This part of the interview is about my stepfather's years at Capitol Records, and then a brief section at the end about his career before and after Capitol. He is currently a working musician in Tempe, Arizona.

Don Hassler History

Nori: What years did you work for Capitol and how did you come to work there?

Don: I started with Capitol in 1953 working as a salesman out of the branch in Illinois. I was transferred to the Capitol headquarters in Hollywood, California, in the spring of 1955, in about April or May. I continued to work in the Hollywood headquarters until 1961, when I left to work for another company in Santa Monica. When I started I was a salesman covering the downstate [Illinois] Capitol records dealers. Downstate included Danville, Kankakee, Champaign-Urbana, Peoria, Canton, LaSalle, Peru, and small towns all around there south and southwest of Cook County.

Nori: What kind of music were you selling?

Don: Everything - classics, pops, singles, and albums - 45 RPMs had just come out then. So jukeboxes were not only using 78 RPMs, which were singles, but starting to switch over to 45s, which were smaller, more compact, and actually had a little better sound quality. The record stores I sold to still sold a lot of hit singles for 89 cents. You could get a hit single like "Vaya Con Dios" by Les Paul and Mary Ford, or "Young at Heart" by Frank Sinatra, or "Wheel of Fortune" by Kay Starr. People would buy those to play on their home record players. Also, jukebox operators would buy them to put on the jukebox in restaurants and bars, hotel lounges, and places like that, where people wanted to play music. In those days I think you could get for a quarter you could get a play of a record.

Paula: Tell her about the mafiosos in Southern Illinois!

Don: I had to call on the operators who had the jukeboxes in taverns and places like that. A lot of the jukebox routes were owned by mobsters.

Nori: Dad told me one time that anytime you have a machine that takes coins, the mob is behind it.

Don: He's right on. I remember walking into the big jukebox operator in Joliette, IL. It was an old warehouse in a kind of run down area. You could hardly even find the door to the place, it looked like the back door of Tony Soprano's office. You'd walk in there and there's this giant warehouse and four or five guys are standing there counting money. And all I had to do was walk in there and say, "I'm from Capitol Records and we've got this new Frank Sinatra record." And they'd say, "Aw, that's fine, we'll take 500." Just like that. These guys were up on stuff like that. There wasn't any selling to do, they either wanted it or they didn't. I'll tell you, I was scared to go in there. It was creepy. They put Frank Sinatra number one on every jukebox. [click here to see some of his album covers]

Nori: He was tied in with the mob too, wasn't he?

Don: Well, he had friends in the mob. I don't know if Frank was actually involved in any mob activity. Might have been when he was a kid, but he had a lot of friends who were Italians and they were in the mob. They were his friends.

Nori: He was Italian, right?

Don: Oh yeah, as Italian as Mussolini, or more.

Paula: Well, didn't they promote other Italian artists too, like Vic Damone? [click here to see one of his album covers]

Don: Yes, Johnny Desmond, Vic Damone, Tony Bennett, you name it.

Nori: The jukeboxes liked the Italian guys, they were Italian.

Don and Paula: Right.

Don: After I was selling for about a year, year in a half, I was promoted to promotion manager in the Chicago branch. My job then was working with Capitol Record artists; those who came to town for appearances on the stage or appearances in concert, or just traveling through to promote albums. My job was to get them connected to disk jockeys, primarily, so they could be interviewed on the radio or TV. There were a few programs on TV where they could be contacted, and where they could promote whatever album they had, or whatever single they had. I remember, for example, meeting the Four Freshmen for the first time at the University of Illinois in Champaign, when they were making their first stage appearances at the university. They had a huge following even then, 1954 we're talking about. They practically sold out the field house there at the university for their concert and it was a huge success, and of course those guys went on to make some great hit records for Capitol. I kept up with them all during their career. I used to play softball with them when I got to the Hollywood office. That was an example of what a promotion manager did. I also did that in Los Angeles for a while after I got transferred out there.

