This section describes my father's job at Capitol, producing the Sales Wrap-Up, the marketing department's newsletter to salesmen. My dad was fired in 1959 for suggesting that the Capitol artists play on the Playboy Jazz All-Stars Album. (Click here to see correspondence and media coverage.) After leaving Capitol, he worked for Ampex, then joined California Communications, Inc., which is where he got involved as the president of the Delta Queen Steamboat (for more info. on Bill Muster click here) - Nori

Bill Muster History

Paula: That leads up to her dad getting fired because of Playboy.

Nori: I was just going to get to that. I have the correspondence from Playboy and it seems like, just from looking at the correspondence, that my dad proposed that they advertise in Playboy and Capitol said no and then Dad told Playboy no, and then the salesman from Playboy contacted Glenn Wallichs directly in a letter. The letter starts out, "I know you like Playboy magazine and why don't you advertise with us." Like, the Playboy people went over Dad's head and approached Dad's bosses to try to talk them into it directly, and that was why the s--- hit the fan.

Don: I don't think that it was widely known, but what was widely know was that your dad had gone beyond the chain of command when he went to Playboy directly.

Nori: He wasn't in charge of placing advertising?

Don: No, he wasn't. There was another fellow who worked in the advertising department, it wasn't your dad. Your dad really didn't have anything to do with national advertising.

Nori: So my dad was just butting in because he knew Hugh Hefner?

Don: Well, yes, and that might have ruffled a lot of feathers. He was definitely out of channels when he did that. It cost him, but on the other hand it might have been a good thing because he went to Ampex and made a lot of good contacts there.

Nori: He used his contacts from Hollywood to get L.P.s put onto Ampex tape. That was their marketing plan to sell Ampex equipment.

Paula: It was the best thing that ever happened to your dad because he got with Ampex right away. We didn't suffer any financial bump because they always give you a couple months' salary and he was working for Ampex before a month was over.

Nori: Still, it wasn't fair they fired him.

Paula: The way I understand it - and I was there, I mean I was at home, but I knew. What happened I think was that the top brass told the Playboy people they couldn't afford it, or it wasn't in the budget, the usual excuse. Then your dad told the rep "because you guys are pornographic, they think you're pornographic." He piped up with the truth and the truth can get you fired.

Don: I think she's right. I think there was a reaction. It makes sense that Capitol's management might think that of Playboy. They were a pretty straight-laced bunch; Glenn Wallichs particularly, and also Lloyd Dunn, and might have ceased upon that their thought that Playboy was not a place where they wanted to spend money on advertising, because of their negative reaction to Playboy's content. The rest of us thought that was a real stuffy approach to things, and it really did have an effect on morale because everybody kinda knew that management was like that anyway.

Paula: The other thing was that your dad, Bill Muster, graduated in the same class from Illinois as Hugh Hefner and they knew each other. It was like, "Man, this hip new magazine," and the old guys at Capitol were, "Oh this is terrible. We don't want to be associated with pornography or girlie magazines." That was part of it.

Nori: When they fired my dad, did that have a ripple effect through the whole company?

Don: Well, it was a shock. Most people, me included, were kind of distressed that Capitol would be so picky as to pull a trick like that. We thought it was an example of overreacting to something that didn't call for that. I think there was some thought that your dad was a little out of line for doing what he did, but Capitol's decision to fire him was pretty much I think considered negatively by everyone that was involved, especially in the marketing department.

Nori: What exactly was my dad's job at Capitol?

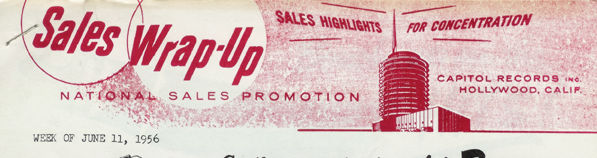

Don: Your dad was in charge of the sales newsletter that went out every week. It was called "The Weekly Wrap-Up." Bill's newsletter was the main communication of the marketing department to the salesmen and to the branches all over the country. It was a multi-page letter-size document, like a newsletter, with photos and information about new releases, and artists, and where artists were appearing and what they were doing, what Capitol's plans were for new releases of albums, and when would albums come out. Everything that involved written communication to the field came out there. Your dad's main job, I think at one time his job was to actually, physically assemble the Wrap-Up, but then he got more responsibility as time went on.

