 12. Joel drew this image three times one day.

Figure 13. Craig's bear indicates possible sexual trauma.

Appendix D

Survey Packet

The following materials were sent to 50 experts in the field of sexual abuse and sex offender treatment. The packet included a letter of introduction, a diagram and explanation of the four-phase treatment design, and a two-page questionnaire.

Cover Letter:

March 18, 1991

Dear Sexual Abuse Counselor,

I am writing to ask your opinions about sexual abuse and sex offender treatment. There are also some questions about the enclosed four-phase treatment plan. Your input will be valuable, even if you do not treat juvenile sex offenders (i.e., you only work with child or adult victims of sexual abuse). However, if you no longer deal with sexual abuse, or do not wish to participate, please disregard this questionnaire. If there are several counselors in your office who would be willing to respond, please feel free to photocopy the questionnaire. I have enclosed a self-addressed, stamped envelope for your convenience, and ask that you return the survey before April 26. The questions shouldn't take more than 10 minutes of your time.

While this information will be used in the "Evaluation" section of a master's thesis, strict confidentiality will be preserved. If you want to know more about this study, or want to obtain a copy of any part of it, please contact me or make a note on the questionnaire. If you have any other questions or wish to talk to me, I can usually be reached at the phone number above.

Sincerely,

Nori J. Muster

Western Oregon State College

Enclosure

[Editor's Note: The graphs on these thesis web pages were lifted from old Pagemaker files, therefore the quality of the type is not perfect.]

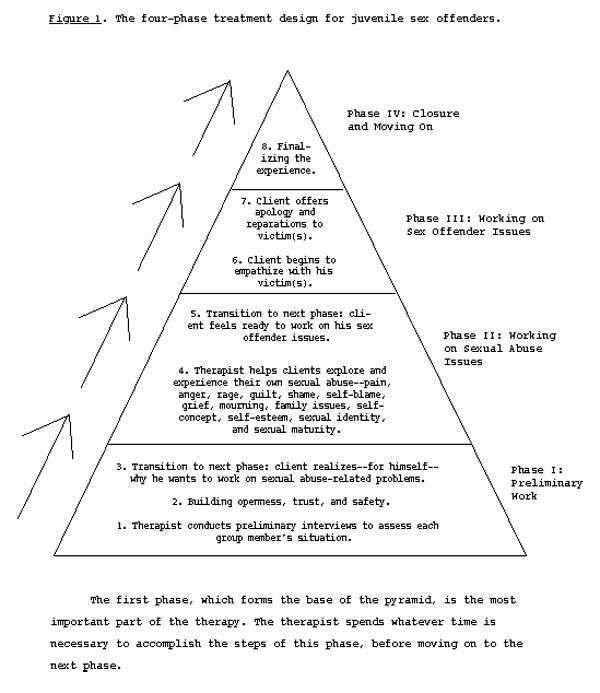

This design was tested in conjunction with a sex offender treatment program at an Oregon state training school. Subjects involved in the study were 13- to 17-year-old boys, convicted of first degree sexual abuse, rape, or sodomy. In addition to taking part in the four-phase treatment plan, the subjects lived in a residential milieu for sex offenders, worked in a treatment manual on a regular basis, and took part in sex offender counseling provided by the institution.

The treatment plan is a group therapy plan using art therapy activities. There are two pivotal points in therapy, called "breakthrough" points, where the client and therapist notice a genuine change in the client's behavior and attitudes. These are, "Step 3: Client realizes--for himself--why he wants to work on sexual abuse-related problems," and "Step 5: Client feels ready to work on his sex offender issues." The apex of the program is, "Step 7: Client offers apology and reparations to victim(s)," which comes at the end of Phase III. The act of apologizing to the victim confirms the sex offender's understanding that his acts were wrong, and that he has learned from his mistakes. The final phase, Phase IV, gives closure and wholeness to the client's therapeutic experience.

Note to professionals: This description, extracted from a six page "Procedures" section of a graduate thesis, is admittedly brief. If you need more information to complete the questionnaire, contact Nori Muster [updated contact information - click here].

Sexual Abuse Treatment Questionnaire

Professional Information:

I am an:

____ M.D. ____ M.S.W.

____ Ph.D. ____ Licensed counselor

____ M.A. or M.S. ____ Other: __________________________

I work in:

_____ a private agency ____ private practice

_____ a public agency ____ I take court referrals

I work with:

____ child sexual abuse victims ____ juvenile sex offenders

____ adults molested as children ____ adult sex offenders

Sex Offender/Sexual Abuse Issues:

I believe ______% of sex offenders were sexually abused as children.

In my experience, ______% of sexually abused children act out sexually.

I believe that, if left untreated, ______% of sexual abuse victims will eventually offend sexually; ______% will develop other aggressive behaviors.

There are a great many people who block out memories of sexual abuse. Therefore, we see only the tip of the sexual abuse "iceberg." ____ Agree; ____ Disagree.