Nori: So did you know the DJs and say, "Guess what I have coming up now."

Don: I got to know the DJs. In return for making sure that they had the newest records promptly, if I could do my job that way, I'd bring the new releases around, they would set up appearances for the artists I was trying to expose. I would personally take the artists from station to station. They were radio stations in Hollywood for example, KMPC, KFWB, KLAC, KPFK. There were about six or eight - KBIG out of, well the transmitter was in Catalina, but the studio was in L.A. About six or eight of those stations had all the listeners. They were the disk jockeys - entertainment people. People listened to the disk jockeys in those days like people listen to talk radio today. It was all AM radio. Today there are hardly any disk jockeys left on AM radio. They're all talk shows, as in Rush Limbaugh and people like that.

Nori: What did you do when you moved to work at Capitol in Hollywood?

Don: When I first moved to Hollywood I was in charge of a group of albums called "Kenton Presents." Stan Kenton wanted to showcase some of his musicians that played in his band. These musicians had some standing on their own. They had reputations and were known individually because they were featured soloists. Stan wanted to make an album series of those guys and he was on the road all the time. He never had the time to do that himself. I got to know Stan in Chicago through a fellow named Al Latauska, who was a regional sales manger for Capitol then. Al recommended me to Stan and they transferred me to Hollywood to make the Kenton Presents series. I was involved in A&R in the recording activity for about a year and a half. Then for whatever reason they decided not to continue the Kenton Presents series and the job that I was doing was discontinued, so I went back into marketing. I worked on promotion at the branch level for a while, then went back into the tower in a marketing job which involved special markets. I was involved in selling phonographs and accessories, marketing foreign albums, and things like that. It was sort of a catch-all. If it didn't fit into classics or pops, or albums, or singles, they tossed it my way and I'd do it. [click here to see one of the Stan Kenton Presents album covers]

Nori: Would you explain exactly what an A&R person does?

Don: A&R is artist and recording. In a record company the A&R people are like the R&D people in a major corporation. They're the ones that are finding new artists, signing them up, and making albums by those artists. That's who a new group today, a young group that wants to make it with a record company, will do a few concerts and make a few appearances, and then make a demo CD and send it to the A&R people. A prime example of somebody like that is this guy Phil Spector, who did A&R. He was a really big record producer. Record producers work in the A&R departments of the record companies they work for. They take charge of the artists, they help develop their career, they are very influential in producing the records for those artists, and maybe even helping them set up concert tours and things like that. Some of them write arrangements. A guy like Quincy Jones, who is really big in production and even in movies now, well he played trumpet with Count Basie (or maybe it was piano) for a long time, but he became a record producer and he was a big time guy for a long time.

Disk Jockey Payola

Nori: Well, I don't have any idea about this, but over the years there's been controversies that the record companies would pressure D.J.s to play certain things or there was some kind of kick-back schemes. That might of started later, but did you have any experience of that?

Don: It started before that. There was an interesting relationship between record companies and D.J.s. The record companies wanted lots of air play and every company wanted their records to get first place and get the most air play, but disk jockeys wanted to get favorable treatment in terms of hot new releases that might become hits. So it was a quid pro quo if you will between the disk jockey and the promotion guy for the record company (which I was one of) to make sure that you treated all the disk jockeys as well as you could and give all of them as many opportunities as you could. And if you really wanted to have an album or a record promoted heavily, you'd call in a few favors, you know, make sure they got some things ahead of time. And some companies would actually pay the disk jockeys - they called it payola - to play their records more than somebody else's records. This happened all over the country and there was a big scandal, and finally some legal action against payola, which happened somewhere in the late 50s.

Nori: Now they just give them coke.

Don: Yeah, well whatever they give them. Cash or coke, or whatever you do.

Nori: Take them out to fancy places.