Nori: What was the name of the advertising manager?

Don: I can't remember, he reported to Bud Frazier, and the name blanks out. I know a guy named Freddie Rice had some contact there, but he wasn't the guy to make the final choice. Freddie Rice was mostly involved in merchandising, displays, graphics of various kinds, things that related to sales, but not advertising. Advertising was a separate guy. I wish I could think of his name. It might come to me.

Nori: But my dad was mostly doing that newsletter? He told me he got the job as a graphic artist, then he got in there and they realized he didn't know any graphic art.

Don: Paste-up guy.

Nori: They were going to fire him, but he said, "Yeah, but I can write!" So they transferred him to that.

Don: He can. Yeah, he wrote most of the Wrap-Up. He was supervised by a fellow named Dick Rising. Over Dick Rising was one of several sub-managers in the marketing department. Freddy Rice was another one and there were two or three others. The overall sales and marketing manager in that department was a guy named Bud Frazier. He was the key boss in there and he reported directly to the vice-president of sales and marketing. Then that was the marketing end, which was separated from sales. The sales department was basically directly responsible for getting the product into the dealers' stores. The national sales manager when I first joined the company was a fellow named Hal Cook. He was located in New York, which is kinda strange. Then there was a marketing guy there named Dick Linke, who later on became the manager of Andy Griffith and several other artists. Dick Link had a big hand in Andy Griffith's career and his name appears on all the Mayberry shows, the Andy Griffith Shows, and all the other things that Andy Griffith did. Dick Link discovered Andy Griffith, as a matter of fact, in New York.

Nori: Matlock?

Don: Matlock, he was involved in that. When Andy first got started in his career back in the early 50s, he appeared in a show on Broadway called "No Time for Sergeants." He was playing a hick character like Gomer Pile played later on, on television. "No time for Sergeants" was a stage show, but Andy Griffith made an record called "What it Was Was Football" that was a huge hit. Comedy records were big in those days. Stan Freberg was another one who did that stuff, all of them on Captitol. Anyway, Hal Cook was the national sales manager in New York for a while, then he left the company and went to Columbia. A fellow named Mike Maitland became the national sales manager in Los Angeles, or Hollywood, I should say. So Hollywood's connection to the national activities became much more solid. Mike Maitland worked right there in the tower. We all were part of sales and marketing and we all did the things necessary to get the records into dealers' stores. That was our main job.

Nori: I was going to ask you also. Didn't my dad also write the album covers?

Don: I don't know of any that he did. There was a separate department for that. That's one of the things Freddie Rice did in his department. Freddie Rice, and most of our album cover material was farmed out to outside writers; guys who were writing for magazines, newspapers, people like that, who already had some credibility and knowledge of a particular artist. For example, if you had a classical record, you'd go find a guy who was a classical critic, say for the L.A . Times. You'd say, "Here, I've got this record, this classical album of the Tchaikovsky violin concerto by so and so violinist. Can you do the liner material? The back of the L.P. record was the liner and that was where all the writing was done. Your dad, if he did any, well, he might have done it for Ampex when he worked there. They had a lot of albums they were doing and releasing, but I don't think he did anything on Capitol. Capitol kept the department lines firm.

Nori: So he just did the newsletter.

Don: He did the Weekly Wrap-Up, but he did other special projects. They shot a lot of album covers in the Capitol tower there. You probably had a couple of Christmas cards made there. I know we did.

Paula: Oh yeah, Nori with her doggie.

Don: For two or three years we could go in the Capitol photo studio and have them do photo work for us. "Government job" we called it.