____ I have heard of using art therapy with sexual abuse victims.

____ I have heard of using art therapy with juvenile sex offenders (besides this study).

In your work with sexual abuse victims (any age; check all answers that apply):

____ I prefer permissive, non-directive therapy.

____ I prefer confrontational therapy.

____ I believe sexual abuse is an all-family problem.

____ I take a victim's advocate stance.

____ I prefer cognitive/behavioral therapy.

____ I prefer (other theoretical framework): ______________________________

____ I use art therapy in my work with sexual abuse victims.

____ I treat sexual abuse victims in group therapy.

____ I recommend books like The Courage to Heal Workbook, by L. Davis, or Victims No Longer, by M. Lew, to my clients.

When treating adult incest victims, my policy toward the family is (check all that apply):

____ I try to involve family members in therapy, if they agree.

____ I discourage any contact with the family during therapy.

____ I work toward the client's eventual confrontation with the family.

____ I work toward the client's eventual reconciliation with the family.

____ Generally, I do not believe reconciliation is possible.

____ If the incest victim is a child, I require family participation.

____ If the incest victim is a child, I require separation from the offender.

____ Other: _______________________________________

In my opinion, when treating juvenile sex offenders, who were sexually abused as children (check all that apply):

____ Offender issues should be dealt with first.

____ Sexual abuse issues should be dealt with first.

____ Abuse and offender issues should be dealt with simultaneously.

____ The therapist should be flexible about what to work on first.

____ Since offenders are criminals, only the criminal behavior need be addressed.

____ Art therapy could be useful in juvenile sex offender treatment.

____ I would use sympathetic methods that are normally used with sexual abuse victims.

____ Sympathetic forms of therapy tend to reinforce minimization and denial.

____ I approve of confrontational group therapy for juvenile sex offenders.

____ I approve of aversion therapy, including penile plethysmograph assessment.

____ I approve of drug, psychosurgery, or physiological castration.

In my opinion, when treating adult sex offenders, who were sexually abused as children (check all that apply):

____ Offender issues should be dealt with first.

____ Sexual abuse issues should be dealt with first.

____ Abuse and offender issues should be dealt with simultaneously.

____ The therapist should be flexible about what to work on first.

____ Since offenders are criminals, only the criminal behavior need be addressed.

____ Art therapy could be useful in adult sex offender treatment.

____ I would use sympathetic methods that are normally used with sexual abuse victims.

____ Sympathetic forms of therapy tend to reinforce minimization and denial.

____ I approve of confrontational group therapy for adult sex offenders.

____ I approve of aversion therapy, including penile plethysmograph assessment.

____ I approve of drug, psychosurgery, or physiological castration.

In my opinion, when treating sexually abused children who act out sexually (check all that apply):

____ Offender issues should be dealt with first.

____ Sexual abuse issues should be dealt with first.

____ Abuse and offender issues should be dealt with simultaneously.

____ The therapist should be flexible about what to work on first.

____ Since offenders are criminals, only the criminal behavior need be addressed.

____ Art therapy could be useful for children who act out sexually.

____ I would use sympathetic methods that are normally used with sexual abuse victims.

____ Sympathetic forms of therapy tend to reinforce minimization and denial.

____ I approve of confrontational group therapy for children.

At what age should a sexually abused child be held responsible for aggressive sexual behavior? _____ Why?

(optional; use other side if necessary)

The Four-Phase Treatment Plan for Juvenile Sex Offenders

After examining the enclosed materials, please answer the following questions (check all that apply):

____ The four-phase treatment plan appears suitable for juvenile sex offenders, if used in conjunction with the therapeutic milieu described.

____ The treatment plan would be useful in other situations, as well.

____ The treatment plan is too lenient, too sympathetic to have any effect.

____ I'm not against leniency, but I would make many changes in the treatment plan, as it is described herein.

____ Juvenile sex offenders would take advantage of a treatment plan like this to avoid responsibility for their sex crimes.

____ The treatment plan might be good for addressing offenders' sexual abuse issues, but not until they have completed regular sex offender treatment.

____ The design looks okay; it's very similar to what I already use, or would use, with juvenile sex offenders.

____ I believe this treatment plan would have as much chance of working as any other treatment plan.

____ Are you aware of any researchers who promote a similar treatment plan? Who?

____ Any other comments? (optional; please use other side)

Thank you for your cooperation. If you wish to receive information about the results of this survey, please indicate your name and address here:

Extra survey questions--

As a [juvenile training school] employee, working in [the ward where the pilot study took place], you have been in direct contact with the subjects who participated in this study. Therefore, you may have valuable insights on the program that no one else can give. Please answer the the open-ended questions on on this sheet and enclose it when you mail in the longer survey. I realize each question demands a 10-page answer, but just write the first few things that come to your mind. Thank you, and again, your feedback is appreciated.

1. How well do you feel these groups fit into the established structure of the Kappa sex offender treatment program?

2. In your view, how did the individual students react to the groups?

3. How helpful do you feel these groups have been in motivating the students to work on their sexual abuse issues?

4. How helpful do you feel these groups have been in motivating the students to work on their sex offender issues?

5. In your estimation, did the groups have a positive effect on the students who took part? If so, can you mention any specific results?

6. Do you feel these groups have been worthwhile for the students who took part?

7. Any other observations, comments, questions--

Graduate students are welcome to replicate my study, but if you use my materials or quote from my thesis, I ask that you acknowledge my contribution to your work. Please cite me as follows in your references: "Nori Muster, author of A Four-Phase Treatment Design for Juvenile Sex Offenders, Western Oregon University, 1991."

more graduate work

Index