Don: Capitol Records, the major labels Capitol, RCA, Columbia, pretty much did not do anything in the way of payola. I never gave a dollar to any disk jockey, but I did try to get artists around disk jockeys that wanted them. I would take disk jockeys out for nice means and maybe occasionally get tickets for things, stuff like that, especially Capitol artists at concerts. But there were never any dollars changing hands. And there were times when we wanted that. We had a record by Kay Starr called "Wheel of Fortune," but the hit record was on another label and I wanted Kay Starr's record to be played more, and I just did whatever I could to get it played more. Maybe I would see the disk jockey more often than the other guy, or for some reason the disk jockey liked me better.

Nori: Do you think any of your competitors at the other record companies were doing payola?

Don: Not of the major companies, but some of the minor labels, which were distributed by independent distributors, and especially the minor labels, would just budget a certain amount of money as part of their advertising budgets and they would pay the disk jockeys to play their records., to try to get a good record blasted off as a hit. I can't think of whose record was opposing Kay Starr's, but that was one record that was promoted with a certain amount of payola. Patti Page had some records on Mercury and there was a lot of thought that Mercury Records was encouraging payola through their distributors. They had some pretty good artists. There were people like Aretha Franklin, who got her start on Mercury. And an instrumentalist named Mitch Miller who was an A&R guy, who made some pretty good hit records. Those were very likely started out in major markets by getting the disk jockeys to give them a little extra push.

End of the Capitol Days

Nori: By the time you and Dad left . . .

Don: It was slowing down, but all the hot guys had gone on to other things. Frank Sinatra had his own label called Reprise. Mike Maitland, who was the national sales manager, went to Warner Brothers. Your dad went elsewhere, I went elsewhere. Not that we were all the key players, but the whole management changed. Glenn Wallichs retired. Some of the artists went on to other labels. Even Stan Kenton, who was a mainstay of Capitol Records in the early years, went elsewhere. So, things changed, but it was a really great place to work because there was just always something happening. It was really neat. When I first came out to Hollywood, the Western region had its summer sales meeting at the old Coronado, down in San Diego. That was in about 1956 or 57, something like that. I'll never forget that meeting because here were all these guys, young vibrant, everybody just all fired up and ready to go. Of all places they could have chosen, that Coronado was a really great spot for a sales meeting. I'll never forget it. It was my introduction to the West Coast. The year before the sales meeting was in Lake Placid, New York, and the year before that it was in Estes Park, Colorado. So they were doing a lot of stuff in those days. One year when they were introducing the fall albums, there were some artists that were going to perform for the sales force, so they divided them up into three regions - the east, the west, and the south. The south region had all the country artists. We took a show on the road and we played at the Capitol branches in about four or five cities. I was one of the guys responsible for making the tour work. We had Tex Ritter (father of John Ritter), we had Faron Young, Hank Thompson was another one. We had a lot of people whose names you might not recognize, but they were really hot in the country [scene]. We just took a regular concert tour on the road and we flew all over the place. Capitol was backing it because at every stop, all the dealers in that general area were invited to come in and hear the Capitol artists and have a party and have dinner and hear what all the new albums were going to be. It was really cool. They had one in the east and one in the west, in addition. I did the one in the south.

Nori: What year was that?

Don: That was probably 1958. The actual years between 55 and 61 it's hard for me to pick which exact one it might have been.

Nori: Just one year?

Don: Tex Ritter drank so much in that one tour that I think they decided it was too expensive to do it again. Boy, was he a souse, whoo.

Don Hassler After Capitol

Nori: Okay, so you went from Capitol to Transis-tronics. What did Transis-tronics do?

Don: We made a little bitty transistorized amplifier and tuner. The very first one on the market. Transis-tronics was Transis (like transistor) and tronics (like electronics). Everything else was tubes until then. It was the first small, transistorized, all solid state, no tubes. The only problem was, only about half of them worked. We had a massive exchange program going all the time. The transistors burned out. They weren't designed well. The were germanium transistors and what they wanted and needed and eventually got was silicon transistors.

Nori: So the company had a good repair program?