Nori: Also, Dad used to bring artists home.

Don: Sure, because we were at Capitol and because we were doing sales and promotion, the artists would become familiar with some of the people in the national headquarters. We'd see them and there was a free exchange of discussions and contacts. A lot of the artists would like to do things for various employees down to a certain level. So you got a big bunny or something like that from Keely and Louie, something like that.

Paula: A white teddy bear. She used to say, "Keewee and Wooey gave it to me."

Nori: Louis Prima and Keely Smith. [click here to see some of their album covers]

Don: They had a very hot group that was playing in Vegas. They were the stars of Las Vegas for about 15 years.

Nori: I read his biography on the Internet and listened to some of his music. It was really aggressive jazz.

Don: That's right. Not exactly jazz, more like stylistic music, but he used a few style things that were very successful. They played in lounges and the people in the lounges were half drunk and they were gamblers and they would come in there and that was the only way they'd get through. We heard Keely and the Tenor Man not more than six or eight years ago. They were still doing the same thing. Louie's dead but they were still playing the same music.

Nori: You saw Keely Smith play in Las Vegas recently, right?

Don: I'll tell you why that happened [why Keely and Louie gave Nori a teddy bear]. Keely and Louie's manager was a really outgoing, very active lady named Barbara something, and that manager got the names of the key employees at Capitol and made sure that that's how those things were done. They were smart to keep the record company happy with them.

Paula: Some other artist sent a gorgeous blanket when Nori was born and it was really expensive and I didn't need blankets, so the store name was on the box, so I took it in and traded it in for a stroller. The blanket was so expensive it was the same price as a stroller.

Nori: Cool! Hey, who was that man you brought home and he started telling a story . . .

Paula: Lord Buckley. That was Jenney's friend.

Don: Lord Buckley was nowhere close to Capitol Records.

Nori: He wasn't on Capitol?

Paula: He was on dope!

Nori: He was a Frank Zappa find.

Don: Nori, there is an interesting thing for you to check out. Lord Buckley was the first - right along with Lenny Bruce - was the first jazz comic. He appeared in jazz clubs as a comic and he did all these weird, far-out things. You really - look that up on the Internet.

Nori: He was on a record Frank Zappa put together called "Zapped."

Don: Every artist I knew really dug Lord Buckley and Lord Buckley probably smoked more weed than anybody in history. He never went out on stage without being totally stoned.

Nori: Maybe Louie Armstrong outdid him.

Don: I was going to make a comment about Capitol. From the late 40s to the late 60s, Capitol Records was the most active and hot label in Hollywood.

Nori: Well, who was the president when you worked there - the U.S. president? Was that Eisenhower?

Don: Yeah, in the 50s, Eisenhower. He was elected in 52 and reelected in 56.

Nori: So he was the president the whole time you were there. I'm just trying to put it in context. Yeah, because Kennedy was elected in 60 and so he went into office in 61. Do you think that the thing with the p.r. department where they fired my dad and stuff disillusioned people. Because you said everything had changed by 61. My dad left in 59.

Don: I'm sure there was a certain amount of disillusionment. As the company aged, these things bothered people. When I left the company, I left because I realized that my management track, my advancement, probably wasn't going to go very much farther. I'd gone to a lot of seminars and I'd done my best to prepare myself to be a national sales manager or something like that, but I kept getting sidetracked into staff jobs. The money was okay, not great, but it was okay, and I was learning. But by 1961 I saw that it wasn't going to be the final culmination of my career, so I started looking elsewhere. I got this job in Santa Monica because your dad had interviewed at Transis-tronics, for this marketing managers job. Eventually he went to work at Pacific Network, but he told me about this job. He said, "I'm not going to go to work for Transis-tronics, but you might want to go out and talk to them," so I did and I got the job. I worked there for about a year and half before I went to Concord. That was a step in the right direction, from a huge company like Capitol with multiple channels of communication and so forth, I was reporting direct to the president. If I wanted to do anything sales wise, I just walked into Bernie Cirlin and said, "Why don't we do this," or "Why don't we do that," and that was it.