Don: The repair program was "take it back and give them another one." Give them one that worked.

Nori: So they were real generous?

Don: Real generous. Our biggest account was Radio Shack.

Paula: They went broke.

Don: Well, a long time after that. Radio Shack kept it going for a long time. That was an opportunity for me to really get to know the national sales scene. When I went to Concord I was ready to go.

Nori: What did Concord sell?

Don: Tape recorders.

Nori: So the big, old reel to reel things?

Don: Reel to reel. Then we started to make cassette recorders just as I left there. The reel to reel small ones were little 3-1/2 inch jobs. We had the first voice-activated 3-1/2 inch recorders. You turn it on and push the voice activated button, then when you started talking it would start to record, then when you stopped it would stop. It's pretty handy.

Nori: How long were you with Concord and where did you go after that?

Don: I stayed at Concord till 65, which is about three and a half or four years. I worked for Mad Man Muntz, who invented car stereo, for about a year.

Nori: Didn't Muntz also sell TVs?

Don: Early on, in the late 40s and earlier in the 50s, he was a TV guy.

Nori: Putting a TV in everyone's house.

Don: Yeah, but car stereo was his thing. He had four-track Fidelipac, it was the precursor to eight-track tapes. He had an installation place in Van Nuys that was installing car stereos as fast as people would come in. Everyone who worked for him would drive a white Lincoln Continental with a stereo built into it. Including me, I had one. It was great.

Nori: It was a company car?

Don: Yeah, sort of. He paid for the cost of it. But working for Mad Man Muntz was no good. I joined a rep firm run by a guy named Mike Stobin. It was a firm just like, you remember Irv Stern, this was the kind of business Irv was in.

Nori: Wasn't Irv with Koss, or something?

Don: That was one of the companies he represented. They guy I went to work for represented a speaker line, a line of accessories, some other things. He needed an extra salesman and he made me a good deal with commissions and things like that. From then on I stayed home. I didn't travel anymore, except to Phoenix.

Nori: Then in 1970 you moved here [Arizona] and bought Hesslers and Audio Specialists [a retail home entertainment company].

Don (looking through files): That's the tuner we sold. It was pretty small, 3 inches high, 10-1/4 wide and 8-1/2 deep. The tuner was a separate piece. There's a picture of the amplifier somewhere in here. Bernie Cirlin actually issued stock in his company. People even bought it. This is the amp and this is the tuner, and you just stacked them on top of each other. We sold them for $150. Okay, let's see, here's more Capitol stuff. Oh, here's me appointing people. Capitol appointments.

Don Hassler, Pre-Capitol

Nori: What kind of education did you need, what did you have to do to prepare, where did you work before Capitol?

Don: I worked in a radio station in Chicago. I didn't really prepare to go to work at Capitol, except that I was pretty familiar with recording artists and music, and things like that because I'd been a musician for a long time. I was still playing in those days. When I worked at the radio station I was in the radio library. Radio stations in those days - and still - have pretty substantial record libraries. Some of them very big record collections. In those days they were all single records and a few albums. The record library was responsible for keeping track of everything they had and getting everything going when they needed to for the disk jockeys.

Nori: Like when someone made a request, you had to run back there and grab it for them.

Don: Well, the disk jockey would usually do that.

Nori: But you had to keep everything all organized.

Don: We kept it organized and we pulled records for programs because a lot of the disk jockeys then would decide what records they wanted to play ahead of time, and they'd write it all down on a piece of paper. We'd have all the records stacked up, ready for them to go. In Chicago, because of the union rules, the record itself had to be played by a member of the musician union. This was because James Petrillo, who was national president of the musicians union, was also head of the Chicago local. He had enormous clout in Chicago, so wherever he could get work for musicians, he would do it. So that was one of the jobs they had, spinning records in the radio stations. The disk jockey never touched a record. Now that's all changed, I mean it's not like that anymore. But in those days, there was the engineers in the control room. The disk jockey was sitting in the studio with a microphone, and over there on the side was a guy that spun the records who was a musician.