Nori: We moved back to L.A. in 1961. Dad was only with Ampex for about two years. While we were house hunting, we stayed in your house.

Don: He did the right thing, too, because prerecorded [reel to reel] tape was not the way people were going to go because the cassette wiped it out.

Paula: They wanted us to move to New Jersey.

Nori: Right, they wanted him to do an assessment of which would be better for them, Sunnyvale or New Jersey. He did an assessment of the housing, the distributors, the suppliers, and everything, so he said, "You want to be in New Jersey." So they said, "Okay, when are you going?" and he said, "I'm not going!"

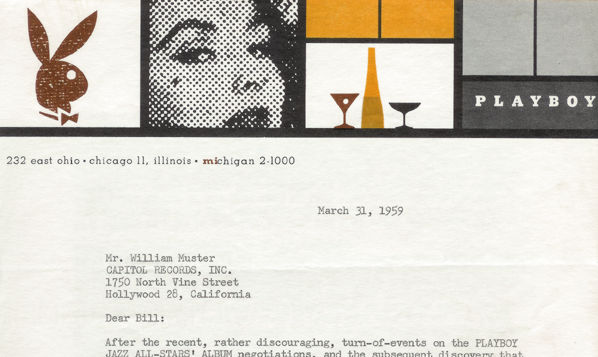

Nori (looking through Capitol files): This is the letter that the advertising guy from Playboy, the promotion director wrote to Glenn Wallichs. I guess he gave Dad a carbon copy. These are the letters he wrote to Dad.

Paula: Did he say "I'm sorry I got your ass fired"?

Nori: No! He doesn't even say that. He wrote directly to Wallichs. I want to see when Dad got fired. I have his resume here.

Paula: We asked you, "Why did your father get fired from Capitol?" and you said, "I don't know, I think it's because he didn't keep his desk clean."

Nori: I remember that. That's what I think I thought.

Don: Oh, look who wrote this, Vic Lownes. I remember him.

Nori: What does it say?

Don: Well there are two pages here Nori. Your dad's name is in that.

Nori: I know, I gotta study that. He's the one who got my dad fired.

Don: This is dated March 28, 1959.

Nori: It says here my dad worked there until May 1959.

Paula: They let him stay and send out resumes.

Nori: This is the letter that got Dad fired.

Paula: Let me read that letter from Vic Lownes. (Click here to read an excerpt from the letter. )

Nori (reading further from Capitol files): Here's an article: "Capitol Wax Axes Muster, Sherlock." Daily Variety from April 30, 1959. What date is that letter you're reading [from Victor Lownes]?

Paula: This is dated on March 28, 1959. They work fast over there.

Nori (reading): "Capitol Records is undergoing a realignment of its merchandising and sales division. In a surprise move yesterday the tower pink slipped two of its key men, Bill Muster, head of album promotion, and George Sherlock, national manager of single records. Both men said that it was probably due to the fact that they had been looking for an association elsewhere and word had gotten back to Cap. Muster had been with Capitol (continued on page 4) for five and half and a half years and was recently up to head of album promotion. Sherlock, with Cap about a year, formerly was post promo rep for Decca and was associated with the Mike Connor office prior to moving over to the tower. As of last night no replacements had been announced for Muster and Sherlock.

Paula: You know, rejection was so hard for your father because of the way he grew up [he was oprhaned in 1935 and lived in various oprhanages and foster homes until he turned 18 in 1944].

Nori: Mom has read the notorious letter and she is now going to tell us what it says. What does it say?

Paula: Well, this fellow whose name is Victor Lownes, promotion director with Playboy, wrote a letter to Glenn Wallichs on March 28, 1959, how Capitol people have assured him that Capitol is favorably disposed toward Playboy and that time will work out any problems they might have in being advertisers and/or their people mentioned, promoted in Playboy. My impression is that the letter went on for two pages, single-spaced, typewritten. The last two paragraphs Victor Lownes very subtly and left handedly infers that Bill Muster had told them some things he shouldn't have about Capitol's real [reasons for] not wanting to [advertise]. But he doesn't say anything, it's a lot of double talk and I'm sure some phone conversations went on after this letter was received.