Nori: Just in Chicago, though?

Don: There may have been a few other cities that had it, but it was mostly in Chicago.

Paula: New York, too.

Nori: They have to hire an extra guy.

Don: I was a member of Local 10 when I lived up there. I belonged to that union. But I wasn't a record spinner. You didn't have to belong to the union to work in the library.

Nori: That was pretty close to your college, because you went to Northwestern, right?

Don: I went to work in the radio station in 1950, right when I graduated.

Nori: What were you doing during college?

Don: When I was in college I was mostly playing in bands. I always had a band job that worked enough weekends, or proms, or parties, or whatever, to keep me in spending money and to pay part of my tuition and part of my rent and stuff like that. Also I worked at the mess hall, the student lounge, I guess you would call it, a few hours a day for meals. I didn't have any expenses for meals except for burgers and beer elsewhere.

Nori: So your parents paid the rest?

Don: They paid the tuition and some of my room rent.

Nori: Were they okay with you being a music major?

Don: Yeah, they were pretty cool about that. Dad and Mother really encouraged me. Unusual because the whole family was a family of engineers and mathematicians, and in the case of my mother's dad, accountants. Music was not exactly a career that they might have thought of for me, but my mother backed me all the way and my father did too. My objective was not to be a performing musician anyway. I wanted to do other things in music, mostly arranging, maybe A&R work, which I did for a while at Capitol. It was far enough away from wanting to graduate from college and then go on the road with a band playing one-nighters. That was not my idea of what I wanted to do. Or even become a symphony musician.

Nori: It's hard to make much money as a musician.

Don: It's not only that, but you can't last very much longer than five or six or eight years doing that. It's really a tough life.

Nori: What about those musicians at Capitol. Did they make a pretty good living?

Don: The ones that became well known. There were two kinds of musicians there. One kind are the studio musicians who come in and back up the recordings. Those guys do very well. They live in Los Angeles and become what they call "first call" musicians. That means when the contractor needs somebody for a record date, they call them first. Most of them worked in the movie studios as well and they made very nice incomes for a three hour recording session. Those musicians did great. And the well known artists like San Kenton, Kay Starr, and Les Paul and Mary Ford, and people like that also did well because they were stars. The guys who backed up those people on the road didn't always have that great of a thing. When Stan Kenton's band came to L.A. and if they were going to record, it was great and the guys made extra money when they were recording, but they were slogging out one-nighters other than that. They were taking busses and trains from Fargo, ND to Mineapolis, or someplace like that, to play the next job. There aren't that many one-nighters around anymore. Most big artists have these huge concerts, then they break down and go to the next gig and that's about three days away, and then they have another huge concert, and so forth. The traveling bands in those days were playing in ballrooms for dancers and they might draw three or four hundred people, or maybe 800, or maybe 1,200, depending on how big the ballroom was. But there wasn't that much money around for 1,200 people, compared to a concert out there at Sun Devil Stadium where you get 40,000 people. So that's one of the ways performing music has changed.

Nori: Do you think the unions did very much to help musicians back then?

Don: I think the musicians union did as much as they could and one of the great breaks was what they called the "Music Performance Trust Fund." That's a fund set up by the union, it's an independent organization that collects a fee for every record and CD sold, and that money goes into trust and its used to promote live music in every city where there's a union local. Here in Phoenix, they do music in the parks, libraries, nursing homes, retirement facilities, places like that. Half of the cost of those are paid for out of that trust fund, so musicians can still get work even though people are playing records instead of hearing live performances sometimes.

Nori: Did the unions set a base pay scale, like if you play on this record you have to be paid x amount?

Don: That's right. There's a pay scale for the first three hours, then for each half hour of overtime. The pay scale in a place like Los Angeles is firm and that's a union town. Nobody works out there who's not a member of the union.

Looking through Files

Don (looking through old paper work): This is what we were selling when I worked at Concord. It looks like a TEAC, actually.

Don: Oh, look at this, oh my god. This is from my secretary at Capitol.

Nori (reading): "D: Like, thanks for being the greatest boss in the world! I hope my next three years are half as pleasant as the last three have been. The best to you in everything you do. You deserve it. S." Dated June 10, 1961. The card says, "I hate to see you go," then you open it up: "It's almost like losing a friend."

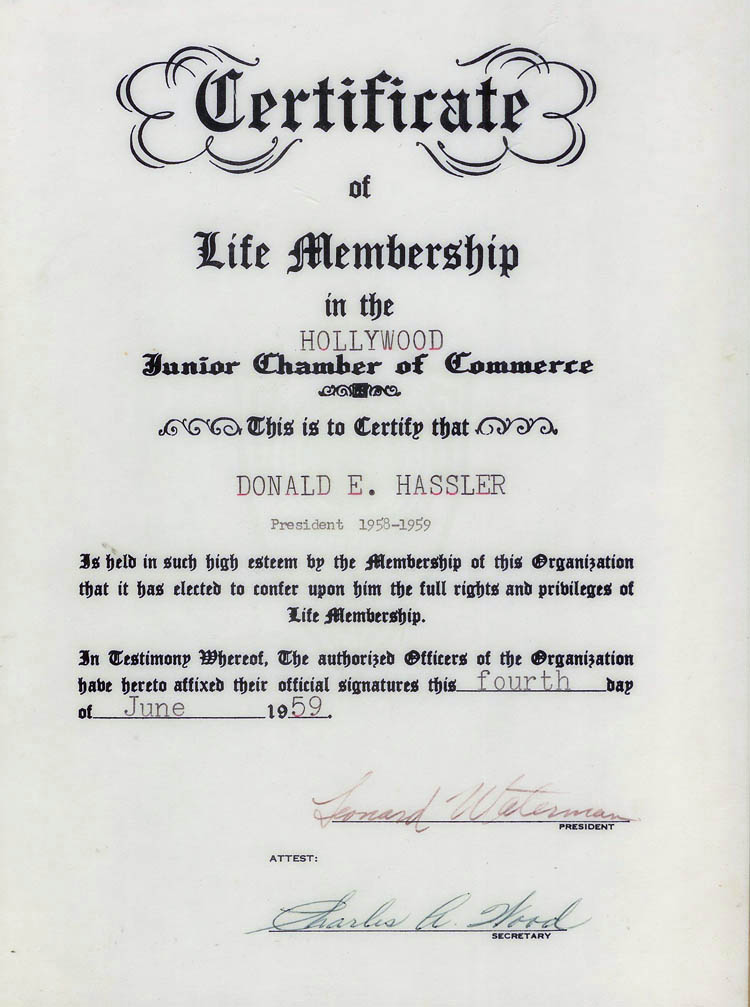

Don: This is one of the things I did when I was active in the community there. I was president of the Hollywood J.C.s. Here's a picture of us passing the gavel from one guy to the other. I'm not sure who got the gavel. This is the Citizen News, Jan. 9, 1959. That's me right there with the funny glasses.

Nori: It doesn't look like you.

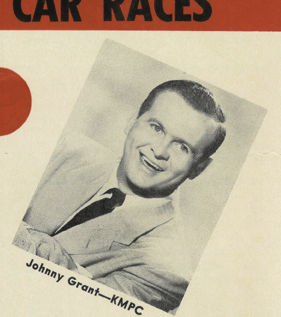

Don: I think I ditched the glasses after I got here I think I put the contacts in. Hodies [sp?], that was the name of the restaurant over there on Gower. Oh, my gosh, look at this. I haven't looked at these things. See this guy, right here, you recognize his name?

Nori: Johnny Grant, the mayor of Hollywood!