Nori: And what was that one line, "we know that you like Playboy magazine."

Paula: Yeah, "In spite of what Bill says, we know that you really like us."

Nori: That was what got Dad fired.

Paula: Yeah, that was it. I think that this is very oblique because it's in writing. It's kind of back stabbing in a very subtle kind of way. Then they got on the phone and the guy really told what your dad said and then they said, "Okay, that's it." That's all I can get.

Nori (looking at my father's letter of reference): Wow, Dick Rising really helped my dad get another job. He must have been on my dad's side.

Paula: He was.

Don: Well, he was doing the right thing because everybody knew that the word came down from Lloyd Dunn. A lot of people didn't care for Lloyd Dunn, including me and Dick Rising and a few others.

Paula: He was an old fogey in a sea of young men.

Don: An old fogey is right. He called me on the carpet once for not having enough humility.

Paula: Humility?!

Nori: What did he want you to be humble about?

Don: He just didn't want me to be so brash and you know.

Nori: Just hitting the nail down, eh?

Paula: Well, young guys . . .

Nori: At least they didn't make you bow down. In ISKCON if you did something wrong you were supposed to bow down to the person and apologize.

Don: Lloyd Dunn also didn't like pipe-smokers or crew cuts.

Paula: Yep.

Nori: What's wrong with a crew cut?

Paula: In those days it meant the young guys going off the beaten track. The butch cut was a thing for young guys. It was anti-establishment.

Nori (pulling a letter from the files): This is a letter from Dad to Victor Lownes, dated April 30: "Starting immediately how about sending my complimentary copy of Playboy to my home."

Paula: They did, too.

Nori (continuing): "You see, if you send it to Capitol it will probably never get to me as I am not working there anymore. As you may suspect, I was asked to leave. If Playboy ever goes into the recording business you may find me useful so I have enclosed my resume."

Don: Good for him.

Nori (concluding): "By the way, I thought the May issue was a complete gas. Regards, Bill Muster."

Paula: Whoa, nothing shy about him.

Don: Your dad stuck his neck out very far on that.

Paula: Yep.

Nori: He should have seen what a snake this Victor guy was.

Paula: Yep.

Don: Well, the Victor guy was thinking overall about business from Capitol, not so much about individuals.

Paula: Yep.

Nori: He got my dad fired.

Paula: Your dad was just not a high up person [who could have influenced the management to advertise with Playboy]. He was one of the staff, but he wasn't any big boss.

Don: You know, I'll be that's what really caused me to start looking. I figured if it could happen to Bill, it could happen to any of us.

Paula: And you were already accused of not being humble.

Don: Well, shucks, everybody else was too, for that matter. That was a wake up call because we all worked together in that merchandising department and we were all extremely close friends. It was really the shits if one guy gets fired, especially for a stupid thing like that. Most companies that just wouldn't happen.

Nori: Here's another article from Variety. This one is dated May 6, 1959: It says, "Muster, Sherlock Fired by Capitol; More on Way? Hollywood, May 5. A revamp of its merchandising and sales division is underway at Capitol Records. The tower, in a surprise move . . ." oh, this is the same article [just a new headline].

Paula: They say "the tower" like they say "the White House."

Don: Well it was called the tower, it was the Capitol Tower, it was The Tower. If you were on the thirteenth floor, you were it. That was the executive floor.

Nori: Listen to this, "Although the tower is trying to keep the shuffling and dismissals under wraps, it's understood that other key men will be bounced in the future."

Don: I'm sure the phrase "other key men" made the rest of us go "Holy sit! Who's next? How am I going to pay my mortgage then?"

Paula: That's terrible on morale to do that for such a dumb thing.