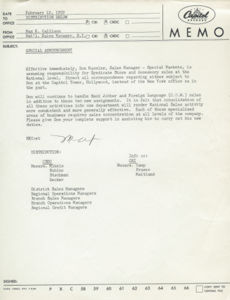

Don: That's him, only this is him in 1956. He's still doing it. He's 80 years old now. Johnny Grant's been active in that stuff. He was the main host at the tower opening. He was there with the spotlights and all that and watching it all happening, and welcoming people. Here's how they used to announce management changes. An internal memo.

Nori (reading memo): "Date: February 12, 1959; To: Distribution Below; From: Max K. Callison; Office: Nat'l. Sales Manager, N.Y.; Subject: SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENT; Effective immediately, Don Hassler, Sales Manager - Special Markets, is assuming responsibility for Syndicate Store and Accessory sales at the National level. Direct all correspondence regarding either subject to Don at the Capitol Tower, Hollywood, instead of the New York office as in the past. Don will continue to handle Rack Jobber and Foreign Language (C.O.W.) sales in addition to . . . [etc.]"

Don: Here's a picture of me on the back of Capitol News. No glasses in that shot. Nat Cole was in the picture. Somewhere I've got a picture of me and Duke Ellington.

Nori (reading caption - back cover of Capitol News): "In Stan's absence, Nat King Cole presents the Kenton awards for golfing deejays who topped the lists in the Chicago tourney. Ace club wielders are (L - R): Sid Fohrman, WIND, WGN-TV; Fred Reynolds, WGN; Ed Roberts, WGN-TV, and Don Hassler WENR.

Don: Oh really? That's when I was working in Chicago. That's when I was in charge of the record library there. That goes back to 1952.

Nori: This was in the Capitol News and that was before you worked for them.

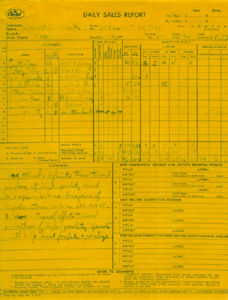

Don: Here are my sales reports . . . This is how many 45s and 78s I sold, and how many record albums, then my totals for the day and the week, plus my suggestions. This one was dated July - Dec. 1953. You can take all this, Nori. You're the keeper of the archives now.

Ed's note: Here are a couple of interesting letterheads from the Capitol Days:

This letter is from the Capitol Micro Record Mfg. Co. in Manila, Republic of the Philippines. Eusebio Contreras, manager, write to Don to tell him: "We are sorry to hear that you will be leaving the International Promotion Department . . . . At the same time, we congratulate you on your appointment as the National Sales Manager of a new aspect of Capitol operations . . ."

Another letterhead, this one from the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. Claire T. Grimes, Executive Secretary of the Chamber, write to him: "It is my pleasant duty to officially inform you that you have been elected a director of the Hollywood Tourist and Convention bureau. . . ."

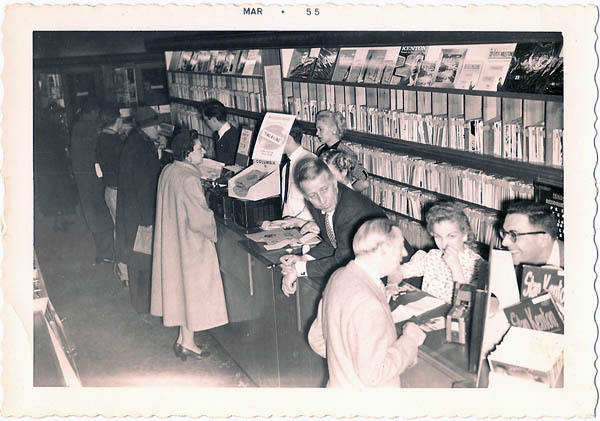

This photo was taken by Don Hassler, probably on a Kodak Instamatic. On the back he wrote:

"Stan Kenton & d.j. Jay Trompeter at record store appearance

Chicago, Ill. 1955"

Featured Link:

TransistorMuseum.com "Dedicated to Preserving the History of the Greatest Invention of the 20th Century."