Nori (continuing): "Both men said that it was probably due to the fact that they had been looking for an association elsewhere and word had gotten back to Cap." That wasn't true.

Paula: No. I know Bill wasn't looking anywhere because he liked being there. The stardom rubbed off on you. Bumping elbows with Sintra. He felt he was going to rise in the company over the years.

Don: Neither Bill nor I were ever humble enough to rise in that company.

Paula: Not with that management.

Don: He had it forced on him and I was able to make the jump before [long].

Nori: Here's the Sales Wrap-Up.

Don: The National Sales Promotion. That's it! That's what it looked like!

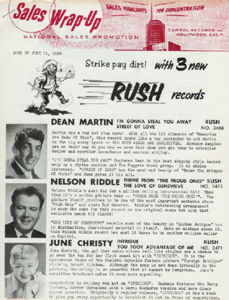

The Sales Wrap-Up and detail. Below: a page from the Wrap-up.

Paula: Did they print it up?

Don: Yes, remember that salesman from the printer who had the sail boat? That's who printed it.

Paula: Yeah, Art . . .

Don: Yeah, they would show up at the last minute and he'd have to print them and they would have changes. Oh man.

Paula: In those days they didn't have computers and things, and they had to pick those little things up.

Nori: Yeah, hot type.

Paula: What was Art's last name.

Don: Walker.

Paula: He was a very sweet man.

An order form postcard.

Click here for more about Playboy Magazine.

This letter from Victor Lownes to my father said, in part: "I certainly hope that I have not, in any way, put you on the spot, and will feel just dreadful if I later discover otherwise," and "enclosed is a copy of my letter to him [Wallichs] subsequent to our phone conversation . . ."

The notorious letter, dated March 28, 1959, said of my father: "Incidentally, I would not have mentioned the correspondence and obvious enthusiasm for Playboy expressed by Bill Muster if you had not made it quite clear that you are not really personally unfavorably disposed towards Playboy. I certainly would not want to place Bill on the spot, and trust that I haven't. He has simply tried right along to indicate that Capitol, as a company, is friendly toward Playboy and that everything would work out in time. I am sure he did this because he sincerely believes in our ability to move records. Although I have assured him that our editorial integrity would always guarantee Capitol fair treatment no matter what kind of attitude might be manifest toward us by the company."

That alone might not have gotten my father fired. However, they saw my father as an agitator, stepping out of line, and it led to this perceived embarrassment:

"I know that the next Playboy Jazz All-Stars Album will truly be complete for the first time, as I know that the [Capitol] artists do want to be included . . . Since our conversation I have talked to Stan Kenton, who is appearing here in Chicago, and he was extremely enthusiastic about obtaining clearance to appear . . . He was pleased to learn that I had talked directly to you and indicated that he would call you to reconfirm that he wants to exercise the option to participate if you will permit."

When it was happening and we were moving to Sunnyvale, I thought my father was fired because he didn't keep his desk clean. I was only three years old. Later, after moving back to L.A., at about seven years old, I asked my mom why we got Playboy magazine. She said that we had a lifetime free subscription because they got my father fired from Capitol. Throughout my childhood whenever we drove down the Hollywood freeway, my brother and I would point enthusiastically to the Capitol tower and chime in, "That's where Daddy got fired from!" He shouldn't have gotten involved in Playboy's dilemma, but he did. It doesn't bother me now, because it's been so long it's like a part of history, but it was a fateful turn of events for my father and our family. We never would have gotten to live in an Eichler in Sunnyvale* if we'd stayed in Dixie Canyon. After Ampex, my father went on to work for Pacific Network and the Delta Queen. He wrote the Traveler's Almanac, published by Rand McNally, and ultimately opened the first video post-production studio in Hollywood, California Communications, Inc. In the end it all worked out okay. I'm interested to hear from anyone who might remember the old Capitol Days, so please write to me (contact info.). That includes relatives and old family friends from those years! - Nori

Bill Muster at Wikipedia.org

Capitol Records Index